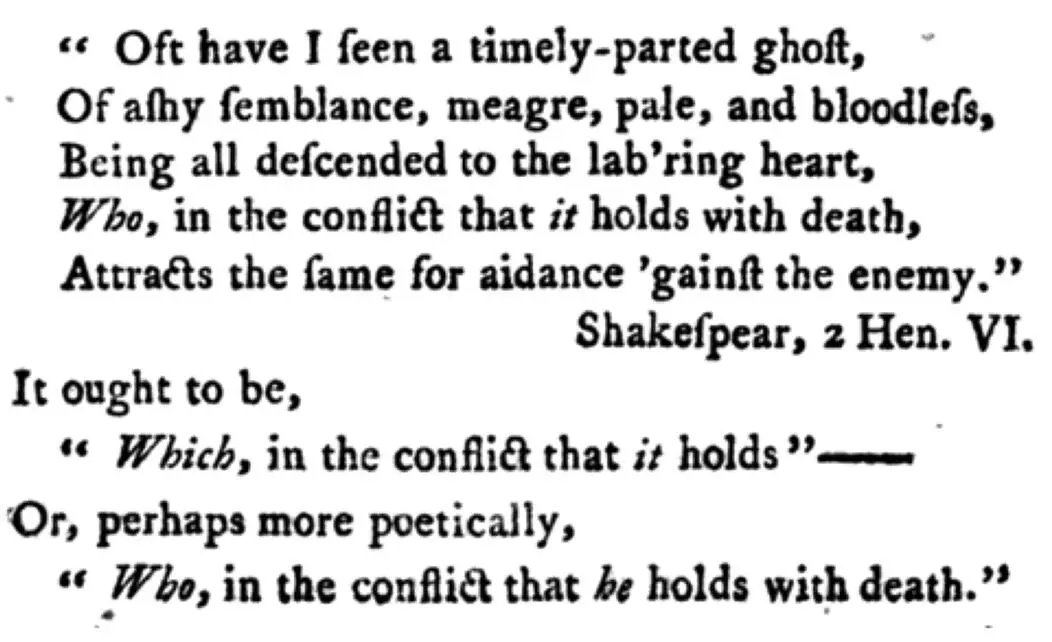

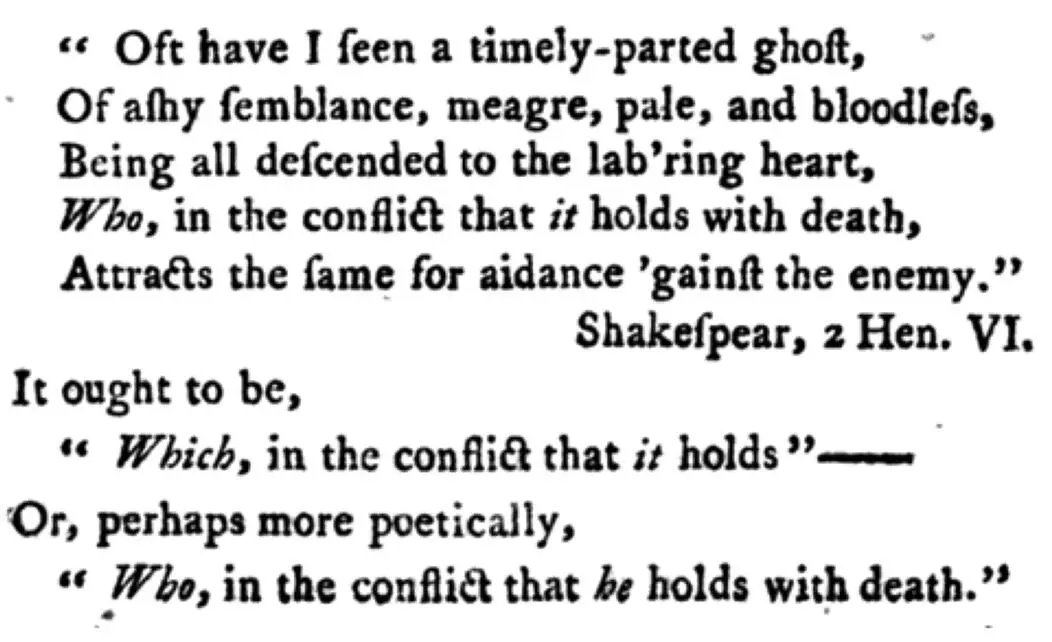

Lowth giving Shakespeare a little lesson in grammar and poetry writing.*

*You will notice an odd typographical quirk in Lowth’s text: the ‘Medial S’, which looks to the modern eye like an f but is to be read as an s . The Medial S can lead to some unintentionally seedy reading in books that are reprinted in facsimile edition, like Antoine Lavoisier’s Elements of Chemistry , which contains a long section in which the author describes sucking air through a tube for an experiment.

Just as Murray found success renovating Lowth’s foundations, so Murray’s grammar had some additions nailed on by another upstart grammarian, Samuel Kirkham. Kirkham’s 1823 grammar gradually displaced its archetype. Where Murray’s grammar had gone into a dizzying twenty-four editions, Kirkham’s went into at least one hundred and ten . Kirkham won over readers by presenting a new system of parsing verbs, and by extending his predecessors’ criticisms of ‘false syntax’ in historical English. Even as Kirkham’s book represented a further step towards more rules and more systematisation, the very first edition of his grammar omitted punctuation entirely, on the grounds that it was part of prosody rather than grammar: in other words, punctuation was all about establishing rhythm, intonation, and stresses. This stance got Kirkham some critical reviews, however; as a consequence, subsequent editions covered punctuation – but only briefly, and only by nebulously describing punctuation marks as pauses of varying lengths. Thus, for the king of nineteenth-century grammar-book sales, punctuation remained a tool that writers could wield with a good bit of flexibility and discretion.

With sales of his book so high, Kirkham was in the spotlight. Not only did that open him up to attack, but it even allowed him to cultivate a proper nemesis . That nemesis was Goold Brown, the grammar surveyor in whose gargantuan book Kirkham was but one of hundreds of other people plying the same trade. But out of all those grammarians, Kirkham was the one who most got under Brown’s skin. As Brown saw it, Kirkham had played fast and loose with grammar, and cared more about his bottom line than about scientific scruples: he wanted to ‘veer his course according to the trade-wind’ , Brown sniped. In Brown’s eyes, when Kirkham revised his grammar book to include punctuation, the additions represented not honest scholarly progression but mercenary modifications: ‘his whole design’ was a ‘paltry scheme of present income’. And – Brown added – Kirkham’s character was such that he was ‘filled with glad wonder at his own popularity’. Labelling Kirkham a quack and a plagiarist, Brown tore into his grammar book on page after page, pointing out its logical contradictions and omissions. Interspersed with these ad librum jabs are some choice ad hominem sucker punches. In one particularly efficient passage, Brown calls out Kirkham’s reasoning while also claiming that he didn’t write his own book and insinuating that he was too cheap to pay his ghostwriter adequately:

As a grammarian, Kirkham claims to be second only to Lindley Murray; and says, ‘Since the days of Lowth, no other work on grammar, Murray’s only excepted, has been so favorably received by the publick as his own. As a proof of this, he would mention, that within the last six years it has passed through fifty editions.’ – Preface to Elocution , p. 12. And, at the same time, and in the same preface, he complains, that, ‘Of all the labors done under the sun, the labors of the pen meet with the poorest reward.’ – Ibid. , p. 5. This too clearly favours the report, that his books were not written by himself, but by others whom he hired. Possibly, the anonymous helper may here have penned, not his employer’s feeling, but a line of his own experience. But I choose to ascribe the passage to the professed author, and to hold him answerable for the inconsistency.

Kirkham answered Brown’s complaints about his boasting with … more boasting, this time underlined with populist rhetoric aimed at his American readers:

What! A book have no merit, and yet be called for at the rate of sixty thousand copies a year ! What a slander is this upon the public taste! What an insult to the understanding and discrimination of the good people of these United States! According to this reasoning, all the inhabitants of our land must be fools, except one man, and that man is GOOLD BROWN!

Brown bit back, pointing out that Lord Byron got paid a lot more for Childe Harold than Milton did for Paradise Lost ; but would anyone say Byron was the greater literary genius?

Brown and Kirkham may have pitted themselves against one another,§ but they (along with their contemporaries) agreed on one thing: grammar was to be viewed not as a mere matter of personal taste or style, but now as a coherent system of knowledge. Accordingly, they termed grammar a ‘science’. In the middle of the nineteenth century, however, a new wave of grammarians began to argue that grammar wasn’t just a science in this broad sense of schematic knowledge, but a science in the narrower sense in which we use the word nowadays. To these new grammarians, their field was analogous to the natural sciences.

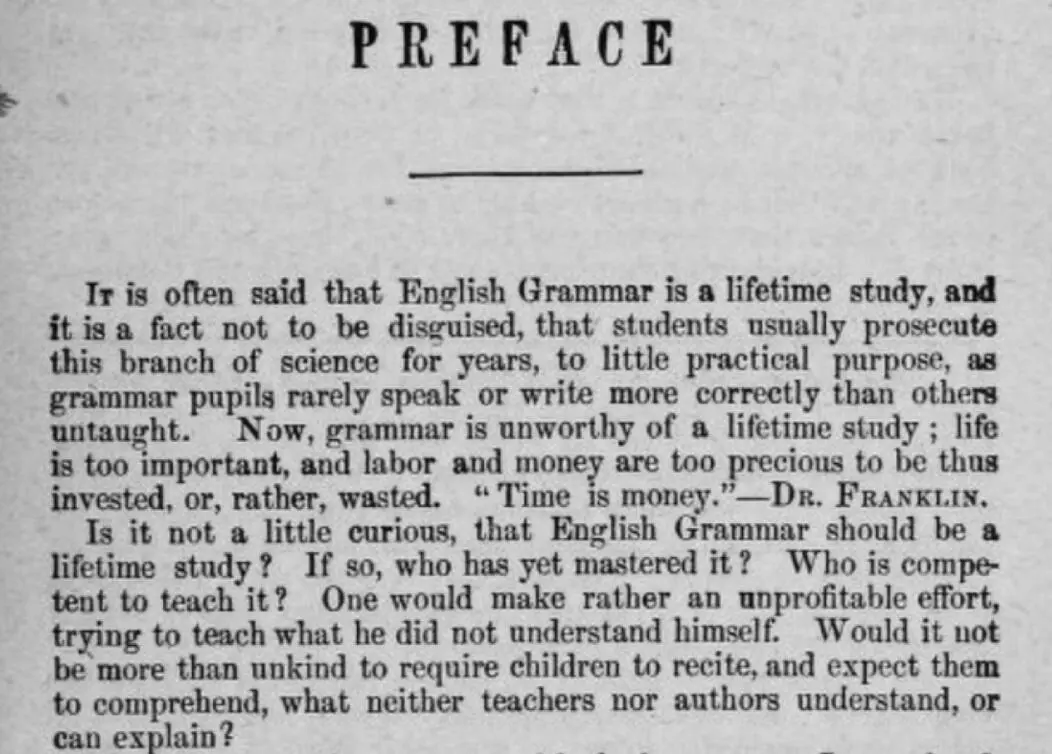

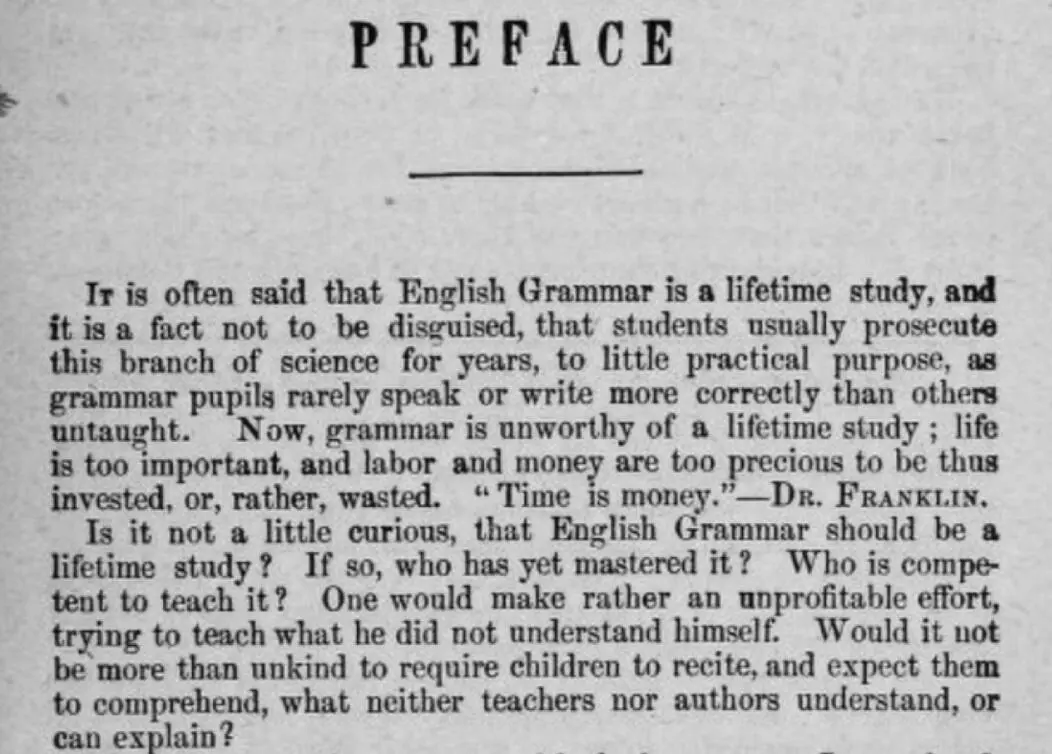

In staking this claim, the new grammarian-scientists were almost certainly reacting to protests from parents of schoolchildren and school officials, who claimed that the study of grammar was boring and ineffectual; pupils’ time was better spent studying the natural sciences, which were exciting and taught real skills. Complaints about the mind-numbing uselessness of grammar surfaced as early as 1827, came to a boil by 1850, and persisted through the rest of the nineteenth century. If grammarians wanted to stay relevant and sell those lucrative grammar books to schools and their pupils, they needed to answer to carping parents and officials. In a few cases, grammarians peddled their wares with novelty methods and titles that smacked of circus-barker enthusiasm: British grammarian George Mudie perhaps epitomised this trend with his 1841 book, The Grammar of the English Language truly made Easy by the Invention of Three Hundred Moveable Parts of Speech. Truly, what could be easier or more fun than 300 moveable parts of speech?¶

More often, however, grammarians answered to complaints about grammar’s relative dullness and uselessness with rather ingenious rhetoric: grammar, they proposed, was a method of teaching students the art of scientific observation without requiring expensive or complex scientific apparatus. In service of this goal of teaching scientific skills, grammarians resolved to employ careful observation of English, because this gave them a way to use the methods of science to refine grammar; and they imported into their grammars some of the conventions of science textbooks, such as diagrams.

Isaiah J. Morris, ‘offensive’ from the very first page.

Rebel American grammarian Isaiah J. Morris emphasised the first approach – careful observation of English – in his 1858 Morris’s grammar: A philosophical and practical grammar of the English language, dialogically and progressively arranged; in which every word is parsed according to its use. ** Morris came out swinging from the start, distancing himself from reigning champions of grammar like the bestselling Samuel Kirkham. Kirkham and his ilk had relied on Greek and Latin grammar to come up with rules for English, and as a result, Morris fumed, they had littered the true ‘laws of language’ with ‘errors’ and ‘absurdities’, which Morris was now left to ‘expose and explode’. Correcting these mistakes was a moral obligation: ‘Shall we roll sin under our tongues as a sweet morsel?’ Morris demanded. ‘It must be sin to teach what we know to be error.’ In order to cleanse English grammars of these corruptions, Morris devoted the preface of his grammar to eviscerating the stale precepts of his predecessors. He knew that shredding such venerable grammarians would shock his readers: ‘If the truth be disagreeable,’ he shrugged, ‘I choose to be offensive.’††

Читать дальше