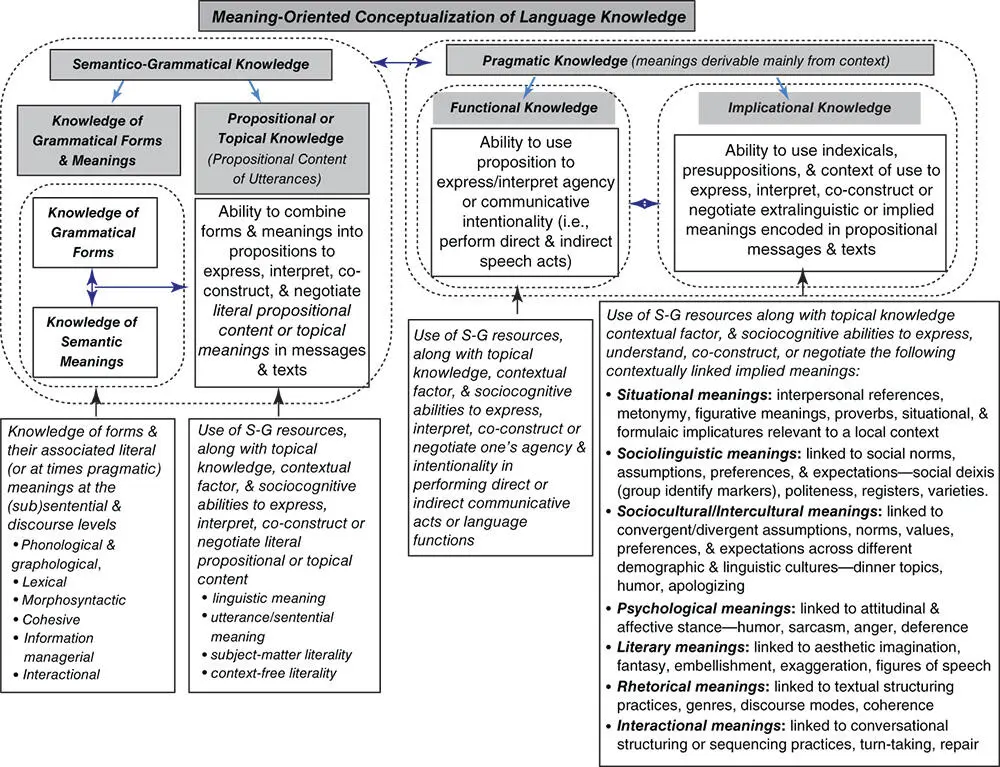

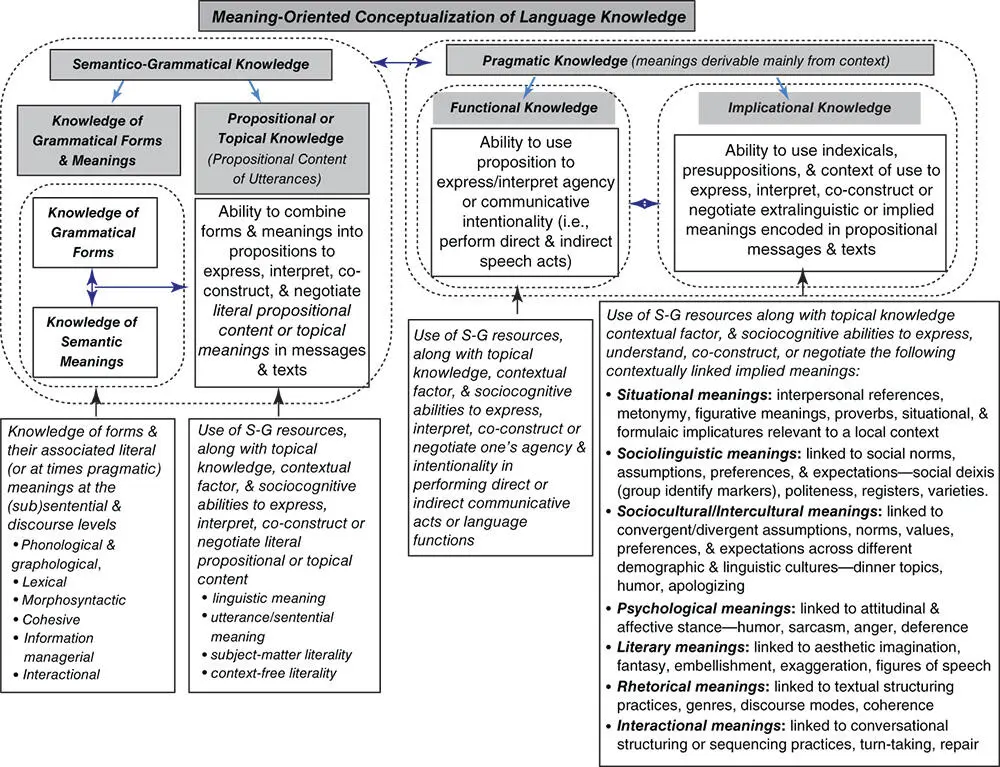

Figure 4 Semantico grammatical knowledge (adapted from Purpura, 2004, reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press through PLSclear, and Purpura, 2016, used with permission)

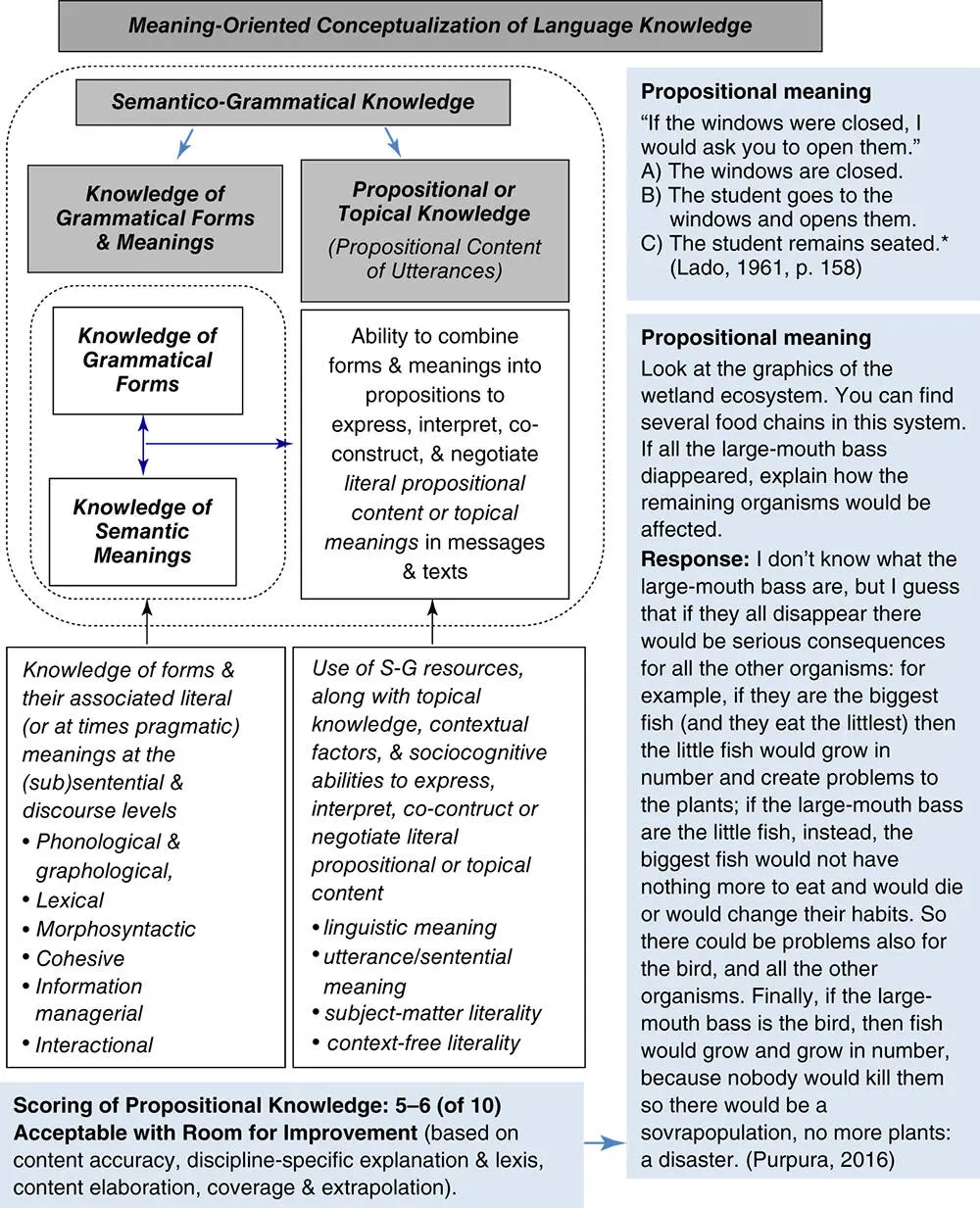

When grammatical forms combine with their individual meanings in a well‐formed utterance, they express a proposition (i.e., an idea, opinion, belief). This is referred to as the propositional (also, topical or content) meaning of an utterance. Propositional meaning is encoded in all utterances. An examinee draws on propositional or topical knowledge in LTM (long‐term memory) when she understands or expresses ideas. Thus, propositional or topical knowledge is intrinsically related to semantico‐grammatical ability and to L2 proficiency, since without propositional content, we would have language ability with nothing to say. Furthermore, it is unlikely that we could express well‐formed propositional content with no symbolic resources for expressing this content.

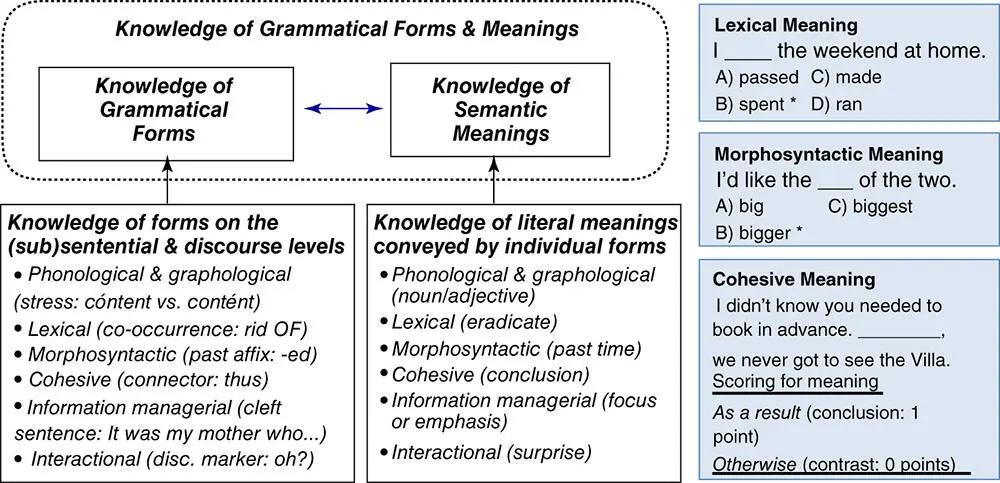

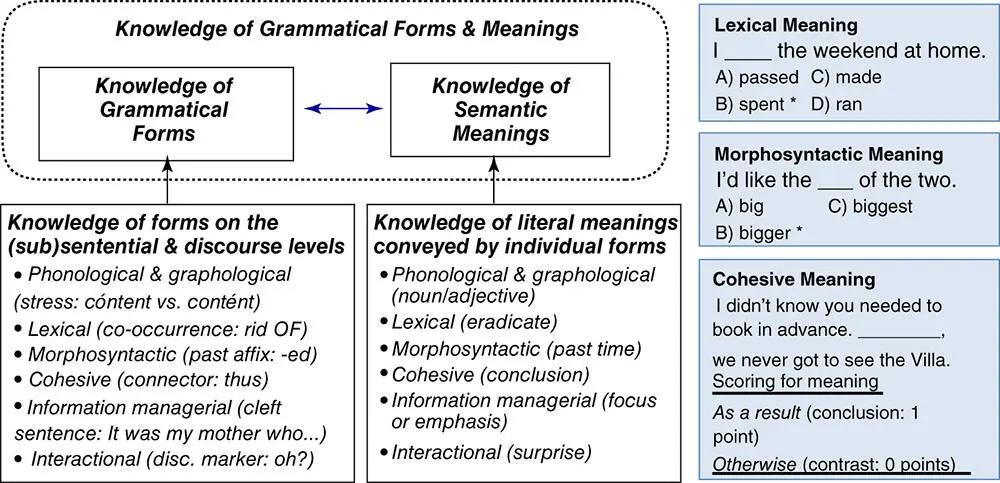

Moving beyond the semantic meaning of individual forms, language assessment focuses on the evaluation of one or more propositions in response data. However, given the long tradition of a form‐based approach to assessment, the scoring of utterances revolves mostly around the accuracy of the forms, rather than the quality or meaningfulness of the information expressed. To highlight the importance of propositional meaning as a resource for communication, Purpura (2016) extended the notion of semantico‐grammatical knowledge to include a propositional dimension. Figure 5presents a characterization of propositional knowledge, along with items typically used to measure this dimension.

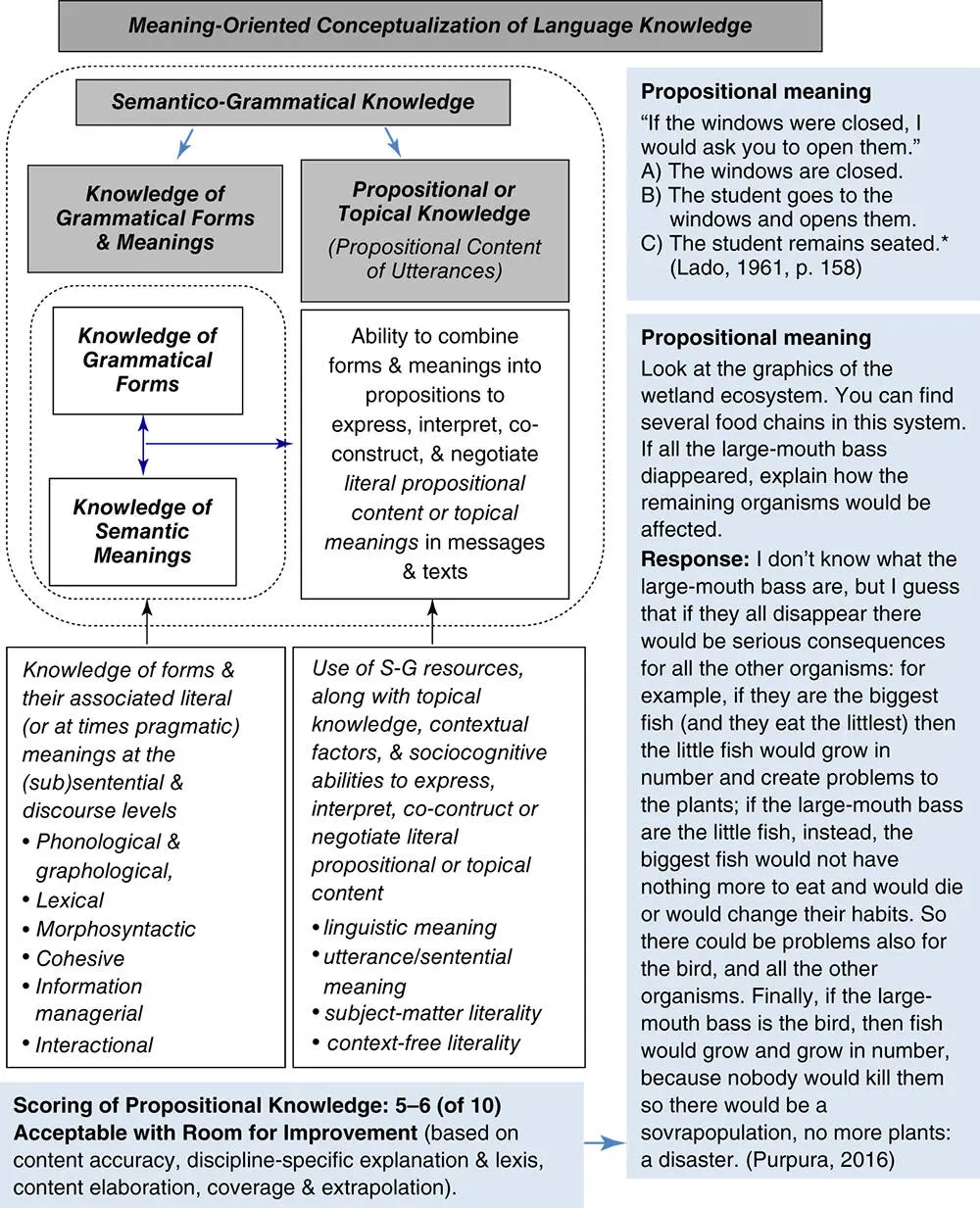

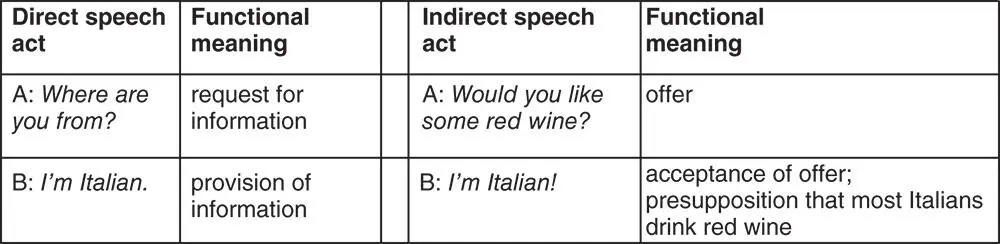

In many L2 assessments, examinees are expected to understand or express utterances with no reference to context beyond what is embodied in a sentence or two (see Figure 5). This aspect of semantics is referred to as the linguistic meaning of a sentence . In real‐life language use, however, language users have full access to the situational context. In these instances, they use semantico‐grammatical forms to understand and express utterances that carry propositional information within some goal‐oriented, interactional activity. The propositional content of the utterances comes from each interlocutor's topical knowledge in LTM (e.g., situational, interpersonal, transactional, experiential, autobiographical, imaginative, academic, or professional information). Interlocutors use these literal propositions not only to communicate topical content, but also to perform communicative acts or functions (e.g., to agree, complain) within the situation. In other words, examinees use functional knowledge to express language functions in context. Consider how the proposition I'm Italian is used to convey two contextualized language functions, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5 Extended model of semantico‐grammatical knowledge (adapted from Purpura, 2004, reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press through PLSclear, and Purpura, 2016, used with permission)

Figure 6 Speech acts and functional meaning

Figure 7 Meaning‐oriented model of L2 proficiency (adapted from Purpura, 2016, used with permission)

Semantico‐grammatical resources are used to form literal propositions, which embody a speaker's intended functional meaning (e.g., offer) within a communicative context. The literal and intended meaning of an utterance may have the same meaning (direct speech act) as the functional goal, or may differ significantly from the functional goal depending on context (indirect speech act). Finally, a well‐formed proposition can also be used to simultaneously encode a range of other meanings implied within the situational context. In the indirect speech act in Figure 6, the use of the expression I'm Italian to respond to an offer also encodes the sociocultural assumption that Italians like drinking red wine. The proposition in this context also encodes informality (sociolinguistic meanings) and even playfulness (psychological meanings). Purpura (2016) proposed a meaning‐oriented model of L2 knowledge that characterizes a learner's implicational knowledge as a pragmatic resource for understanding or expressing implied meanings derivable only from context ( Figure 7).

In sum, the ability to perform real‐world competencies depends on the learners' semantico‐grammatical knowledge and their ability to use context to accurately form utterances that communicate not only propositions, but also contextualized pragmatic meanings. From an assessment perspective, these components are all implicated in real‐life language use. However, depending on the purpose of the test, these components can also be measured separately (see Grabowski, 2009; Kim, 2009), especially when finer grained information is needed.

Measuring the Linguistic Resources of Communication

L2 educators have proposed three approaches to measuring the linguistic resources of communication. These include a trait/task‐based approach, a production features approach, and a developmental approach. The trait/task‐based approach can be based on a conception of L2 proficiency as a mental trait involving L2 knowledge, skills, and abilities, similar to those mentioned in the meaning‐oriented model of L2 knowledge. Alternatively, it can be based on the view that L2 proficiency is determined by the knowledge, skills, and abilities underlying task completion. Regardless of the basis for trait/task‐based approach, the assessment method includes a single task or a carefully sequenced set of tasks that allows test takers to display their receptive, emergent, or productive knowledge of the L2; the responses are then scored, mostly by human raters, using scoring rubrics.

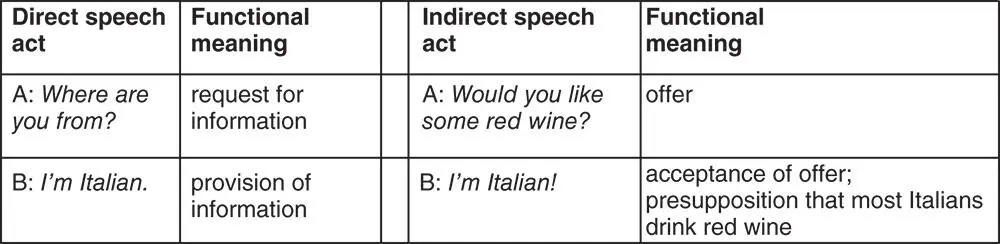

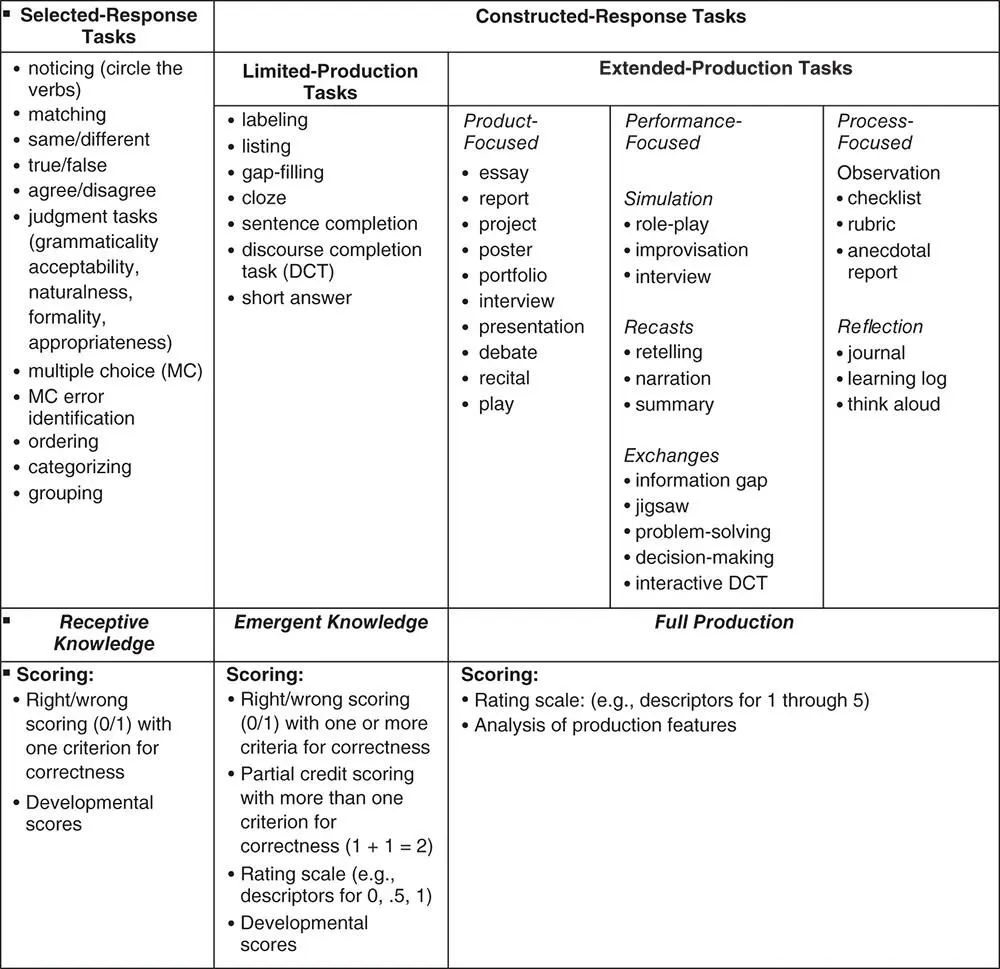

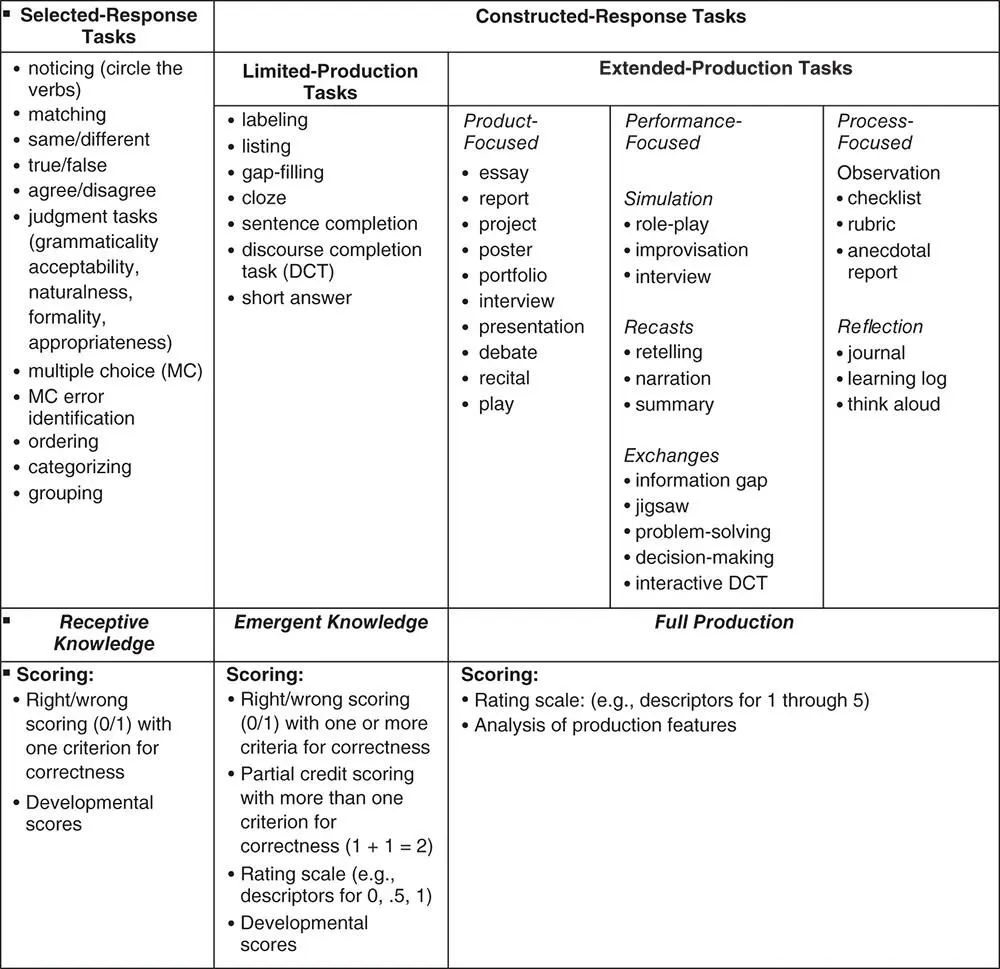

Assessment specialists have found it useful to categorize tasks according to the elicitation method (Bachman & Palmer, 2010) ( Figure 8). Selected‐response (SR) tasks present input in the form of an item, requiring examinees to choose the response from two or more options. These tasks aim to measure recognition or recall. While SR tasks are typically designed to measure one area of L2 knowledge, they may actually engage more than one (e.g., form and meaning). Constructed‐response tasks elicit L2 production. Limited‐production (LP) tasks present input in the form of an item, requiring examinees to produce anywhere from a single word to a sentence or two. These tasks aim to measure emergent production and are typically designed to measure one or more areas of knowledge. Extended‐production (EP) tasks present input in the form of a prompt, requiring examinees to produce language varying in quantity. EP tasks aim to measure full production, eliciting several areas of L2 knowledge simultaneously.

Figure 8 Task types and scoring (adapted from Purpura, 2004, reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press through PLSclear)

Читать дальше