I wouldn’t deny that there’s joy in knowing a set of grammar rules; there is always joy in mastery of some branch of knowledge. But there is much more joy in becoming a reader who can understand and explain how it is that a punctuation mark can create meaning in language that goes beyond just delineating the logical structure of a sentence. Great punctuation can create music, paint a picture, or conjure emotions. This book will show you how the semicolon is essential to the effectiveness and aesthetic appeal of passages from Herman Melville, Raymond Chandler, Henry James, Irvine Welsh, Rebecca Solnit, and other masters of English fiction and non-fiction. Looking at these authors, we will see beautiful uses of the semicolon that cannot be adequately encapsulated in grammarians’ rules, nor explained simply as a ‘breaking’ of those rules.

Still, inadequate and artificial as grammar rules are, I understand what it’s like to love them. In fact, I’m a reformed grammar fetishist myself, the sort of person who used to feel that her love for English was best expressed by means of irritation at the sight of a misplaced apostrophe, or outright heart palpitations over a comma splice. My own dive into the history of the semicolon was precipitated by a fight over one that my PhD adviser, Bob,* had circled in one of my papers, alleging that it violated the precepts of The Chicago Manual of Style (at the time, Bob was chair of the board of the press that publishes the Manual ). I insisted that the semicolon in question was a perfectly legitimate interpretation of one of the umpteen semicolon rules the Manual laid out, and round and round Bob and I went for weeks, grandstanding about the meaning of the Manual ’s rules. Finally, during one of these heated debates, it occurred to me to wonder: Where do they come from, these rules I cherish so much, and believe I know so well?

Answering that question took me on a ten-year journey through piles of dusty grammar books that had lain untouched on library shelves for decades, and more often centuries. Some, having been forgotten for so long, collapsed in my hands; others left my palms tinted a guilty red with rot from their decaying leather bindings. But the words inside those old grammar books had lost none of their liveliness and passion, and I soon became absorbed in the drama of grammarians’ attempts to create a market for their rules in the face of an initially sceptical public. The story that I began to piece together from their pages called on all my skills as an academic. It demanded my expertise in the history of science: grammar rules, it turns out, began as an attempt to ‘scientise’ language, because science was what parents wanted their children to be taught in public [state] schools. Equally, the story of the semicolon called on my training in philosophy, as I began to wonder what ethical imperatives knowing the true history of grammar rules might impose. And finally, crucial to making sense of the story of the semicolon were my years of experience teaching writing at institutions like Yale, the University of Chicago, and Bard College.

By the time I had finished writing the story contained in these pages, I had changed everything about how I looked at grammar. I still love language, but I love it in a richer way. Not only did I become a better and more sensitive reader and a more capable teacher, I also became a better person. Perhaps that sounds like a fancifully hyperbolic claim – can changing our relationship with grammar really make us better human beings? By the end of this book, I hope to persuade you that reconsidering grammar rules will do exactly that, by refocusing us on the deepest, most primary value and purpose of language: true communication and openness to others.

But before I can try to persuade you of this, we have to look the past square in the face. Ever since grammar rules were invented, they have caused at least as much confusion and distress as they have ameliorated; and people living one hundred years ago had passions about semicolons that varied from decade to decade and person to person. In this regard, they aren’t so different from us after all: when you looked at the semicolons on the front of this book, you probably felt something. Was it hate, like Paul Robinson? Anger? Love? Curiosity? Confusion? The diminutive semicolon can inspire great passion. As you’ll see in the chapters that follow, it always has.

*Robert J. Richards at the University of Chicago. As of 28 March 2018, Bob’s entry on Wikipedia contains semicolon usage that I’m quite certain would rankle him: ‘Richards earned two PhDs; one in the History of Science from the University of Chicago and another in Philosophy from St Louis University.’ Bob, I swear it wasn’t me!

I

Deep History

The Birth of the Semicolon

The semicolon was born in Venice in 1494. It was meant to signify a pause of a length somewhere between that of the comma and that of the colon, and this heritage was reflected in its form, which combines both of those marks. It was born into a time period of writerly experimentation and invention, a time when there were no punctuation rules, and readers created and discarded novel punctuation marks regularly. Texts (both handwritten and printed) record punctuation testing and tinkering by fifteenth-century literati known as the Italian humanists. The humanists put a premium on eloquence and excellence in writing, and they called for the study and retranscription of Greek and Roman classical texts as a way to effect a ‘cultural rebirth’ after the gloomy Middle Ages. In the service of these two goals, humanists published new writing and revised, repunctuated, and reprinted classical texts.

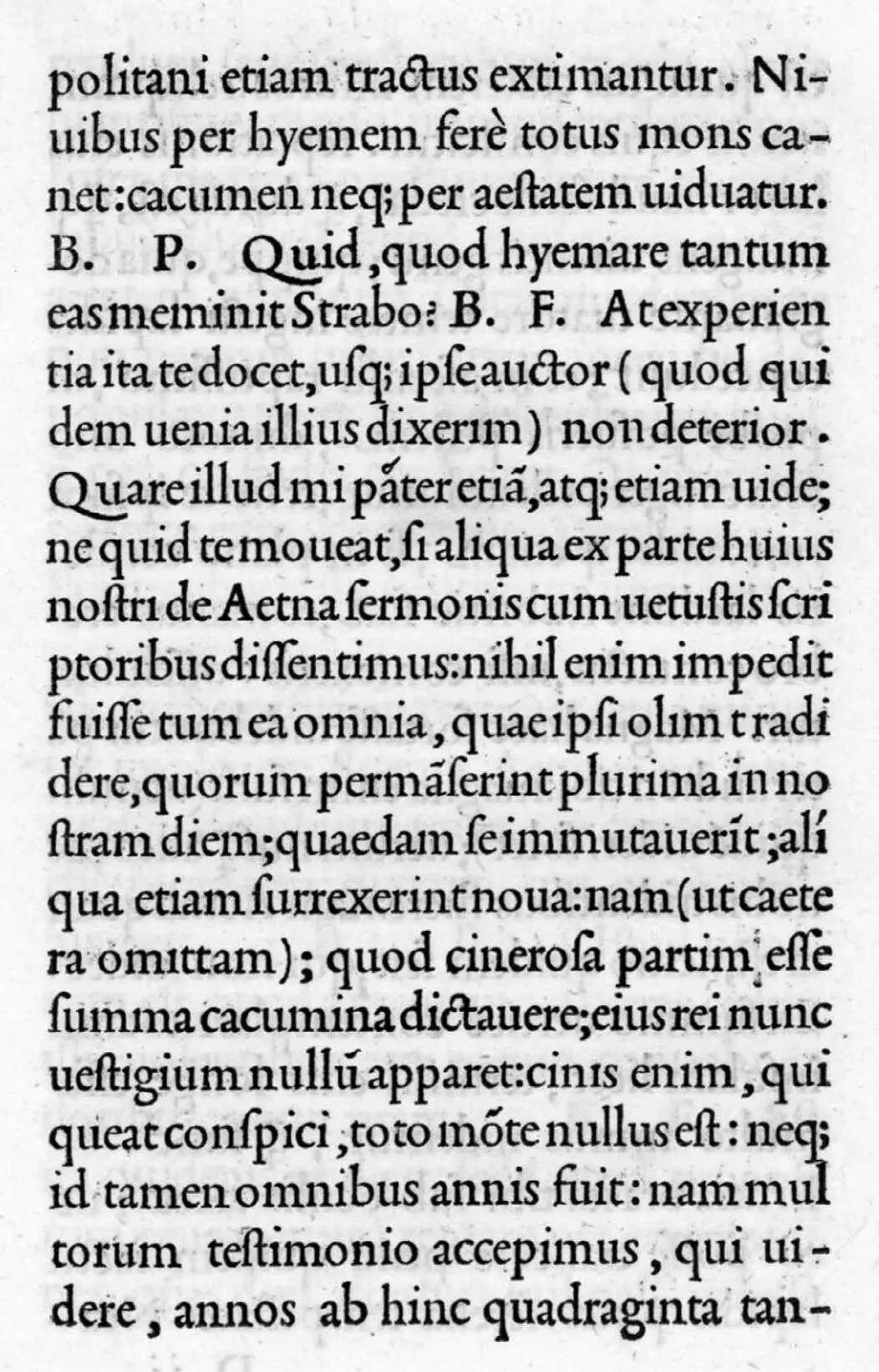

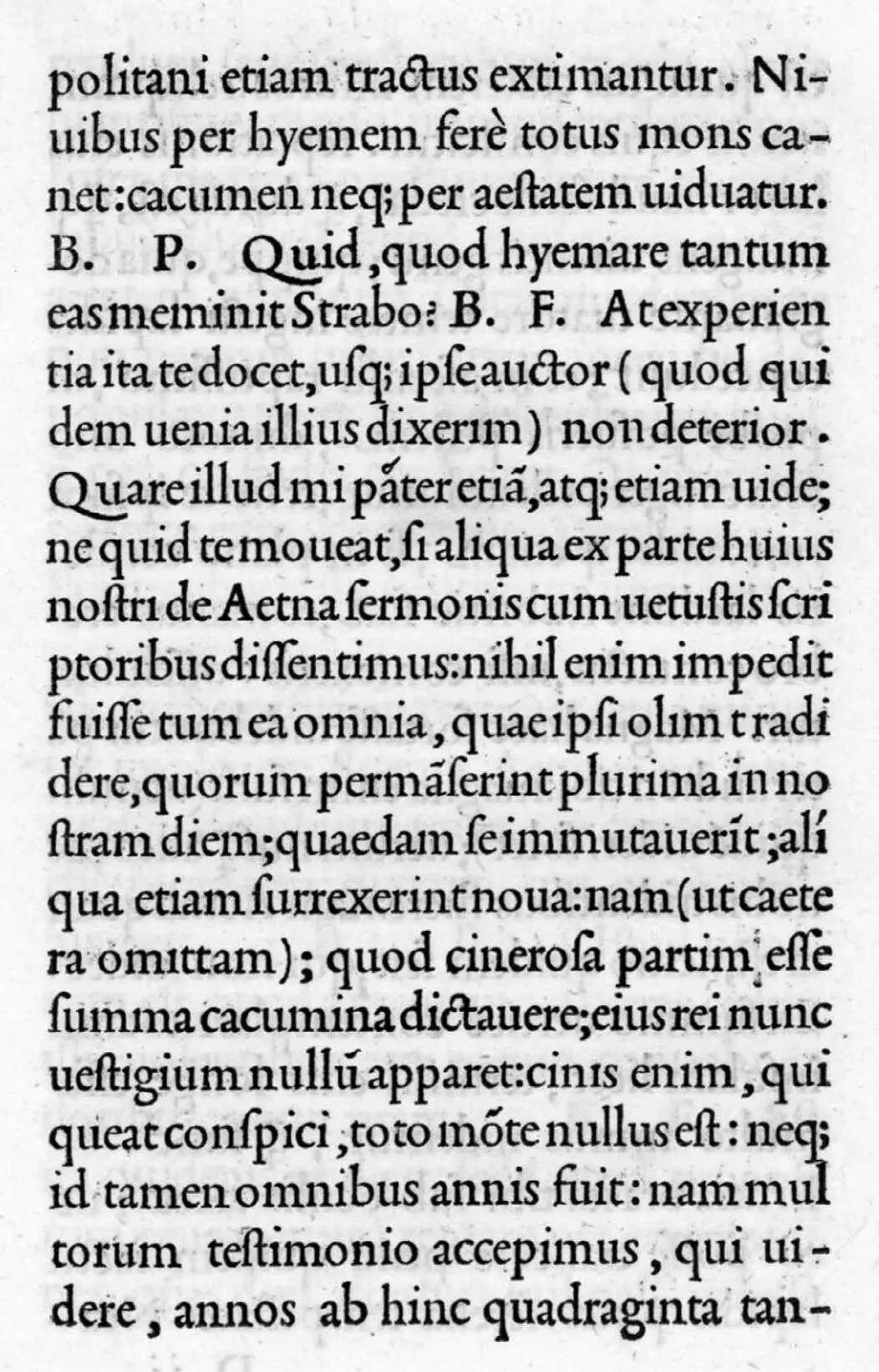

One of these humanists, Aldus Manutius, was the matchmaker who paired up comma and colon to create the semicolon. Manutius was a printer and publisher, and the first literary Latin text he issued was De Aetna , by his contemporary Pietro Bembo. De Aetna was an essay, written in dialogue form, about climbing volcanic Mount Etna in Italy. On its pages lay a new hybrid mark, specially cut for this text by Bolognese type designer Francesco Griffo: the semicolon (and Griffo dreamed up a nice plump version) is sprinkled here and there throughout the text, conspiring with colons, commas, and parentheses to aid readers.

In this snippet, you can see four of these brand-new semicolons. You might think you see eight, but beware! That semicolonish mark at the end of the fourth line from the bottom isn’t a semicolon, it’s an abbreviation for que , Latin for ‘and’. In this case, it’s helping to shorten neque , or ‘also not’. It appears elsewhere in the excerpt, always filling in the –ue part of a que . If you look closely, you’ll see that the dot-and-curve combination is raised higher up than a semicolon; it’s positioned on the same level as the words in the text because it’s shorthand for a word instead of a signal to pause.

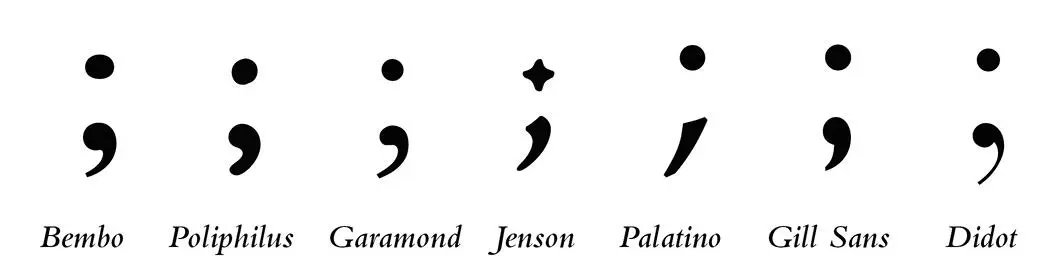

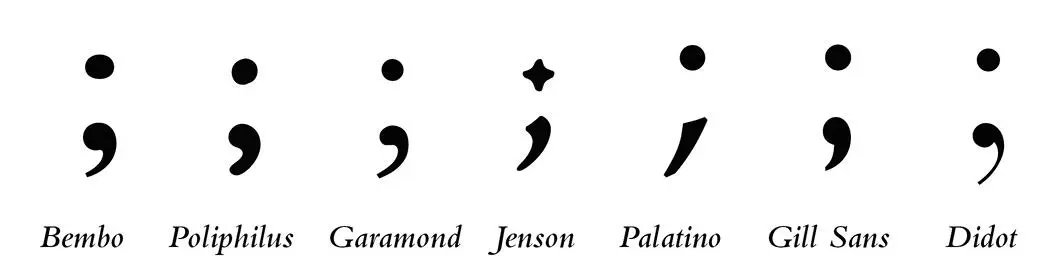

Nearly as soon as the ink was dry on those first semicolons, they began to proliferate, and newly cut font families began to include them as a matter of course. The Bembo typeface’s tall semicolon was the original that appeared in De Aetna , with its comma-half tensely coiled, tail thorn-sharp beneath the perfect orb thrown high above it. The semicolon in Poliphilus, relaxed and fuzzy, looks casual in comparison, like a Keith Haring character taking a break from buzzing. Garamond’s semicolon is watchful, aggressive, and elegant, its lower half a cobra’s head arced back to strike. Jenson’s is a simple shooting star. We moderns have accumulated a host of characterful semicolons to choose from: Palatino’s is a thin flapper in a big hat, slouched against the wall at a party. Gill Sans MT’s semicolon has perfect posture, while Didot’s puffs its chest out pridefully. (For the postmodernist writer Donald Barthelme, none of these punch-cut* disguises could ever conceal the semicolon’s innate hideousness: to him it was ‘ugly, ugly as a tick on a dog’s belly’.)

Читать дальше