The semicolon had successfully colonised the letter cases of the best presses in Europe, but other newborn punctuation marks were not so lucky. The humanists tried out a lot of new punctuation ideas, but most of those marks had short lifespans. Some of the printed texts that appeared in the centuries surrounding the semicolon’s birth look as though they are written partially in secret code: they are filled with mysterious dots, dashes, swoops, and curlicues. There were marks for the minutest distinctions and the most specific occasions. For instance, there was once a punctus percontativus , or rhetorical question mark, which was a mirror-image version of the question mark. Why did the semicolon survive and thrive when other marks did not? Probably because it was useful . Readers, writers, and printers found that the semicolon was worth the trouble to insert. The rhetorical question mark, on the other hand, faltered and then fizzled out completely. This isn’t too surprising: does anyone really need a special punctuation mark to know when a question is rhetorical?

In humanist times, just as in our own, hand-wringing sages forecast a literary apocalypse precipitated by too-casual attitudes to punctuation. ‘It is not concealed from you how great a shortage there is of intelligent scribes in these times,’ wrote one French humanist to another,

and above all in transcribing those things which observe style to any degree; in which unless points and marks of distinctions , by which the style flows through the cola , commata , and periodi , are separated with more attentive diligence, that which is written is confused and barbarous … Which carelessness, in my opinion, has occurred chiefly since we have for a long time lacked eloquence, in which these things are necessary: the ancient manner of handwriting, therefore, in which the scribes of books ( antiquarii ) were gradually writing a perfect and correctly formed script with precise punctuation ( certa distinctione ) of clausulae and with notes of accentuation, has perished together with the art of expression ( dictatu ).

The entire art of expression – dead, because careless writers just couldn’t hack it when it came to punctuation. Well, I think we moderns might maintain that the art of expression gave us a few rather decent literary works even after the date of this fifteenth-century letter. But the lament of the French humanists is familiar, isn’t it? People can’t punctuate correctly, eloquence is slowly dying out. Plus ça change.

Still, a few bad-tempered complainants notwithstanding, most humanists believed that each writer should work out his punctuation for himself,† rather than employing a predetermined set of rules. A writer or an annotating reader was to exercise his own taste and judgment. This idea of punctuation as a matter of individual taste and style outlived the humanists: it stretched beyond the Latin texts that Manutius printed, crossing borders and oceans, and it survived as a way of thinking about the practice of punctuation well into the eighteenth century. When the topic of punctuation usage came up, a reader was likely to be advised that he should consider the punctuation marks analogous to rests in music, and deploy them according to the musical effect he wanted to achieve. How on earth did this idea of the writer as musician, which held on for hundreds of years, transform into our comparatively new expectation that writers must submit to rigid rules?

*Back in the humanists’ day, the letters for a font were carved into steel bars. These were called ‘punches’. The technique was punch-cutting, and its practitioner a punch-cutter.

†In those days, it was usually a ‘him’, although there were of course exceptions.

II

The Science of Semicolons

English Grammar Wars

Goold Brown, an American schoolteacher and grammar obsessive, had a lofty ambition: he wanted to produce ‘something like a complete grammar of the English language’. Twenty-seven years after first resolving to undertake this task, he finally published The Grammar of English Grammars , which contained 1,192 pages filled with tiny print surveying a selection* of 548 English grammar books that had been published in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, up until the 1851 printing of his own book.†

Where were all of these grammar books that Goold Brown surveyed coming from, and what had made them explode in number so suddenly, after several quiet centuries of minimal punctuation guidance for writers? A jaunt through some of the most popular grammar books of the nineteenth century will reveal that their authors were shrewd entrepreneurs taking advantage of a newly developed and highly lucrative market for education in English writing; in both America and Britain, access to public education expanded exponentially over the course of the nineteenth century, and with it, the opportunity to make a killing supplying schools with teaching materials. These early grammarians were also masters of the biting insult, as they jockeyed for position (and market share) with one another. And – perhaps most surprisingly – they were aspiring scientists . We have to understand the great shift these authors created in the way people thought about English grammar in order to understand the semicolon’s transformation: although these first professional grammarians sought clarity through rules, they ended up creating confusion, and the semicolon was collateral damage.

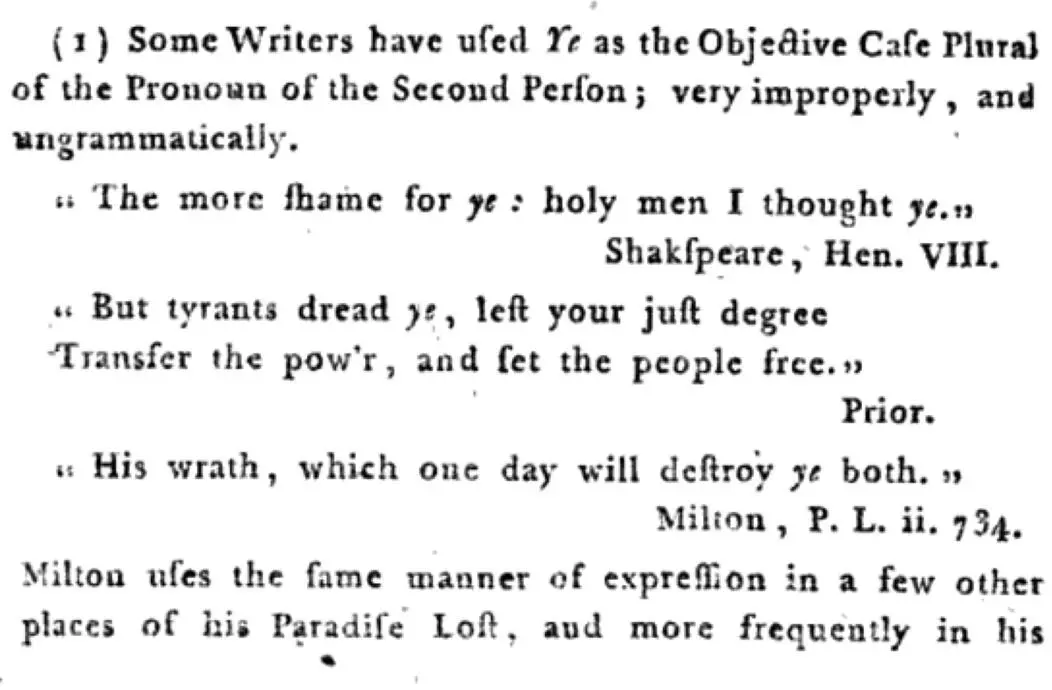

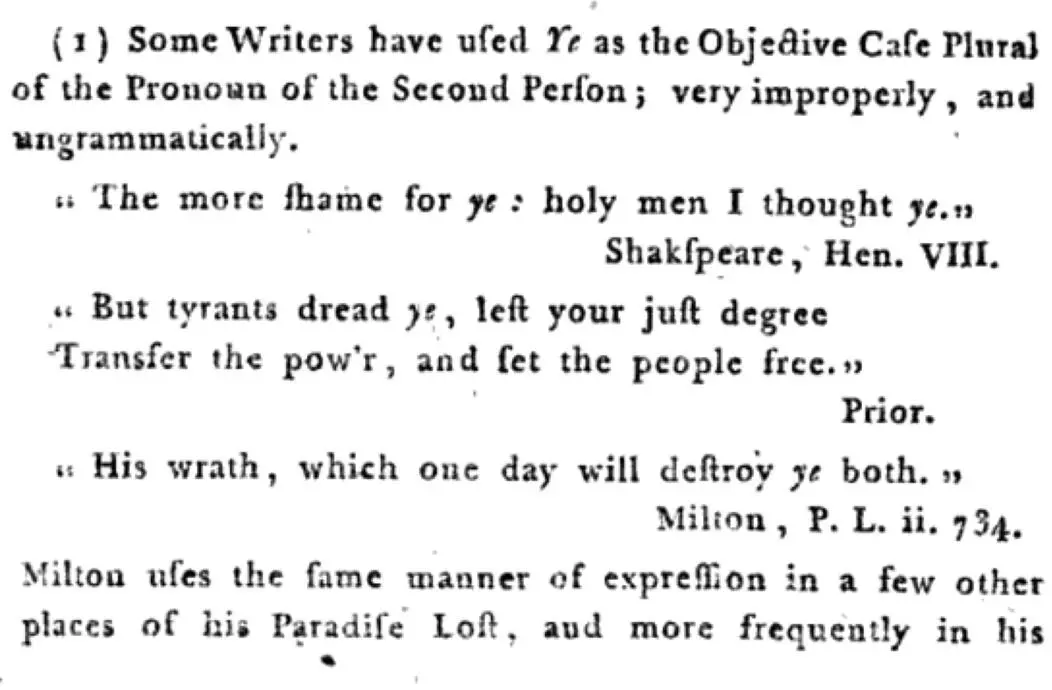

The first English grammar book to achieve lasting influence and popularity by creating laws for language was Robert Lowth’s 1758 A Short Introduction to English Grammar . Lowth, a bishop in the Church of England and a professor of poetry at Oxford,‡ used his platform to boldly announce that it was his aim to ‘lay down rules’ for grammar. These rules, he felt, were usually best presented by showing violations of them along with judicious corrections. Accordingly, he assembled examples from some of the very worst syntactical offenders available in English at the time – true grammatical failures including Shakespeare, Donne, Pope, Swift, and Milton.

Even though Lowth didn’t hesitate to perpetrate brow-raising ‘corrections’ on writers who seem, well, pretty competent, he did still carry with him the legacy of the previous centuries’ emphasis on personal taste and style, and he reserved a place for individual discretion, particularly when it came to punctuation. For punctuation, he acknowledged, ‘few precise rules can be given, which will hold without exception in all cases; but much must be left to the judgment and taste of the writer’. As we’ve seen before, the marks of punctuation were analogous to the rests in a piece of music, and were to be applied as individual circumstances and preferences dictated. The comma thus was a pause shorter than the semicolon, and the semicolon was a pause shorter than the colon.

Shakespeare and Milton, both very improper!

Lowth’s book reigned supreme in both the UK and the US for a couple of decades, until an American grammarian, Lindley Murray, came along and decided he could probably sell a few books himself if he tweaked Lowth’s work a bit by increasing its structural precision and its rigidity. In order to rebuild the book in this way, he divided it into sections and numbered its rules. Murray retitled this new version English Grammar . To say that English Grammar was a blockbuster success is an understatement. The book went into twenty-four editions, reprinted by sixteen different American publishers between 1797 and 1870, and it sold so many copies that Murray was ‘the best-selling producer of books in the world ’ between 1800 and 1840.

Читать дальше