Morris offered a way to get beyond the deference to Latin and Greek that he believed had made earlier grammarians so error-prone: he advocated observing English carefully, and then making rules based on those observations, rather than trying to squeeze English grammar into frameworks designed for dead languages.‡‡ Grammar rules would then arise directly from scrutinising English in action – and conveniently enough, the study of grammar would thus acquire for itself some of the virtues of the natural sciences that were being championed in the press, where commentators regularly argued that students were inherently inclined towards the observation and study of natural phenomena.

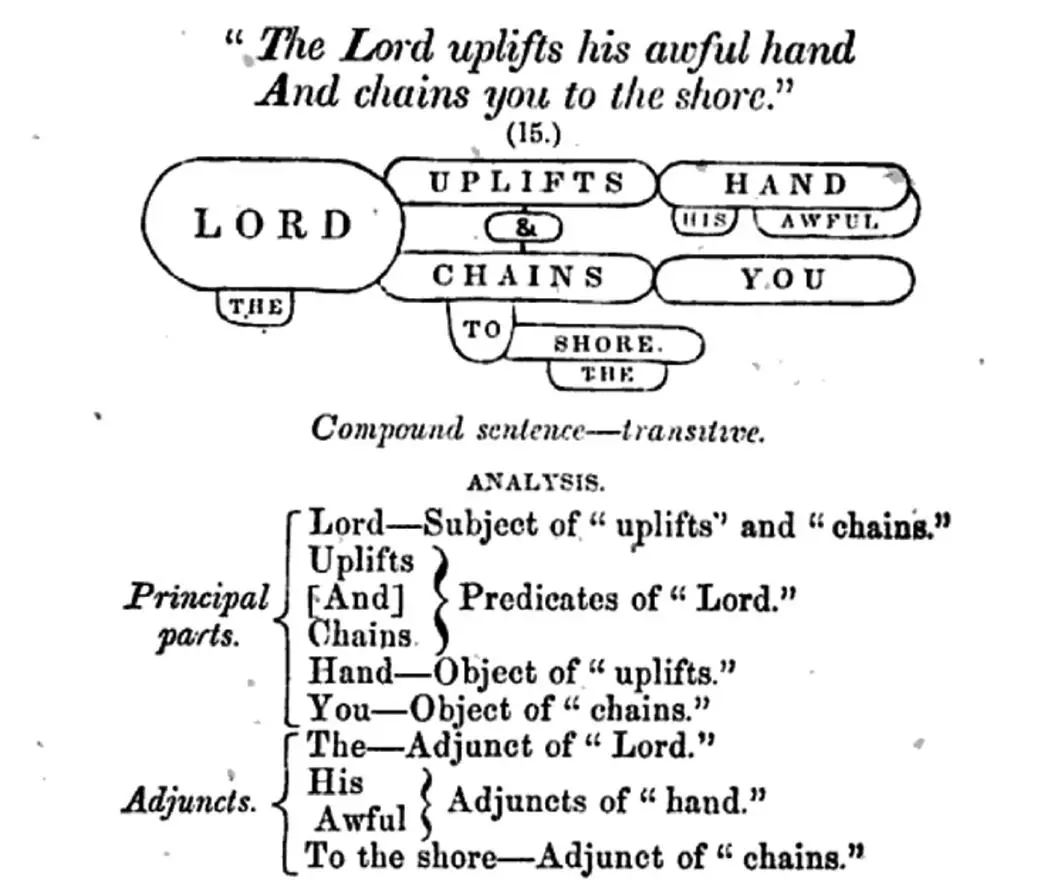

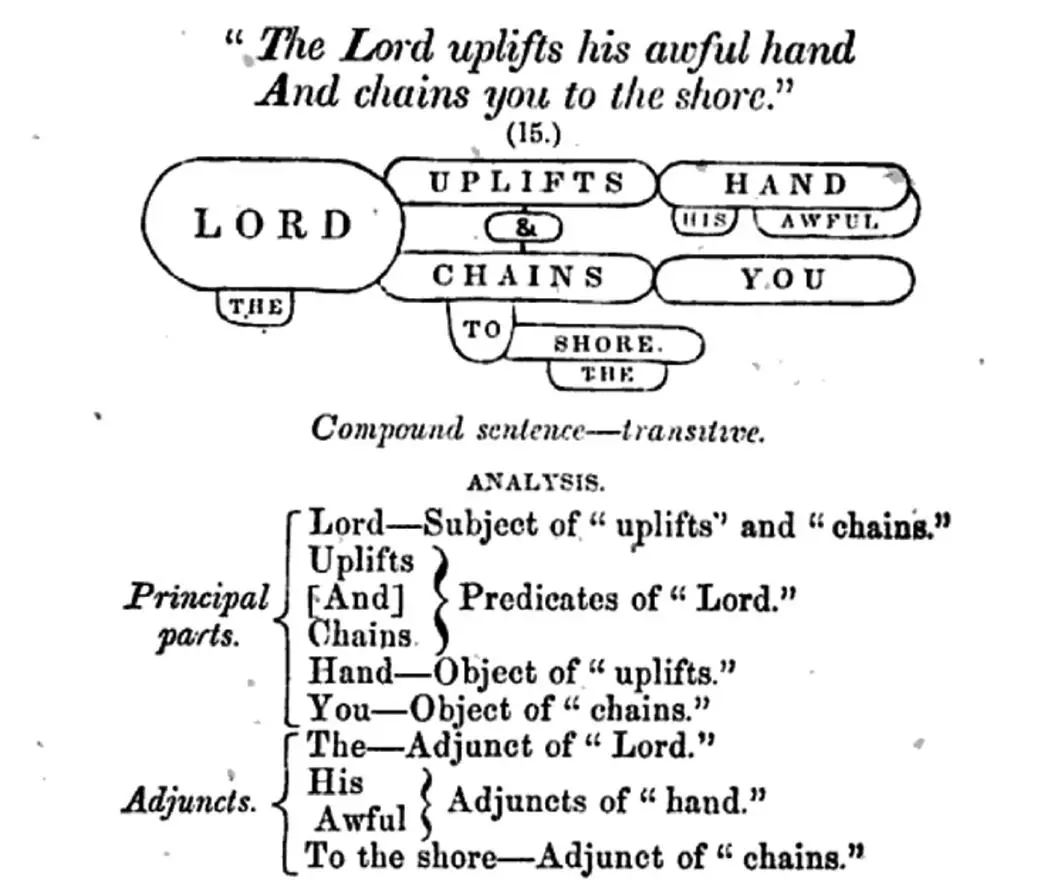

Grammarians had a second strategy to advance against critics who complained about the inferiority of grammar when compared to the natural sciences: the sentence diagram. Any good science textbook had diagrams, and if grammar was to be a science, it surely needed a system of schematic illustrations as well. And so in 1847, a grammarian named Stephen Clark introduced a system of diagrams designed to relate to the ‘Science of Language’ as maps did to geography, and figures to geometry and arithmetic. (It might sound odd to the modern reader to think of geography and geometry as natural sciences like physics and chemistry, but plenty of people back in Clark’s days thought of them that way, and even people who didn’t categorise those areas of study as ‘sciences’ believed the two disciplines were essential for the study of both the natural sciences and other respected fields like philosophy. And, unlike grammar, the mathematical sciences were considered ‘perfect’ and ‘useful’.)

Clark’s diagrams often made use of Bible verses: might as well pack in a few fearsome reminders about the powers of the Almighty for those schoolchildren misbehaving in the back of the class, after all.

The diagrams were a popular addition to grammar books, and held on for a long time. Although they’ve fallen out of pedagogical fashion these days, some readers may remember grammar classes from their childhoods that relied heavily on diagramming sentences on the blackboard. I certainly do, although I don’t recall ever having to produce anything quite so comically elaborate as this humdinger.

Clark, who invented the sentence-diagramming technique to visualise language, did his best to make the rest of his grammar follow the definitive-sounding, principle- and fact-heavy aesthetic of the natural sciences in other ways, too. Clark’s rules were set up in an outline form, which Clark borrowed from his contemporary Peter Bullions. Bullions had used outlines to show his readers ‘leading principles, definitions, and rules’. Those rules were to be displayed ‘in larger type’ to emphasise their importance; and exceptions to the rules were printed in type that got smaller and smaller the further away from an ironclad principle they crept.

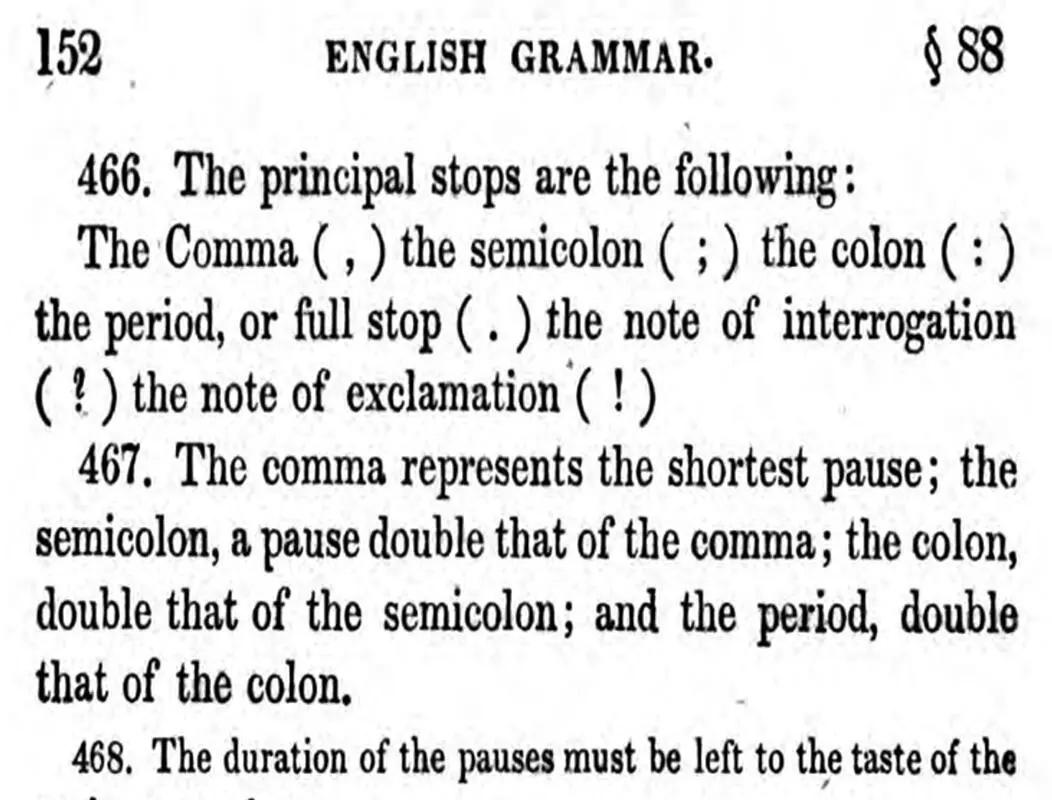

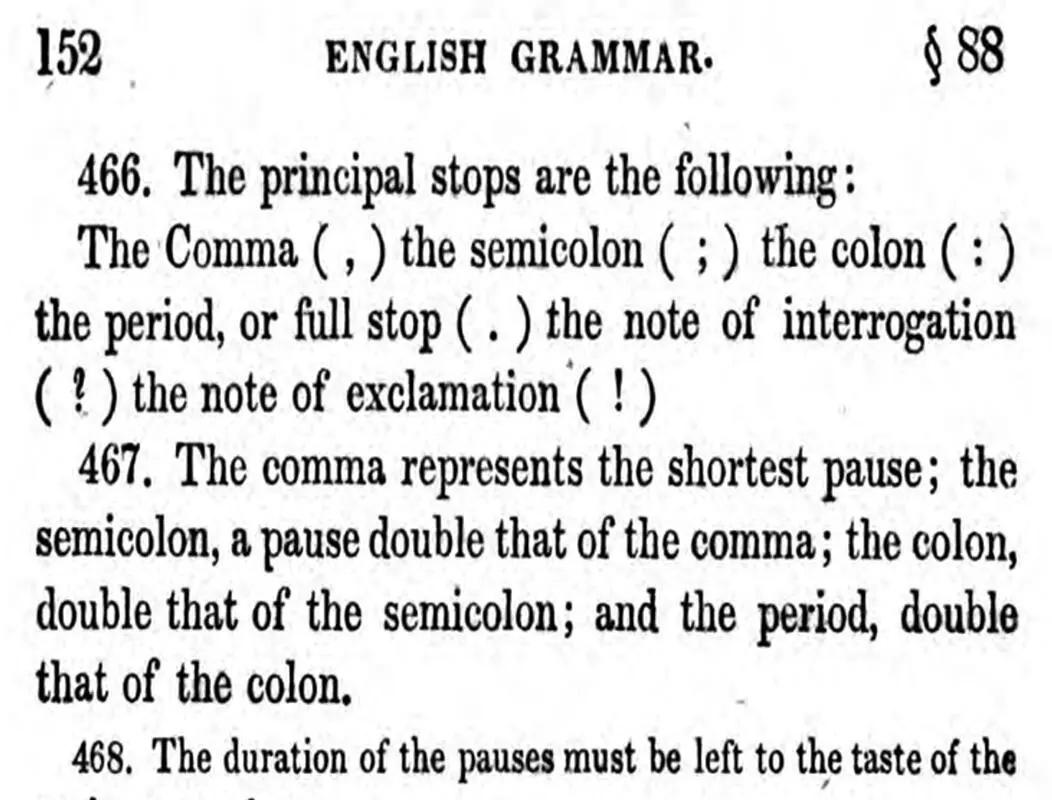

In Bullions’s nesting-doll fonts a fundamental tension is writ large: the conflicting demands of rules and taste . Bullions wrote that the purpose of punctuation was ‘to convey to the reader an exact sense, and assist him in the proper delivery’. He warned, however, in a font two points smaller, that ‘the duration of the pauses must be left to the taste of the reader or speaker’. Nevertheless, he then provided twenty-five rules and exceptions for the comma alone. These rules were then followed by yet another disclaimer in even tinier font than the first: ‘The foregoing rules will, it is hoped, be found comprehensive; yet there may be some cases in which the student must rely on his own judgment.’ Bullions seems to be equivocating, vacillating between committing to rules on the one hand, and capitulating to taste on the other.

Bullions and the tension between rules and taste.

Bullions’s dilemma was every nineteenth-century grammarian’s nightmare: how could it be possible to give useful rules for punctuation, while at the same time acknowledging that those rules couldn’t describe every valid approach to punctuating a text? Whether a grammarian tried to police English with the laws of ancient Latin and Greek, or instead to derive his principles from examination of contemporary English in action, he could not escape the tension between the rigidity of rules and the flexibility of usage. Even if English writers’ actual practices were taken into account and described in the rules, once laid down, the rules couldn’t shift, while usage inevitably did. The grammarian was necessarily torn between trying (and inevitably failing) to anticipate every kind of usage, as Peter Bullions did with his twenty-five comma rules; or giving rules so general they were scarcely rules at all, the strategy Robert Lowth opted for with his specification that punctuation marks were successively longer pauses.§§ Mega-meta-grammarian Goold Brown, in >his exhaustive Grammar of English Grammars , attempted to honey this problem with a bit of aspirational rhetoric:

Some may begin to think that in treating of grammar we are dealing with something too various and changeable for the understanding to grasp; a dodging Proteus of the imagination, who is ever ready to assume some new shape, and elude the vigilance of the inquirer. But let the reader or student do his part; and, if he please, follow us with attention. We will endeavor, with welded links, to bind this Proteus, in such a manner that he shall neither escape from our hold, nor fail to give to the consulter an intelligible and satisfactory response. Be not discouraged, generous youth.

Brown’s labours may have been Herculean in scope, but they were still insufficient to solidify the fluid laws of grammar. Whenever grammarians tried to pin down punctuation marks with rules, they inevitably slipped their restraints, no matter whether they were shackled with a few broad rules or a hundred narrow ones. This Proteus didn’t stop shifting shapes, it was just that now he had a heavy chain awkwardly dangling from his heels as he did so. The thorny relationship between rules and usage came to play a major role in the fate of our hero, the semicolon.

*I’m surprised he could bring himself to use a selection. Brown was a thorough guy, the type of person who dated his copy of Churchill’s English Grammar ‘AD 1824’, lest anyone mistakenly think he might have bought it in 1824 BC.

†My copy of Brown’s compendium is a menacing leather-bound brick measuring 9¾ inches by 6½ inches by 3 inches and tipping the scales at 4 pounds 15 ounces. It’s caused my checked baggage to violate airline weight allowances on three occasions.

‡Lowth, obviously, was English – unlike Brown, the American meta-grammarian who opened this chapter. I’ll bounce back and forth across the Atlantic throughout this chapter, but not without reason. In the nineteenth century, the most influential grammar books enjoyed the same freedom to be bought, taught, and sold on both sides of the pond. This makes a good deal of sense when you think about it: in matters of grammar, differences between British and American English are far slighter than in matters of vocabulary and idiom. In this respect, the distinction between American and British English is analogous to distinctions you’ll have encountered within Britain itself: whether you put your bacon on a cob, bap, barm, bun, or roll, you were taught the same grammar rules in primary school as anyone you meet from another region. And that’s not the only reason nineteenth-century grammar books were able to slip across borders so easily; frequently the matters on which American and British punctuation have come to differ weren’t even mentioned in the books. Peter Bullions, for instance, a New Yorker whose grammar had one of the longer sections on punctuation available at the time, doesn’t say a word about where punctuation should fall relative to quotation marks. Whether you want your full stops and commas included in (American style) or excluded from (British style) the quotation mark’s embrace, you’d find nothing in many of the original grammar rule books to help or hinder you. Even Noah Webster, who advocated fiercely for a uniquely American language befitting a unique new government, didn’t distinguish between American and British punctuation styles in his 1822 grammar book. And Robert Lowth, the Englishman we’re now discussing, used full stops after abbreviations like ‘Mr.’, which we now think of as American-style punctuation.

Читать дальше