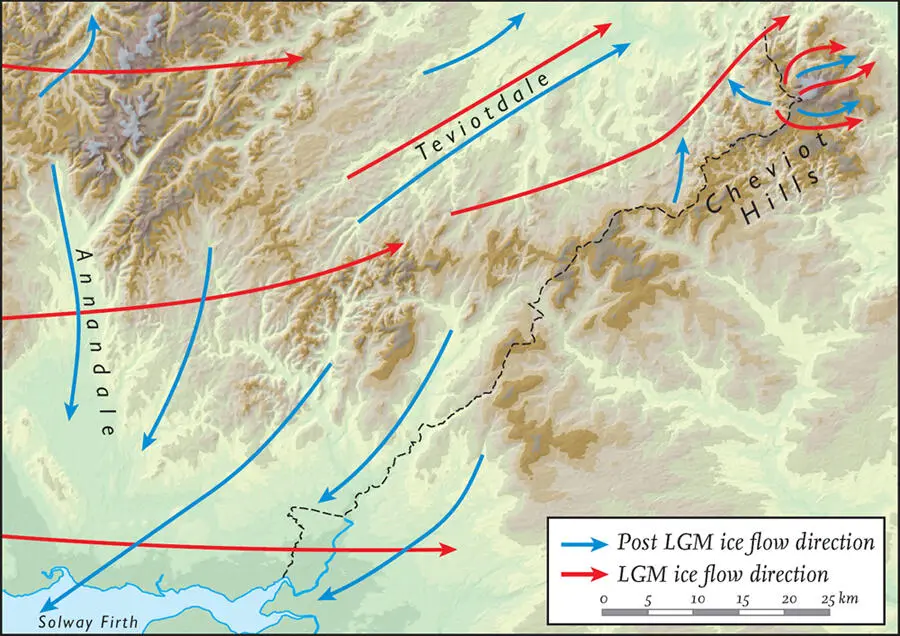

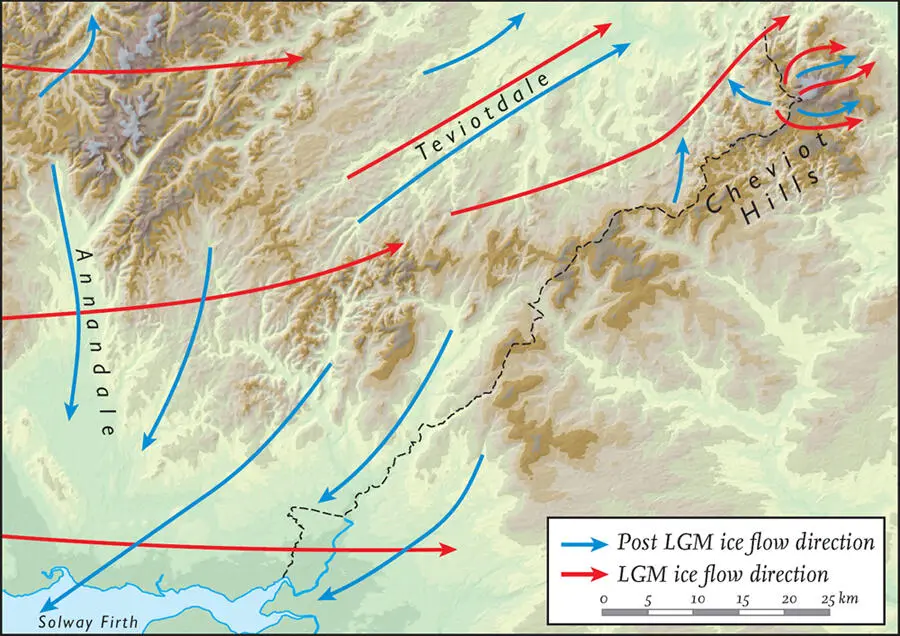

As mentioned above, the Cheviot Hills acted as a small but independent centre of ice accumulation and glacier dispersion during the Devensian glaciation. During this time, Cheviot ice flowed radially outwards from the centre, shielding the higher parts of the massif, particularly those above about 300 m, from the ice from the Solway Firth and Tweed basins. The lower peripheral hills, meanwhile, were overwhelmed and smoothed by this ice, and blocks of bedrock from the Tweed and Solway areas were deposited by the ice up to altitudes of around 300 m. Above this level in the central parts of the massif, soft, deeply rotten bedrock is relatively common and there are tors, erosional relics, over the border in England. These areas have clearly been glaciated, as they are often overlain by till, and yet they have survived erosion. Perhaps at the centre of Cheviot ice dispersal, the preservation favoured net deposition rather than erosion.

FIG 62. Ice flow in Area 2 at different times during the Devensian (LGM is Late Glacial Maximum).

The brief return to glacial conditions which occurred during the Loch Lomond Stadial (around 13,000 to 11,500 years ago; see Fig. 39) had only a limited effect in this Area. Glaciers returned only to the highest ground, such as around Broad Law, but even here the largest was only a few kilometres long. The position of these glaciers is clearly represented by terminal moraines – ridges of glacial till bulldozed by the Loch Lomond Stadial glaciers. Good examples are found, for example, at Loch Skene ( Fig. 63), where a series of terminal moraines records fluctuations in glacier growth during retreat. The terminus of one ice lobe from this time has been located at the head of the Grey Mare’s Tail waterfall, at an altitude of around 450 m. Another terminal moraine forms a prominent ridge some 250 m long that runs parallel to the northeastern side of the loch (‘the Causey’). Indeed, Loch Skene owes its presence to these moraines, which effectively dam the loch outlet.

Glacial modification of the uplands

Glacial erosion has played an important role in creating the final shape of the landscape. Most of Area 2 was extensively ice-scoured throughout the course of the Quaternary glaciations, and the land surface present at the end of the Tertiary became heavily modified. In the uplands, moving ice lowered the valley bottoms and smoothed the mountains, creating the high broad hills seen today. This erosion was not as intense as that to which the western Southern Uplands were subjected, and whilst the main valleys were deepened by powerful ice streams, the intervening ridges and plateaus escaped deep scouring. In general, the uplands of this Area therefore lack the ‘Alpine’ form seen in the Highlands of Scotland: corries, arêtes and troughs are not as common nor, when present, as pronounced ( Fig. 63

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.