Granites and valuable minerals

The granites of Southwest England are an important later feature of the Variscan mountain belt. Granites are igneous rocks with coarse (millimetre across) crystals that have grown, interlocking with each other, as the molten material cooled slowly and solidified at some depth in the Earth’s crust. The minerals of the granite are most commonly quartz (typically about 30 per cent) and feldspar, generally with some other minerals such as mica (Fig. 43). The granite liquid (often called magma) formed as a result of melting deep within the outer layers of the Earth and was then forced upwards, sometimes pushing aside the overlying bedrock and sometimes replacing it by melting. The granites solidified at depths of several hundred metres or more below the surface and are now at, or near, the surface because of landscape erosion. The main granite areas include the Isles of Scilly in the west, followed by Land’s End, Carnmenellis, St Austell, Bodmin Moor and Dartmoor in succession to the east. These distinct granite areas at the surface can be visualised as the tops of fingers extending upwards from a single continuous granite body detectable by gravity surveys at greater depth under the spine of Southwest England (Fig. 44). The deep body extends for some 200 km along the length of the mountain belt.

FIG 43.Polished slab cut in the Dartmoor granite showing typical granite texture. Crystals of quartz (light grey), feldspar (white) and biotite (black) have interlocked as the magma (molten rock) solidified on cooling. (Copyright Landform Slides – Ken Gardner)

FIG 44.Diagram showing the large granite body below the bedrock of Cornwall and Devon, and the way the granite bosses now visible at the surface are upward extensions of this larger body.

Although there was probably some time range in the arrival of different granite bodies in the upper crust, the main episodes took place at the very end of the Carboniferous and during the earliest Permian, roughly 300 million years ago.

The arrival of the granites from below was only one part of the invasion of the upper levels of the bedrock that took place at this time. Widespread mineralisation around the granites has probably been even more important than the arrival of the granites themselves, in terms of human history. The term mineralisation is used to cover the alteration of the solid granite and the surrounding (older) bedrock that has, in some areas, been caused by the movement of very hot and chemically rich water, using the network of cavities and fractures that existed in the rocks. Because of the chemistry of the rocks deep down, many different chemical elements were brought to the upper levels and crystallized there to form new and valuable minerals, or caused alterations of the earlier solid rocks.

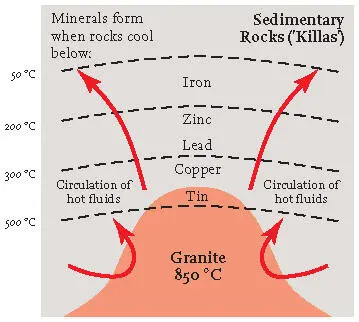

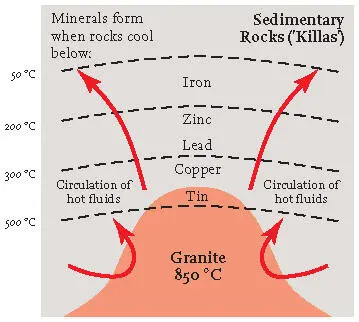

FIG 45.Simple diagram of a slice through the Earth’s upper levels, showing how the temperature patterns around a granite body have been responsible for the distribution of minerals containing the more important chemical elements.

The granites probably solidified in the Earth at temperatures of about 850 °C, and most of the mineralisation happened at rather lower temperatures as the rocks cooled (Fig. 45). Tin, wolfram, arsenic and copper minerals formed at between 500 and 300 °C, whereas silver, lead, zinc, uranium, nickel and cobalt minerals formed at between 300 and 200 °C, and iron minerals between 200 and 50 °C.

The tin of Cornwall was a major reason why some of the early inhabitants of mainland Europe were interested in Britain. In fact there is evidence that tin minerals were being gathered here more than 3,000 years ago, during the Bronze Age. In those days, much of the material was collected from young sands and gravels derived from the weathering and erosion of the mineral-bearing rock, unlike later times when mining techniques were developed to extract tin directly from the bedrock.

Some granite areas contain much more mineralisation than others, and the range of minerals and chemical elements that are present varies greatly. This depends on the temperature of the granite emplacement and the chemistry of the fluids accompanying and following the granite. The Land’s End and Carnmenellis granites are particularly rich in tin, and it is around these granites, in areas near to St Ives, Camborne, Redruth and Helston, that most of the mining has been concentrated. The remains of this mining are often clear to see (Fig. 46), but the presence of the minerals themselves does not generally influence the natural scenery.

FIG 46.Tin mine workings near Cape Cornwall, west Cornwall. (Copyright Dae Sasitorn & Adrian Warren/www.lastrefuge.co.uk)

In some of the granites, hot fluids from below altered the mineral feldspar (one of the dominant granite minerals) and turned it into the soft clay mineral kaolinite. The china clay industry has developed round the presence of this mineral, which has usually been extracted from the altered granite by washing it out with powerful water jets. This process has changed the scenery dramatically, particularly around the St Austell granite. For every tonne of useable kaolin, 5 tonnes of waste granite material are produced, and heaps of this waste are obvious scenic features in these areas (Fig. 47). The famous Eden Project at Bodelva, near St Austell, has been constructed inside a large former china clay quarry.

FIG 47.China clay excavations at St Austell. (Copyright Dae Sasitorn & Adrian Warren/www.lastrefuge.co.uk)

The older rocks surrounding each of the granite intrusions generally show evidence of alteration that occurred as the mobile granite worked its way upwards from below. This contact metamorphism , often accompanied by the growth of new minerals, is the result of the transfer of heat and introduction of new chemical components from the granite. It has usually resulted in making the rocks more resistant to later erosion at the surface.

Younger episodes

Sedimentary markers

Between 7 and 20 km to the southwest of Exeter, traversed by the A38 and A380 trunk roads, the Great and Little Haldon Hills are capped by a layer of sediments, assigned to the Upper Greensand, and spanning in age the Early/Late Cretaceous boundary (between about 105 and 95 million years ago). These are the westernmost erosional relicts of a continuous sheet of sediment of this age that extended across much of the rest of Southern England. In the Haldon Hills area, the sandy and fossiliferous material seems to have formed near the coastal margin of an extensive Cretaceous sea.

The Haldon Gravels are distinctive deposits that occur above these Cretaceous sediments. They consist largely of flint pebbles and contain sand and mud between the pebbles. Some of the gravels appear to be the result of removal by solution of the calcareous Late Cretaceous Chalk that can no longer be found in its unaltered state so far west. The flint nodules in the Chalk were then left as a layer of much less soluble pebbles. Some of the gravel appears to have been carried to its present position by rivers or the sea, perhaps also with the incorporation of kaolinite clay from the Dartmoor granite. The age of these gravels appears to be early Tertiary, perhaps about 55 million years.

A few kilometres west of the Haldon Hills, northwest of Torquay, the Bovey Formation of early Tertiary age (Eocene and Oligocene, about 45 to 30 million years ago) occurs in a distinct, fault-bounded basin. The formation is more than 1 km in thickness and consists primarily of the clay mineral kaolinite, deposited as mud by local streams, and associated with minor amounts of sand, gravel and peat-like organic deposits of lignite. This sediment fill continues to be a very important material for ceramics, pipes, tiles etc. ranging from high-quality china clay to lower-quality materials. Most of the sediment appears to have been carried into the basin from the area of the Dartmoor granite and its surroundings. The Bovey Basin formed as a result of subsidence along the northwest-to-southeast trending Sticklepath Fault Zone (Fig. 39) which cuts across the whole of the Southwest Region. This fault zone seems to have been active during the accumulation of sediment in the basin and so, at least in this phase of its history, it was much younger than the Variscan structures of the Southwest generally. Further to the northwest along the same fault zone is the smaller Petrockstowe Basin near Great Torrington (see Fig. 38), and, offshore, under the Bristol Channel is the larger Stabley Bank Basin, east of Lundy Island.

Читать дальше