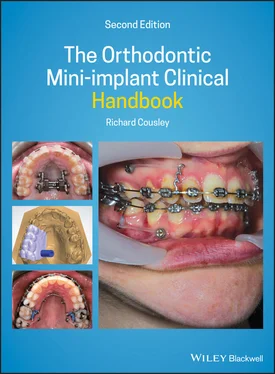

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data

Names: Cousley, Richard, author.

Title: The orthodontic mini‐implant clinical handbook / Richard Cousley.

Description: Second edition. | Hoboken, NJ : Wiley‐Blackwell, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019045151 (print) | LCCN 2019045152 (ebook) | ISBN 9781119509752 (hardback) | ISBN 9781119509721 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781119509745 (epub)

Subjects: MESH: Orthodontic Anchorage Procedures | Dental Implantation | Dental Implants | Miniaturization

Classification: LCC RK667.I45 (print) | LCC RK667.I45 (ebook) | NLM WU 400 | DDC 617.6/93–dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019045151LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019045152

Cover Design: Wiley

Cover Images: Courtesy of Richard Cousley

Preface to Second Edition

In some respects, it seems relatively early for a second edition to be published seven years after the first one. However, the subject of mini‐implants in orthodontics is a dynamic and rapidly evolving field in terms of research publications, clinical techniques, collective comprehension and clinical insight. Some of these refinements appear subtle, but nevertheless represent clinically significant refinements in both our comprehension and applications. Therefore, this second edition has arisen from the realisation that both experienced orthodontists and those new to mini‐implant anchorage will benefit from an updated appraisal of this progressive field and its ever‐increasing applications in clinical orthodontics.

For example, our understanding of the nature of three‐dimensional control of target tooth movements has greatly increased in the last 10 years. This has resulted from the initial recognition and then comprehension of biomechanical side‐effects observed during the early years of mini‐implant usage (and described in Chapter 1). This increased understanding has been matched with the introduction of relatively simple but effective clinical adjuncts such as powerarms (as described in Chapters 7and 9). These have greatly enhanced our biomechanical control of anterior and posterior tooth movements. Consequently, we are now much more able to control not only anchorage but the delivery of bodily tooth movements in all three dimensions. However, it is important to acknowledge that mini‐implants do not provide ‘miracle’ solutions since orthodontics still has to overcome biological limitations such as the severe alveolar bone deficiencies in hypodontia cases (discussed in Chapter 9).

Over the last 10 years, existing clinical techniques have been refined, and become more standardised and evidence based, as exemplified by protocols for molar intrusion in the treatment of anterior openbites ( Chapter 10). The outer envelope of achievable orthodontic treatments has also been further expanded. This is amply illustrated by the inclusion of a new chapter in this edition on mini‐implanted anchored maxillary expansion ( Chapter 13). Last, but not least, orthodontic diagnostic imaging options have changed dramatically in recent years with the dissemination of lower dose cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) machines and software. This has had a positive impact on the use of mini‐implants with the introduction of 3D imaging and planning techniques (described in Chapter 5).

However, one key theme has been continued from the first edition. The second edition still provides a combination of pragmatic clinical advice on common orthodontic clinical problems, based on a synthesis of the literature evidence base, judgement, experience and clinical insight. Therefore, I hope that you enjoy reading this textbook and that I have done service to my orthodontic peers and, indeed, to Sir Isaac Newton, the physics‐based father of anchorage concepts.

Richard Cousley

2019

1 Orthodontic Mini‐implant Principles and Potential Complications

This chapter could alternatively have been titled ‘the advantages and disadvantages’ or, more trendily, ‘the pros and cons’ of mini‐implants, since it describes what we have to gain and possibly lose from their use. However, before we embark on these details, it's important to summarise what is meant by orthodontic mini‐implants and how we’ve arrived at current clinical applications.

1.1 The Origins of Orthodontic Bone Anchorage

Orthodontic‐specific skeletal fixtures were developed from two distinct sources:

restorative implants

maxillofacial surgical plating kits [1].

Orthodontic implants were first produced in the 1990s by modification of dental implant designs, making them shorter (e.g. 4–6 mm length) and wider (e.g. 3 mm diameter). However, they retained the crucial requirement for osseointegration, which is a direct structural and functional union of bone with the implant surface causing clinical ankylosis of the fixture. In contrast, orthodontic miniplates and mini‐implants (miniscrews) are derived from bone fixation technology, and primarily rely on mechanical retention rather than osseointegration. In effect, modification of the maxillofacial bone plate design, adding a transmucosal neck and intraoral head, resulted in the miniplate, whilst adaption of the fixation screw design produced the mini‐implant. Since the start of this millennium, a wide variety of customised orthodontic mini‐implants have been produced and these are now used in the vast majority of orthodontic bone anchorage applications. Orthodontic implants are no longer in standard use and the invasive nature of miniplates tends to limit their use to orthopaedic traction (e.g. Class III) cases or occasionally where the alveolar and palatal sites are too limited for mini‐implant usage (as exemplified in Chapter 8).

1.2 The Evolution of Mini‐implant Biomechanics

Hindsight is a wonderful tool, especially with new treatment modalities such as orthodontic mini‐implants. Much has changed in my clinical practice since I first used mini‐implants, back in 2003. And when one looks at the early texts on mini‐implants (including the first edition of this textbook), the evolution of techniques is also very apparent. The mini‐implant evolution in the 10 years from circa 2005 to 2015 may be best summarised as shown in Table 1.1.

1.3 3D Anchorage Indications

This gradual refinement of mini‐implant techniques has been accompanied by a substantial increase in the range of clinical applications for mini‐implants. The proportion of these uses will vary between orthodontists, depending on their individual caseloads, and even on financial and cultural influences. Overall, it's best to subdivide modern anchorage control according to each of the three dimensions and ‘other’ applications, with common examples for each category listed below.

| Anchorage dimension |

|

| Anteroposterior |

Incisor retraction and torqueMolar distalisationMolar advancement |

| Vertical |

Single/multiple teeth intrusionTooth extrusion |

| Transverse |

Centreline correctionsAltering occlusal planeRapid maxillary expansion (RME) |

| Other |

Intermaxillary fixation (IMF) and tractionTemporary dental restorative abutment |

Table 1.1 The clinical evolution of orthodontic mini‐implant anchorage is subdivided into three chronological stages, with a description of the main focus at each stage along with representative clinical examples and associated side‐effects

| Stage of evolution |

Clinical focus |

Technique examples |

Side‐effects |

| 1 |

Reliable anchorage |

Direct anchorage, from alveolar sites Indirect anchorage, especially palatal sites |

Vertical effects of oblique traction, e.g. lateral openbites and uncontrolled incisor movements Hidden anchorage loss due to failings of connecting anchorage components |

| 2 |

Minimised side‐effects |

Traction powerarms Rigid transpalatal auxiliaries |

Prevention of incisor extrusion/retroclination Prevention of molar buccal/palatal tipping movements during intrusion |

| 3 |

Optimised target tooth movements (in addition to anchorage control) |

Controlled 3D tooth movements during:incisor retractionmolar distalisationmolar intrusion |

Bodily movement of target teeth, e.g.torque control during incisor retraction, bodily distalisation of molars, vertical molar intrusion movements |

1.4 Using the Right Terminology

Читать дальше