In fact, we only know of Shakespeare’s work because two of his friends had the foresight to collect his plays together following his death and have them printed. The only reason they did so was apparently because they rated his talent and thought it would be a shame if his words were lost.

Consequently his body of work has ever since been assessed and reassessed as the greatest contribution to English literature. That is despite the fact that we know that different printers took it upon themselves to heavily edit the material they worked from. We also know that Elizabethan plays were worked and reworked frequently, so that they evolved over time until they were honed to perfection, which means that many different hands played their part in the active writing process. It would therefore be fair to say that any play attributed to Shakespeare is unlikely to contain a great deal of original input. Even the plots were based on well known historical events, so it would be hard to know what fragments of any Shakespeare play came from that single mind.

One might draw a comparison with the Christian bible, which remains such a compelling read because it came from the collaboration of many contributors and translators over centuries, who each adjusted the stories until they could no longer be improved. As virtually nothing is known of Shakespeare’s life and even less about his method of working, we shall never know the truth about his plays. They certainly contain some very elegant phrasing, clever plot devices and plenty of words never before seen in print, but as to whether Shakespeare invented them from a unique imagination or whether he simply took them from others around him is anyone’s guess.

The best bet seems to be that Shakespeare probably took the lead role in devising the original drafts of the plays, but was open to collaboration from any source when it came to developing them into workable scripts for effective performances. He would have had to work closely with his fellow actors in rehearsals, thereby finding out where to edit, abridge, alter, reword and so on.

In turn, similar adjustments would have occurred in his absence, so that definitive versions of his plays never really existed. In effect Shakespeare was only responsible for providing the framework of plays, upon which others took liberties over time. This wasn’t helped by the fact that the English language itself was not definitive at that time either. The consequence was that people took it upon themselves to spell words however they pleased or to completely change words and phrasing to suit their own preferences.

It is easy to see then, that Shakespeare’s plays were always going to have lives of their own, mutating and distorting in detail like Chinese whispers. The culture of creative preservation was simply not established in Elizabethan England. Creative ownership of Shakespeare’s plays was lost to him as soon as he released them into the consciousness of others. They saw nothing wrong with taking his ideas and running with them, because no one had ever suggested that one shouldn’t, and Shakespeare probably regarded his work in the same way. His plays weren’t sacrosanct works of art, they were templates for theatre folk to make their livings from, so they had every right to mould them into productions that drew in the crowds as effectively as possible. Shakespeare was like the helmsman of a sailing ship, steering the vessel but wholly reliant on the team work of his crew to arrive at the desired destination.

It seems that Shakespeare certainly had a natural gift, but the genius of his plays may be attributable to the collective efforts of Shakespeare and others. It is a rather satisfying notion to think that his plays might actually be the creative outpourings of the Elizabethan milieu in which Shakespeare immersed himself. That makes them important social documents as well as seminal works of the English language.

Money in Shakespeare’s Day

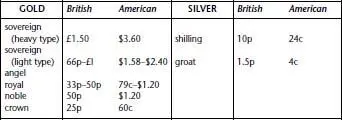

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to relate the value of money in our time to its value in another age and to compare prices of commodities today and in the past. Many items are simply not comparable on grounds of quality or serviceability.

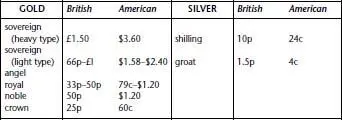

There was a bewildering variety of coins in use in Elizabethan England. As nearly all English and European coins were gold or silver, they had intrinsic value apart from their official value. This meant that foreign coins circulated freely in England and were officially recognized, for example the French crown (écu) worth about 30p (72 cents), and the Spanish ducat worth about 33p (79 cents). The following table shows some of the coins mentioned by Shakespeare and their relation to one another.

A comparison of the following prices in Shakespeare’s time with the prices of the same items today will give some idea of the change in the value of money.

As a budding playwright, Shakespeare was attacked by an older writer, Robert Greene, for plagiarism: ‘an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers’. Towards the end of his career, for his next-to-last play to be completed, Shakespeare drew upon a story by this same Greene, and so created The Winter’s Tale .

In Shakespeare’s own period, older playgoers, remembering Greene and seeing this work for the first time, must have thought they knew how it ended. The king, consumed by jealousy, repudiates his queen, who dies. He soon after recognises his error, but it is too late. That, at least, is the story of Greene’s Pandosto . Shakespeare, however, picks up this simple tale and turns it into a myth of resurrection. We all, like the early playgoers, think Hermione to be dead. We see her fall, deadly sick, on stage. News of her death is brought by Paulina, whom we know to be a reliable witness. Sixteen years pass, without any sign of her.

Tragedy lies very close to comedy here. The earlier episodes, the autumn and winter parts of the play, display the imagery of disease and dearth: ‘Why then the world and all that’s in’t is nothing;/The covering sky is nothing; Bohemia nothing;/my wife is nothing; nor nothing have those nothings,/If this be nothing’. But those corrugated rhythms give way to the comedy of Autolycus and his song of spring: ‘When daffodils begin to peer,/With heigh! the doxy over the dale’. There is the daughter who was thought lost, Perdita in her harvest scene, also evoking the spring: ‘daffodils,/That come before the swallow dares, and take/The winds of March with beauty’. This prefigures the restoration of Hermione, which is the key to the play.

The meeting of Perdita with Leontes, her father, which could have been one of Shakespeare’s reconciliation set-pieces, is reported at second hand in order to preserve the grand climax for the restitution of Hermione. There, at the end, is the Statue Scene when Hermione rises, as though from the dead, and joins her repentant husband.

So far from attempting to seem naturalistic, the text drives home the impossibilities: ‘That she is living,/Were it but told you, should be hooted at/Like an old tale’. But Shakespeare has paid the ‘old tale’ of his former enemy, Robert Greene, the supreme compliment of turning it into high drama. Leontes says, ‘I saw her,/As I thought, dead; and have, in vain, said many/A prayer upon her grave’. However, the prayers have not been in vain. The whole scene is an acting out of resurrection.

The extravagance of the plot is matched by that of the structure. Such critics as the Italian, Castelvetro, and the Englishman, Sir Philip Sidney, thought that the Greek philosopher, Aristotle, had imposed rules on the drama that decreed restrictions as to the time a play should encompass in its action, the place – only one – it should represent, and the plot – very simple – that it should deploy. These rules were called ‘unities’, and Shakespeare violated these unities in an exuberant fashion. The action covers sixteen years, and not smoothly: there is a gaping void between Act 3 and Act 4. The scenes swerve between Sicily, the kingdom of Leontes, and Bohemia, the kingdom of his supposed rival, Polixenes. The plot, as we have seen, is far-fetched beyond all decorum. However, the appeal is not to the intricacies of art, but to nature. In the end, what we are shown is nature’s own cycle, represented in the death and restoration of Hermione. She is a kind of earth goddess. We see the earth die, every winter. Yet it revives in the spring. It is an idea similar to that of Jesus’ parable of the Prodigal Son. He ‘was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found’ (Luke 15:24).

Читать дальше