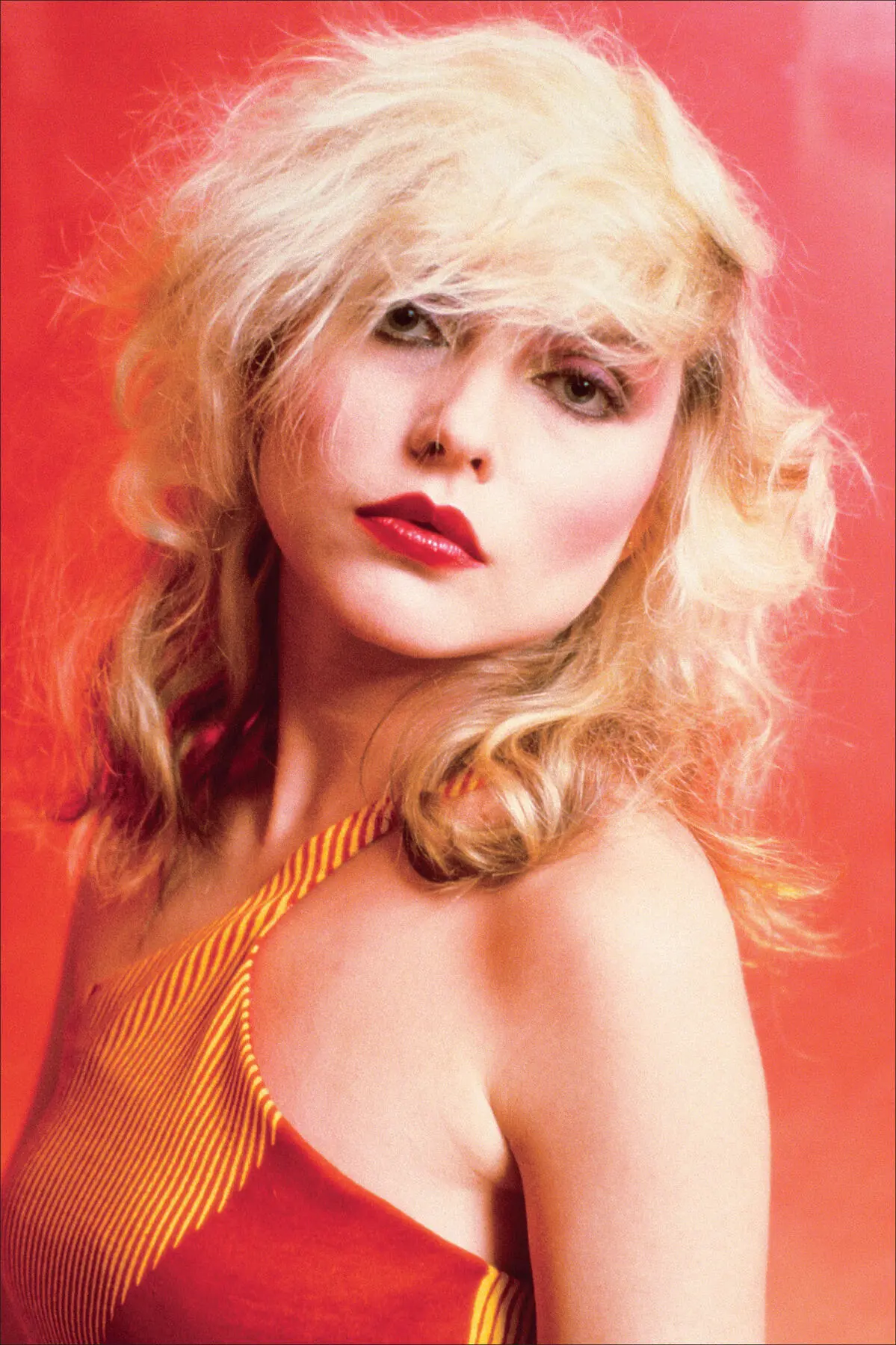

House Lights

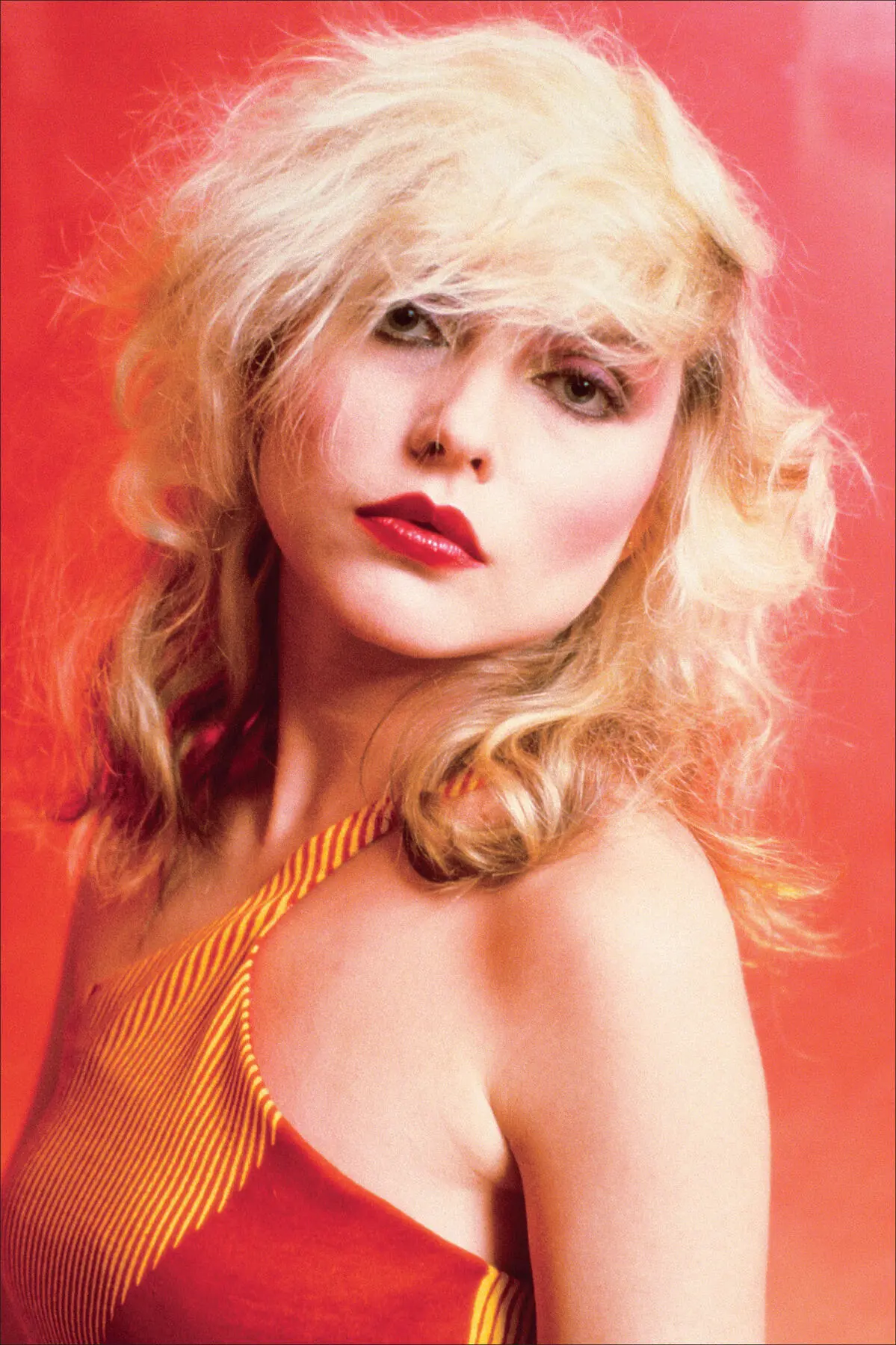

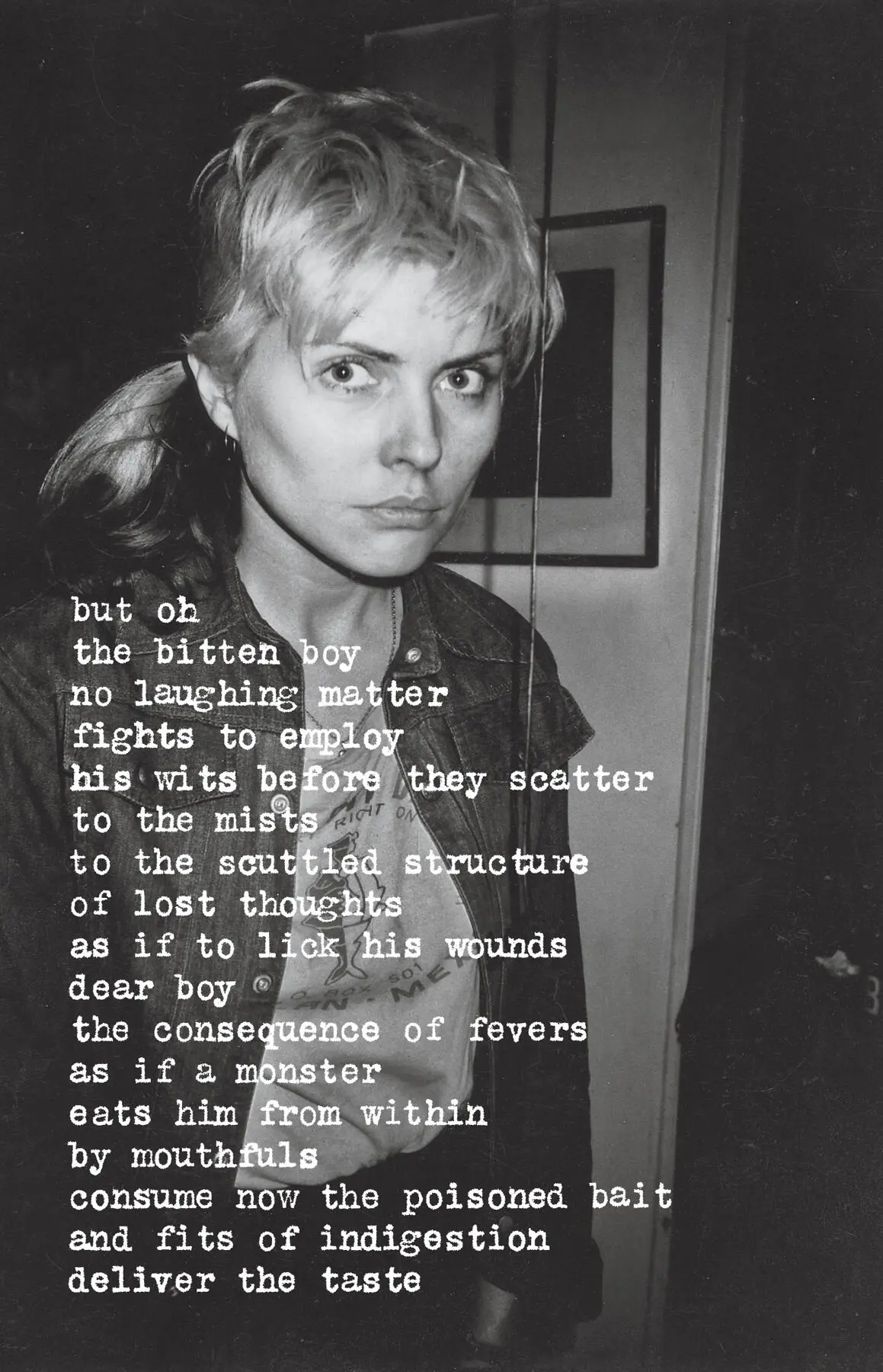

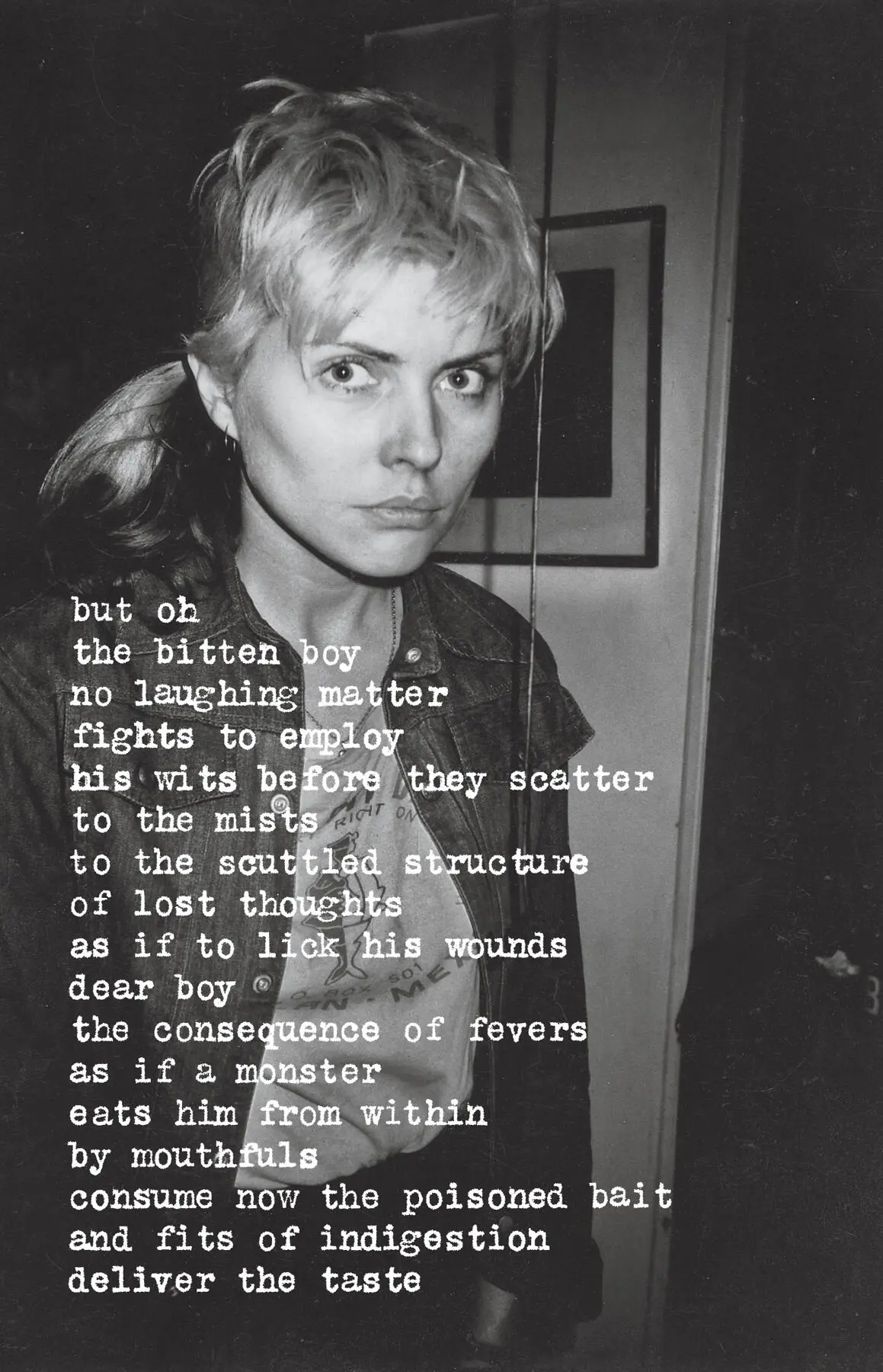

Mick Rock, 1978.

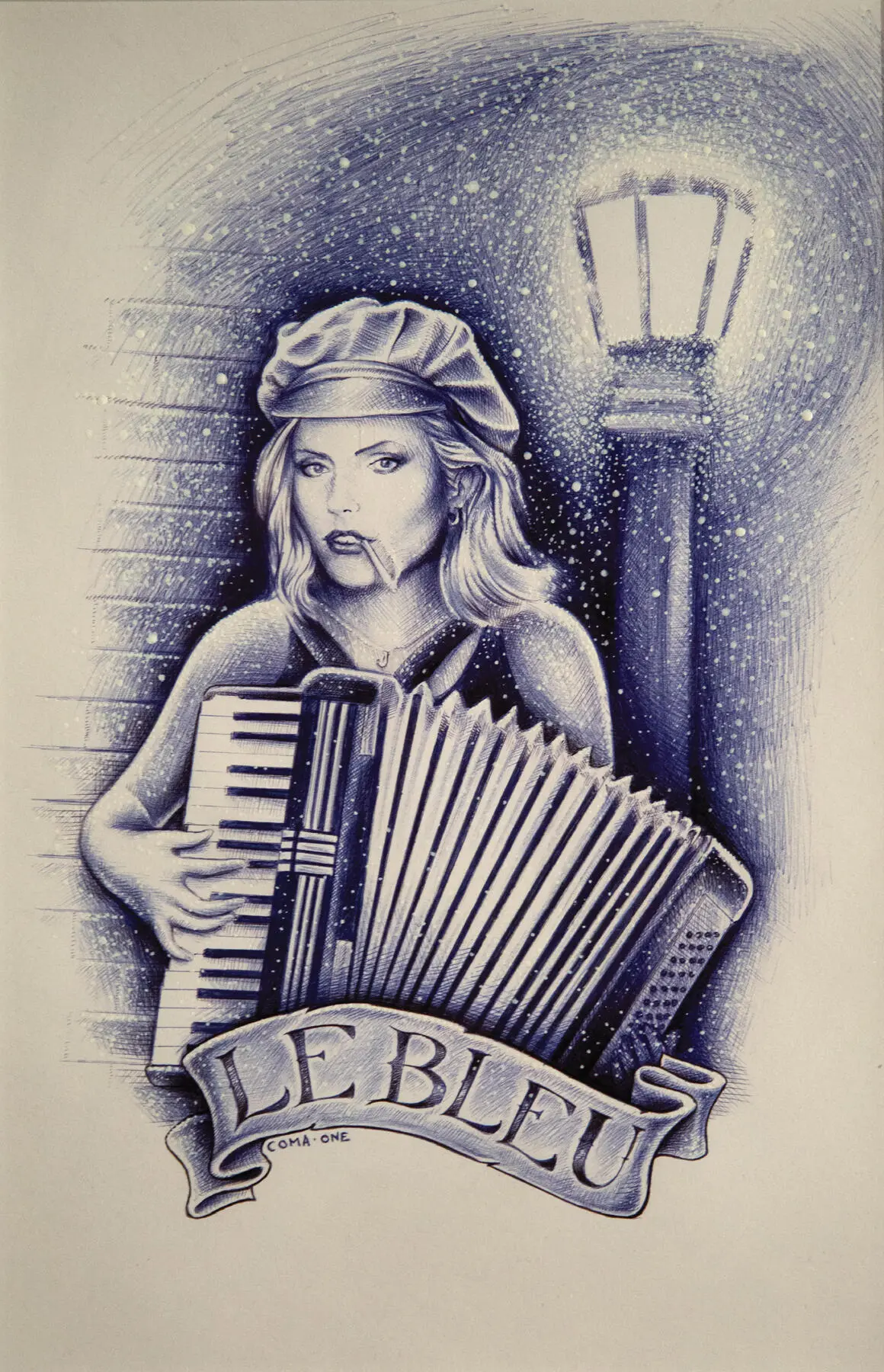

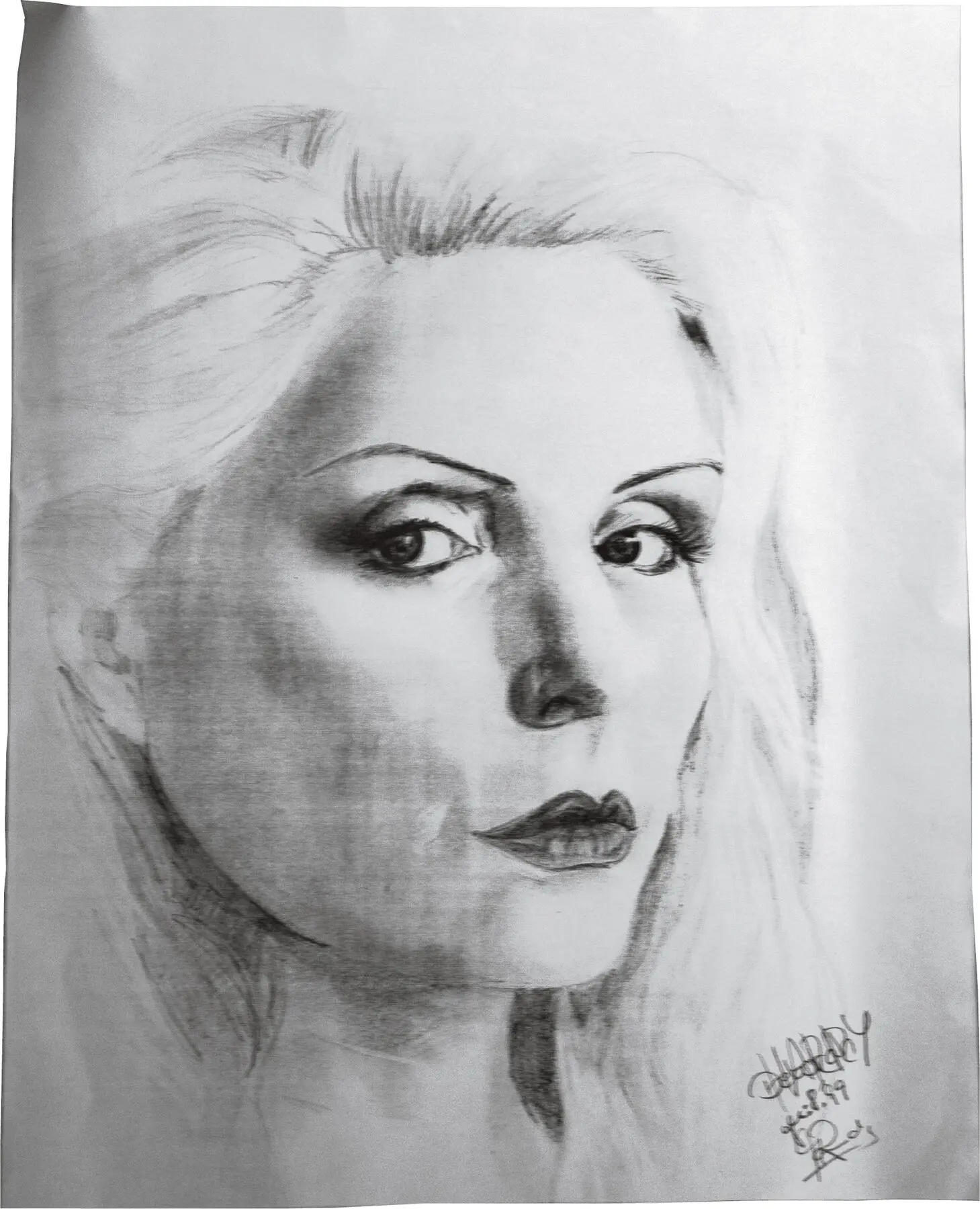

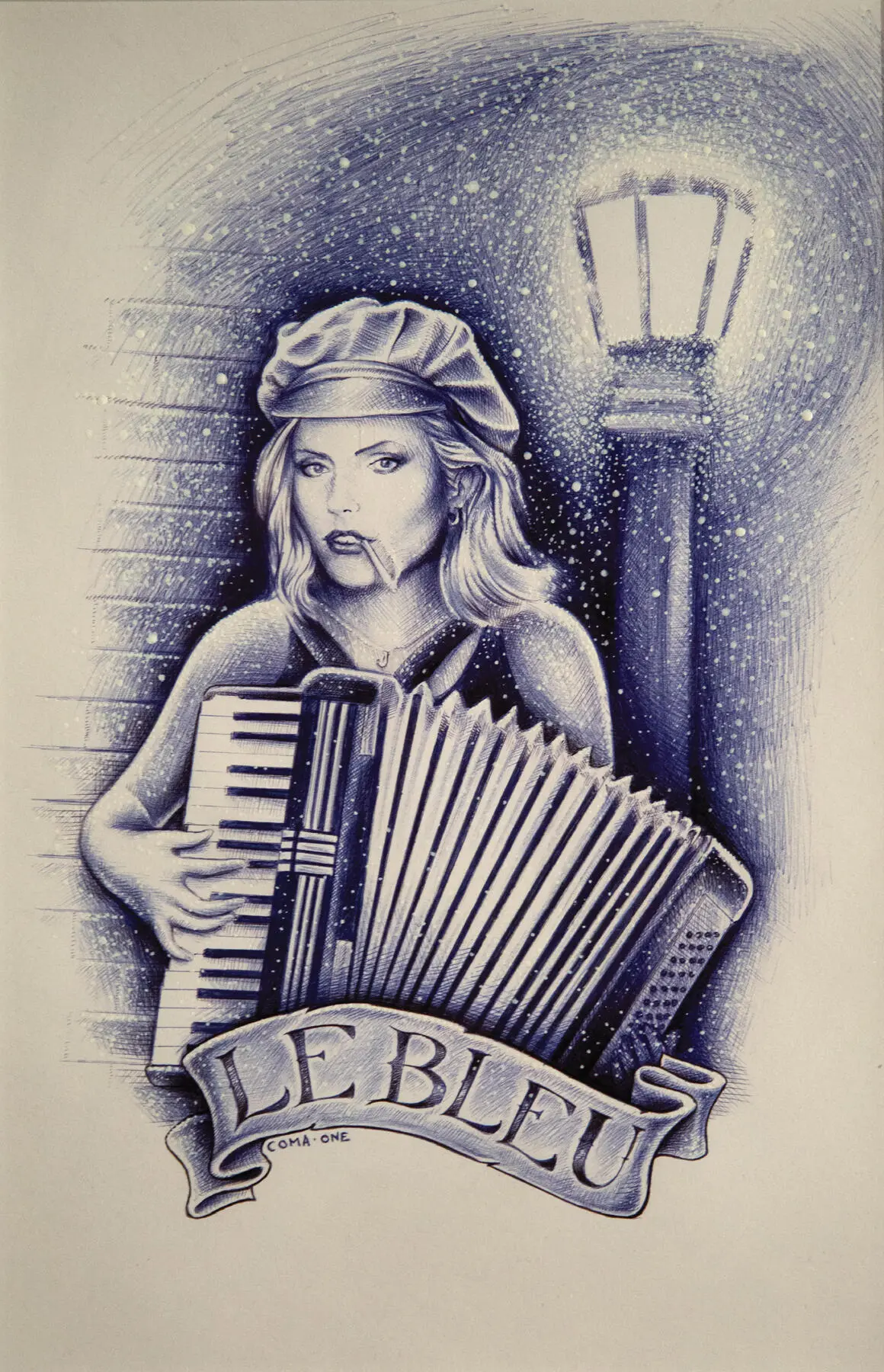

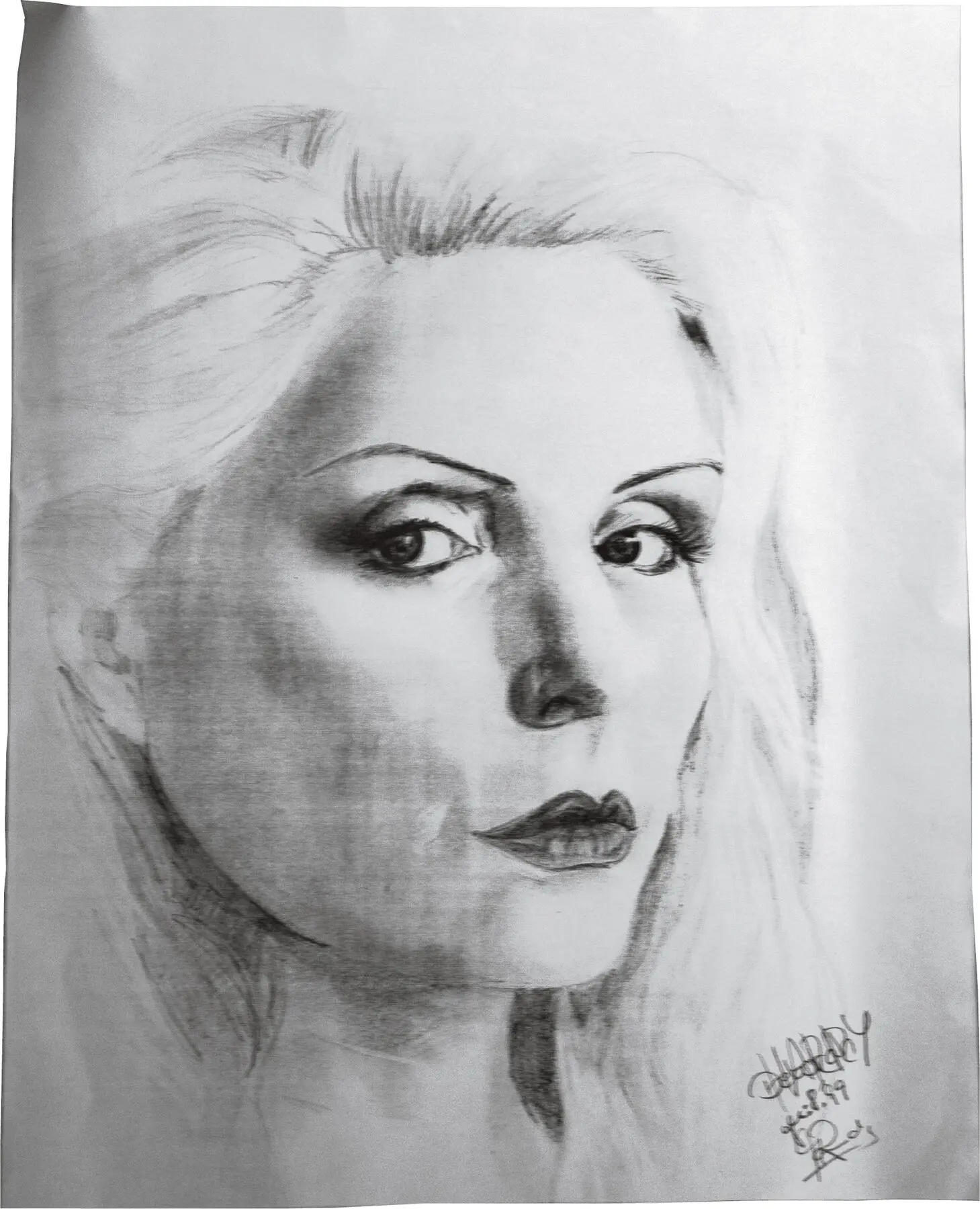

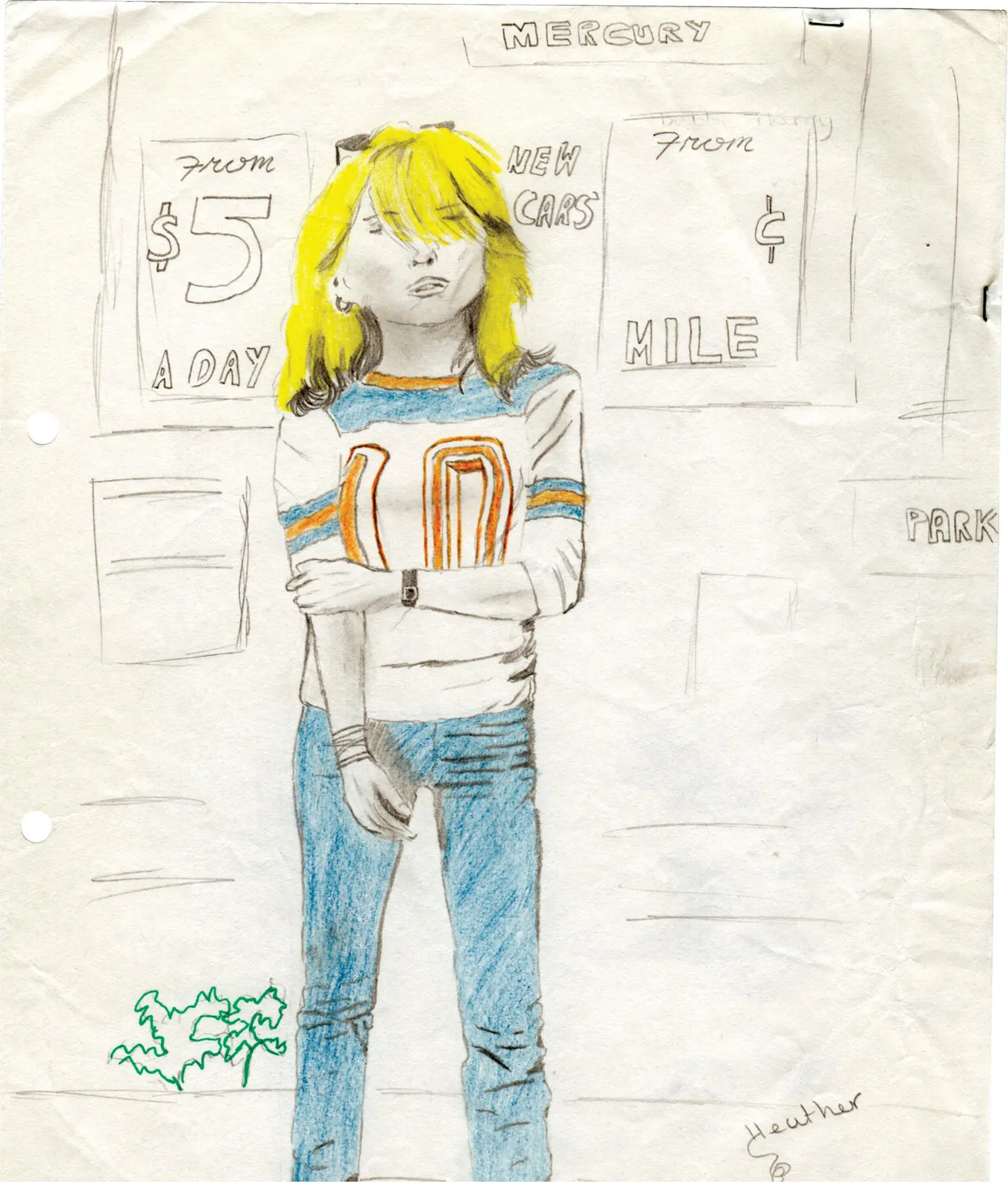

AFTER ROB ROTH HAD SENT ME ALL THE SCANS OF MY FAN ART collection, he drove off back to NYC in his white pickup truck. Rather him than me that day—I’d been tiring of my constant commutes to the city. We had been working on how best to reproduce and organize the drawings and paintings I’ve accumulated over all the years, while being Blondie or being in Blondie. I didn’t have a strong reason to save everything, but I couldn’t just abandon them. Mostly, I kept them all because I just like them. The sweet and insightful drawings, paintings, mosaics, dolls, and hand-drawn T-shirts (of which only one remains) have traveled with me on tours around the world, suffering flight delays and bad weather and surviving just like me, a bit frayed at the edges, but still intact.

I’ve moved about ten or eleven times over the years and am amazed that I’ve managed to hold on to my fan art collection for all that time. For a while, my files were stored in Chris’s basement studio down in Tribeca where they managed to survive a major flood of the Hudson River, followed by the destruction of the Twin Towers, which were only two blocks away. Now that I’ve written a memoir starting with my childhood, progressing through the years of Blondie almost to the present, I’m even more amazed.

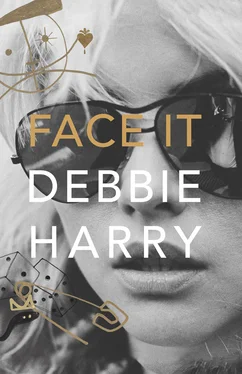

I know some of the artwork is MIA and I’m hoping that more of it will emerge as I go through rediscovered boxes and files and whatever. My methods of preservation were at times pretty much catch-as-catch-can, so things turn up in unexpected places, like a series of surprise parties—which are always good for a little laugh. For many years I didn’t travel with a road or wardrobe case, which in later years has been the most useful way to keep these artifacts intact and safe. Sometimes I even wondered why I was doing what I was doing except that I just did it. Now the fan art collection is giving an added meaning to the title of my book, Face It . . .

4

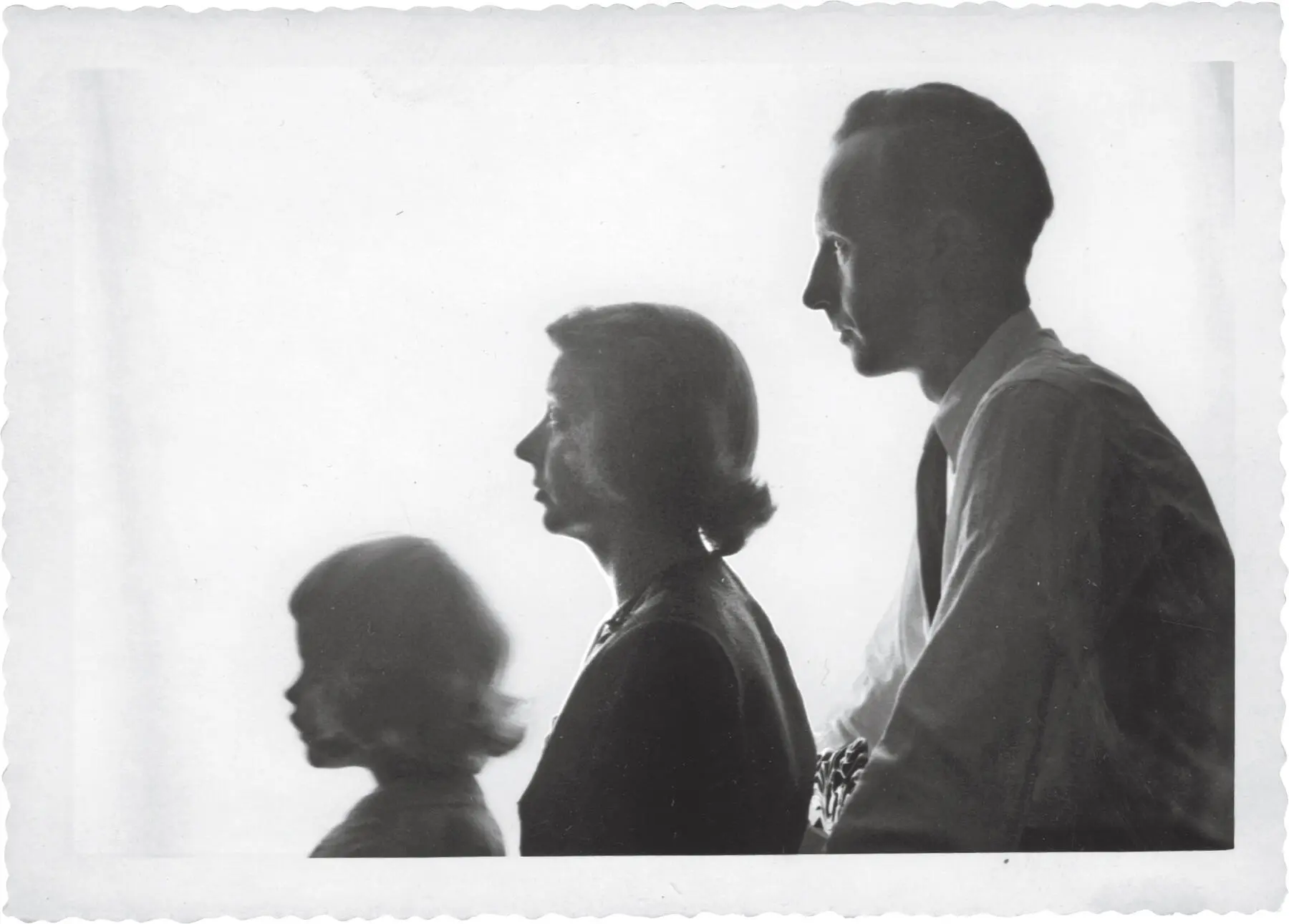

Singing to a Silhouette

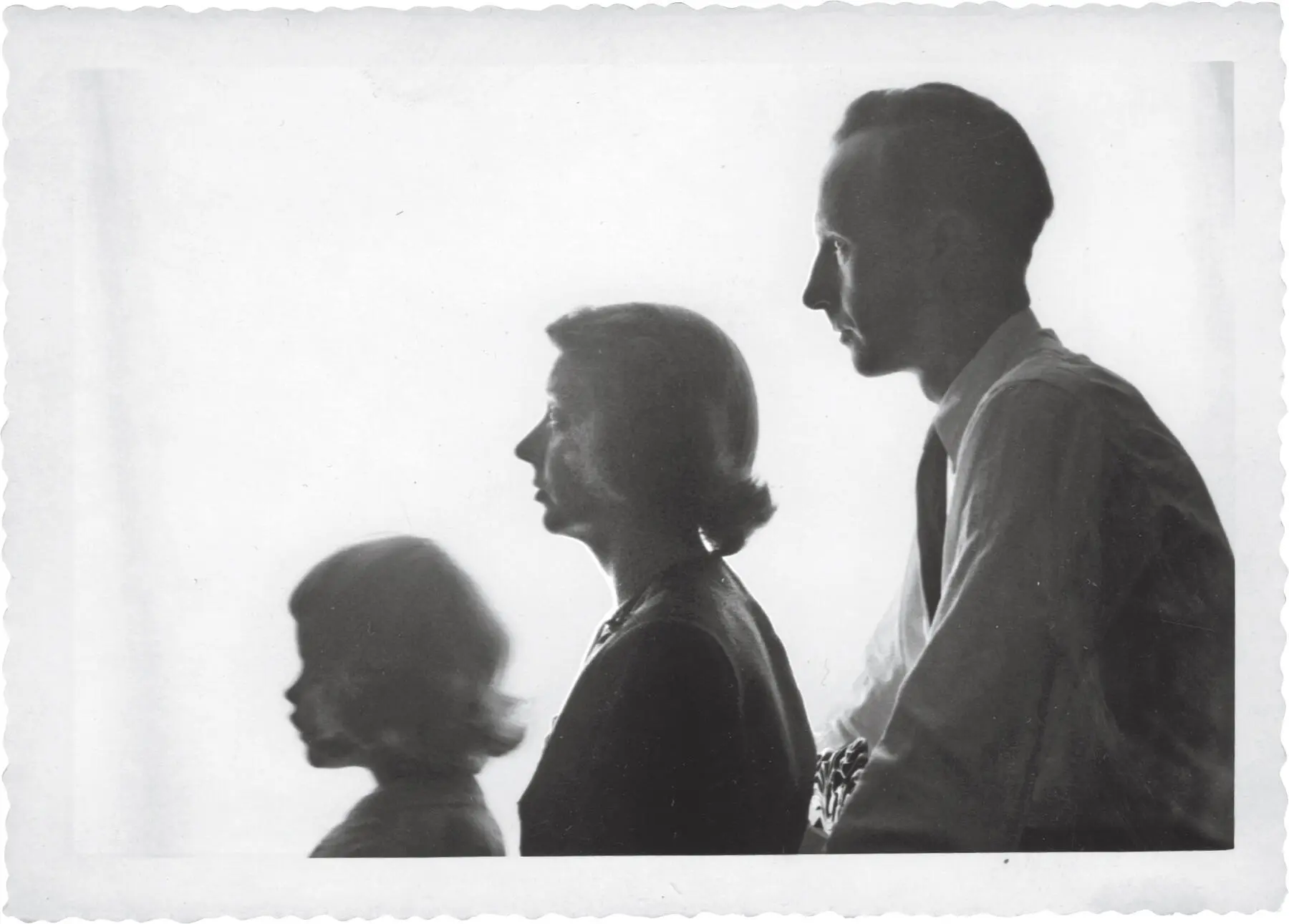

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

Coincidence . . . Coincidence came calling for me big-time in the early seventies. Coincidence: it’s supposed to mean just these random, disconnected events that concur or collide. But coincidence is not that at all. It’s the stuff that’s meant to be. Things that are supposed to be drawn together, as if by some extra-earthly magnetic force. Things that connect and become woven and then shoot off to form previously unimagined combinations. Small changes that tumble into a fresh dynamic—as coincidence and chaos give birth to a new creation. Coincidence: the “divine intervener” that pushes us to make happen what was always supposed to happen . . .

Nineteen seventy-two. Well, I was still in New Jersey and living with house painter Mr. C, but I’d drive into the city for my social life. I missed the downtown scene that I had dropped out of for a while. Seeing bands was a good way to meet people and make connections. One of my favorite things was to go see the New York Dolls. They were so exciting to watch. They were a real rock band. Their influences were Marc Bolan, Eddie Cochran, and many others, but they were so New York. They were straight but they dressed in drag, at a time when the cops were still raiding gay bars. They were ragged and raunchy and uninhibited, strutting, swaggering about in their tutus, leatherette, lipstick, and high heels.

The first time I saw them was at the Mercer Arts Center. A labyrinthine place with lots of different rooms, it was built as an annex to the much-neglected, ancient, and very run-down Broadway Central Hotel. It opened near the end of 1971 and closed less than two years later when the hotel actually collapsed, taking the arts center with it. But for that short time, it had its own scene that was fun, cool, and influential. Eric Emerson used to play there with his band the Magic Tramps. They were the first real glitter band in New York, very visually exciting. Their roadie and occasional bass player, who was Eric’s roommate for a time, was a young guy from Brooklyn named Chris Stein. But we hadn’t met each other yet.

I had a big crush on David Johansen, who I thought was just fantastic. I made it with him once. He shared an apartment with Diane Podlewski, who always came into Max’s after midnight. They were the most interesting-looking people and just stood out; they were stunning. These were the night creatures and they fascinated me.

I can’t remember how, but I became friends with the Dolls. Since almost nobody in downtown New York had a car, I would sometimes drive them around. I remember one time that the Dolls wanted to meet with Paramount’s head of A & R, Marty Thau, who lived upstate, but they said they had no way to get there. My father had a huge turquoise Buick Century, so I borrowed it—this boat on wheels . . . I had the entire band and some of their girlfriends in the car—all so skinny, they were able to squeeze six across the backseat and four across the front.

Bobby Grossman

Well, the car broke down. My father had warned me not to use the AC, because the alternator regulator wasn’t working. But it was a blazing-hot day. So I used the AC and the car went dead. So there we were, plomped at the side of the road—we didn’t have cell phones in those days—when the police pulled up. When they saw all of us with the hair and the clothes and the makeup they didn’t say a word. The car had to be towed and repaired. I don’t know how I paid for it because I didn’t have any money or a credit card. But somehow we got the car going again and I managed to get them to their meeting with Marty.

Turns out that trip was worth all the hassle. Shortly thereafter, Marty quit Paramount to become the Dolls’ manager.

Mr. C did not like my disappearing to New York at all. He was one of the many people at that time who were afraid to go to New York City. Their idea of New York was that it was filthy and dangerous, full of no-go areas and rampant crime. There had been a massive white flight to the suburbs. Times Square belonged to the dealers and hookers; a trash-strewn Central Park was plagued by muggers and rats. The city couldn’t pay its workers. No one with money would venture below Fourteenth Street. However the upside was all these abandoned buildings, which were a magnet for artists, musicians, and freaks. But I think what really pissed Mr. C off most about my going to the city was that I wasn’t under his control.

Читать дальше