1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...16 Hepatic N ‐acetylase displays genetic polymorphism. About 50% of the population acetylate isoniazid (an antitubercular drug) rapidly, whereas the other 50% acetylate it slowly. Slow acetylation is caused by an autosomal recessive gene that is associated with decreased hepatic N ‐acetylase activity. Slow acetylators are more likely to accumulate the drug and to experience adverse reactions.

Plasma pseudocholinesterase

Rarely, a deficiency (<1:2500) of this enzyme occurs and this extends the duration of action of suxamethonium (a frequently used neuromuscular blocking drug) from about 6 min to over 2 h or more.

In the elderly, hepatic metabolism of drugs may be reduced, but declining renal function is usually more important. By 65 years, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decreases by 30%, and every following year it falls a further 1–2% (as a result of cell loss and decreased renal blood flow). Thus, older people need smaller doses of many drugs than do younger persons, especially centrally acting drugs (e.g. opioids, benzodiazepines, antidepressants), to which the elderly seem to become more sensitive (by unknown changes in the brain). Hepatic microsomal enzymes and renal mechanisms are reduced at birth, especially in preterm babies. Both systems develop rapidly during the first 4 weeks of life. There are various methods for calculating paediatric doses (see British National Formulary ).

Metabolism and drug toxicity

Occasionally, reactive products of drug metabolism are toxic to various organs, especially the liver. Paracetamol , a widely used weak analgesic, normally undergoes glucuronidation and sulphation. However, these processes become saturated at high doses and the drug is then conjugated with glutathione. If the glutathione supply becomes depleted, then a reactive and potentially lethal hepatotoxic metabolite accumulates ( Chapter 46).

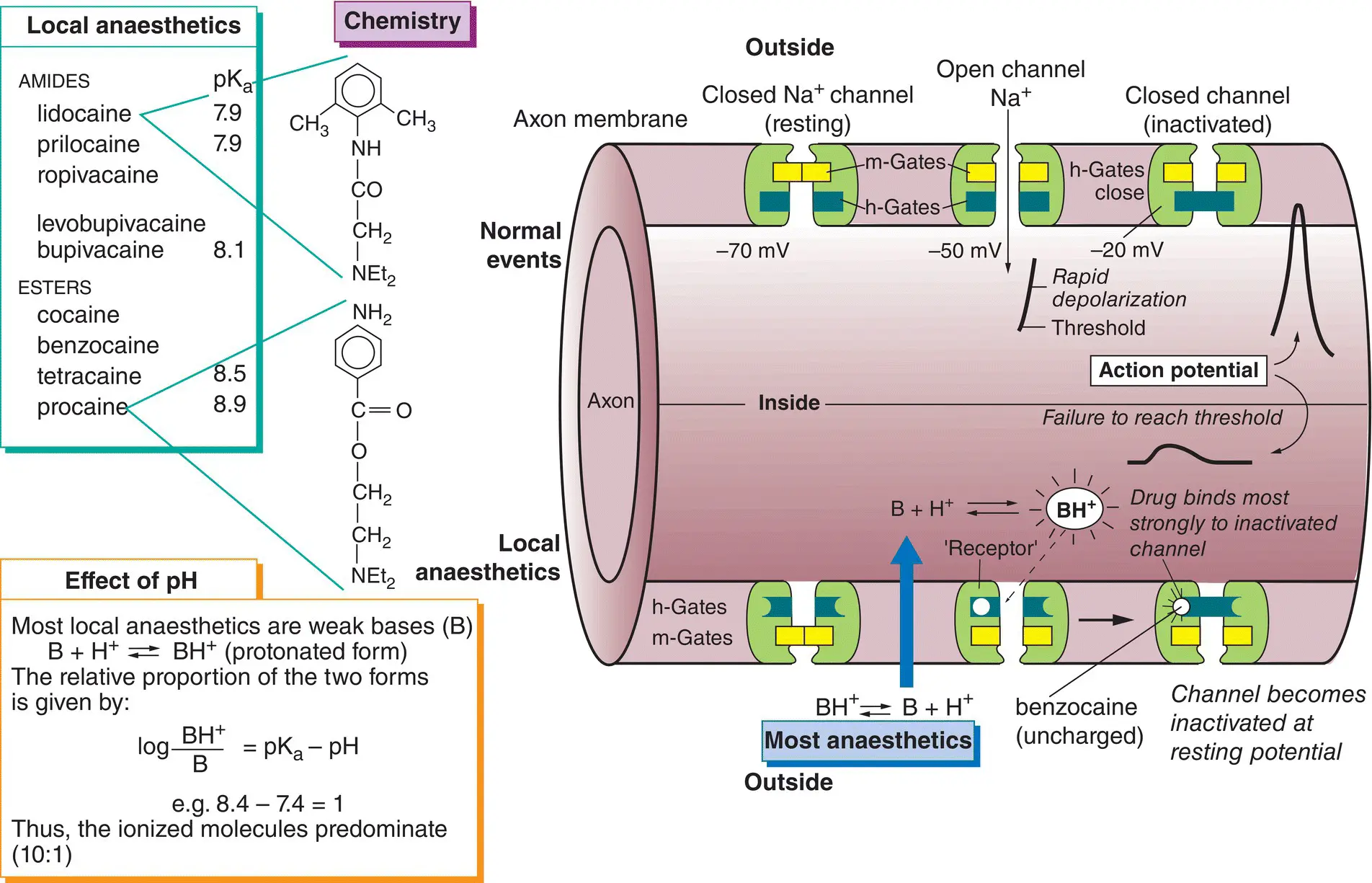

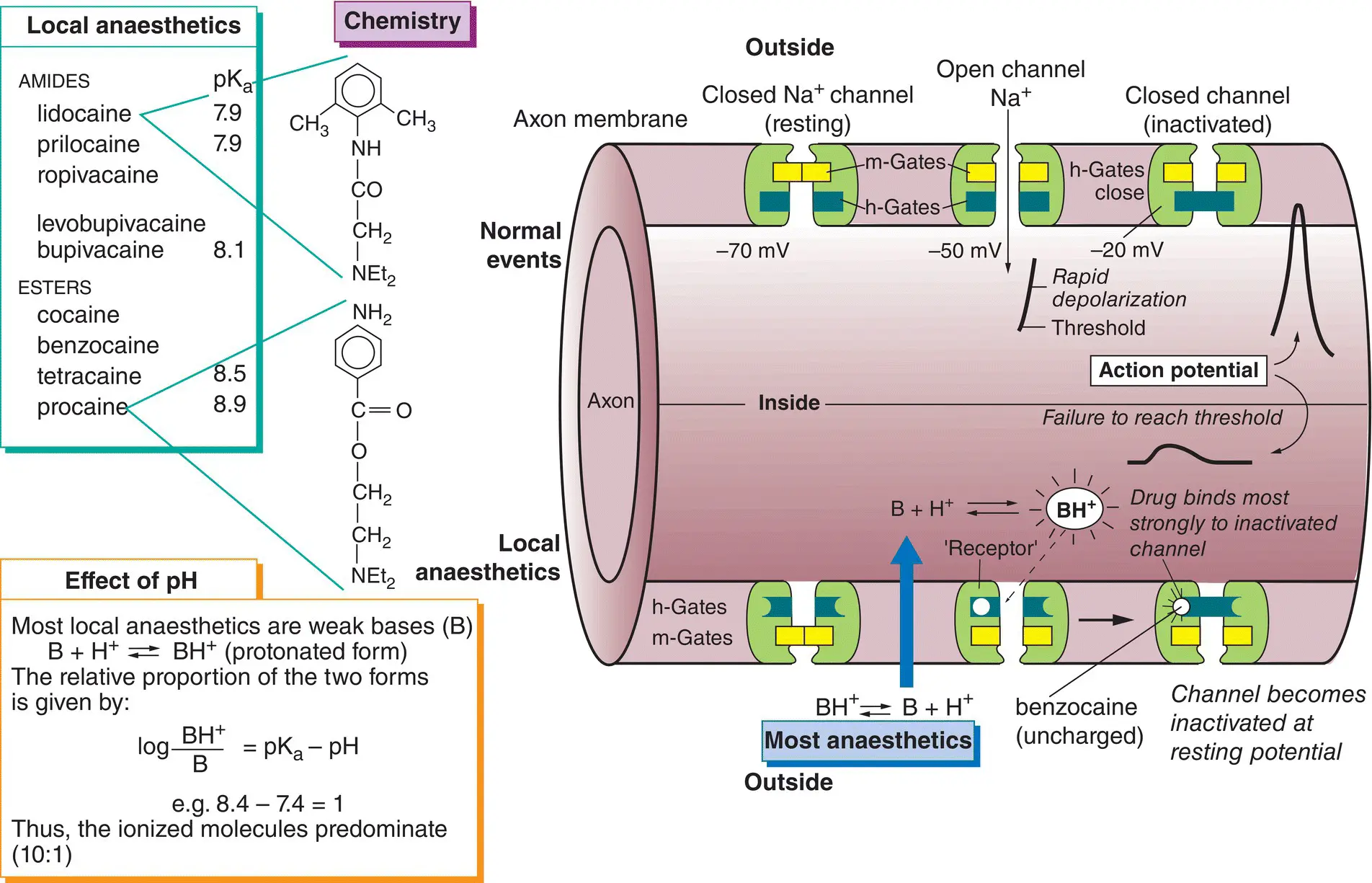

Local anaesthetics (top left) are drugs used to prevent pain by causing a reversible block of conduction along nerve fibres. Most are weak bases that exist mainly in a protonated form at body pH (bottom left). The drugs penetrate the nerve in a non‐ionized (lipophilic) form (  ) but, once inside the axon, some ionized molecules (

) but, once inside the axon, some ionized molecules (  ) are formed and these block the Na + channels(

) are formed and these block the Na + channels(  ) preventing the generation of action potentials(lower half of the figure).

) preventing the generation of action potentials(lower half of the figure).

All nerve fibres are sensitive to local anaesthetics but, in general, small‐diameter fibres are more sensitive than large fibres. Thus, a differential blockcan be achieved where the smaller pain and autonomic fibres are blocked, whereas coarse touch and movement fibres are spared. Local anaesthetics vary widely in their potency, duration of action, toxicity and ability to penetrate mucous membranes.

Local anaesthetics depress other excitable tissues (e.g. myocardium) if the concentration in the blood is sufficiently high, but their main unwanted systemic effects involve the central nervous system. Lidocaineis the most widely used agent. It acts more rapidly and is more stable than most other local anaesthetics. When given with epinephrine, its action lasts about 90 min. Prilocaineis similar to lidocaine, but is more extensively metabolized and is less toxic in equipotent doses. Bupivacainehas a slow onset (up to 30 min) but a very long duration of action, up to 8 h when used for nerve blocks. It is often used in pregnancy to produce continuous epidural blockade during labour. It is also the main drug used for spinal anaesthesia in the UK. The more toxic agents, tetracaineand cocaine, have restricted use. Cocaine is primarily used for surface anaesthesia where its intrinsic vasoconstrictor action is desirable (e.g. in the nose). Tetracaine drops are used in ophthalmology to anaesthetize the cornea, but less toxic drugs such as oxybuprocaineand proxymetacaine, which cause much less initial stinging, are better.

Hypersensitivity reactions may occur with local anaesthetics, especially in atopic patients, and more often with procaine and other esters of p ‐aminobenzoic acid.

Excitable tissues possess special voltage‐gated Na +channels that consist of one large glycoprotein α‐subunit and sometimes two smaller β‐subunits of unknown function. The α‐subunit has four identical domains, each containing six membrane‐spanning α‐helices (S1–S6). The 24 cylindrical helices are stacked together radially in the membrane to form a central channel. Exactly how voltage‐gated channels work is not known, but their conductance ( g Na +) is given by g Na +=  Na +m 3h, where

Na +m 3h, where  Na +is the maximum conductance possible, and m and h are gating constants that depend on the membrane potential. In the figure, these constants are shown schematically as physical gates within the channel. At the resting potential, most h‐gates (blue) are open and the m‐gates (yellow) are closed (closed channel). Depolarization causes the m‐gates to open (open channel), but the intense depolarization of the action potential then causes the h‐gates to close the channel (inactivation). This sequence is shown in the upper half of the figure (left to right). The m‐gate may correspond to the four positively charged S4 helices, which are thought to open the channel by moving outwards and rotating in response to membrane depolarization. The h‐gate responsible for inactivation may be the intracellular loop connecting the S3 and S5 helices; this swings into the internal mouth of the channel and closes it.

Na +is the maximum conductance possible, and m and h are gating constants that depend on the membrane potential. In the figure, these constants are shown schematically as physical gates within the channel. At the resting potential, most h‐gates (blue) are open and the m‐gates (yellow) are closed (closed channel). Depolarization causes the m‐gates to open (open channel), but the intense depolarization of the action potential then causes the h‐gates to close the channel (inactivation). This sequence is shown in the upper half of the figure (left to right). The m‐gate may correspond to the four positively charged S4 helices, which are thought to open the channel by moving outwards and rotating in response to membrane depolarization. The h‐gate responsible for inactivation may be the intracellular loop connecting the S3 and S5 helices; this swings into the internal mouth of the channel and closes it.

If enough Na +channels are opened, then the rate of Na +entry into the axon exceeds the rate of K +exit, and at this point, the threshold potential, entry of Na +ions further depolarizes the membrane. This opens more Na +channels, resulting in further depolarization, which opens more Na +channels, and so on. The fast inward Na +current quickly depolarizes the membrane towards the Na +equilibrium potential (around +67 mV). Then, inactivation of the Na +channels and the continuing efflux of K +ions cause repolarization of the membrane. Finally, the Na +channels regain their normal ‘excitable’ state and the Na +pump restores the lost K +and removes the gained Na +ions.

Mechanism of local anaesthetics

Local anaesthetics penetrate into the interior of the axon in the form of the lipid‐soluble free base. There, protonated molecules are formed, which then enter and plug the Na +channels after binding to a ‘ receptor ’ (residues of the S6 transmembrane helix). Thus, quaternary (fully protonated) local anaesthetics work only if they are injected inside the nerve axon. Uncharged agents (e.g. benzocaine) dissolve in the membrane, but the channels are blocked in an all‐or‐none manner. Thus, ionized and non‐ionized molecules act in essentially the same way (i.e. by binding to a ‘receptor’ on the Na +channel). This ‘blocks’ the channel, largely by preventing the opening of h‐gates (i.e. by increasing inactivation). Eventually, so many channels are inactivated that their number falls below the minimum necessary for depolarization to reach threshold and, because action potentials cannot be generated, nerve block occurs. Local anaesthetics are ‘use dependent’ (i.e. the degree of block is proportional to the rate of nerve stimulation). This indicates that more drug molecules (in their protonated form) enter the Na +channels when they are open and cause more inactivation.

Читать дальше

) but, once inside the axon, some ionized molecules (

) but, once inside the axon, some ionized molecules (  ) are formed and these block the Na + channels(

) are formed and these block the Na + channels(  ) preventing the generation of action potentials(lower half of the figure).

) preventing the generation of action potentials(lower half of the figure). Na +m 3h, where

Na +m 3h, where  Na +is the maximum conductance possible, and m and h are gating constants that depend on the membrane potential. In the figure, these constants are shown schematically as physical gates within the channel. At the resting potential, most h‐gates (blue) are open and the m‐gates (yellow) are closed (closed channel). Depolarization causes the m‐gates to open (open channel), but the intense depolarization of the action potential then causes the h‐gates to close the channel (inactivation). This sequence is shown in the upper half of the figure (left to right). The m‐gate may correspond to the four positively charged S4 helices, which are thought to open the channel by moving outwards and rotating in response to membrane depolarization. The h‐gate responsible for inactivation may be the intracellular loop connecting the S3 and S5 helices; this swings into the internal mouth of the channel and closes it.

Na +is the maximum conductance possible, and m and h are gating constants that depend on the membrane potential. In the figure, these constants are shown schematically as physical gates within the channel. At the resting potential, most h‐gates (blue) are open and the m‐gates (yellow) are closed (closed channel). Depolarization causes the m‐gates to open (open channel), but the intense depolarization of the action potential then causes the h‐gates to close the channel (inactivation). This sequence is shown in the upper half of the figure (left to right). The m‐gate may correspond to the four positively charged S4 helices, which are thought to open the channel by moving outwards and rotating in response to membrane depolarization. The h‐gate responsible for inactivation may be the intracellular loop connecting the S3 and S5 helices; this swings into the internal mouth of the channel and closes it.