The Decimaldata type is unusual because you can't declare it. In fact, it is a subtype of a variant. You need to use the VBA CDecfunction to convert a variant to the Decimaldata type.

Generally, it's best to use the data type that uses the smallest number of bytes yet still can handle all the data that will be assigned to it. When VBA works with data, execution speed is partially a function of the number of bytes that VBA has at its disposal. In other words, the fewer the bytes used by the data, the faster that VBA can access and manipulate the data.

For worksheet calculation, Excel uses the Doubledata type, so that's a good choice for processing numbers in VBA when you don't want to lose any precision. For integer calculations, you can use the Integertype (which is limited to values less than or equal to 32,767). Otherwise, use the Longdata type. In fact, using the Longdata type even for values less than 32,767 is recommended because this data type may be a bit faster than using the Integertype. When dealing with Excel worksheet row numbers, you want to use the Longdata type because the number of rows in a worksheet exceeds the maximum value for the Integerdata type.

If you don't declare the data type for a variable that you use in a VBA routine, VBA uses the default data type, Variant. Data stored as a Variantacts like a chameleon: it changes type, depending on what you do with it.

The following procedure demonstrates how a variable can assume different data types:

Sub VariantDemo() MyVar = True MyVar = MyVar * 100 MyVar = MyVar / 4 MyVar = "Answer: " & MyVar MsgBox MyVar End Sub

In the VariantDemoprocedure, MyVarstarts as a Boolean. The multiplication operation converts it to an Integer. The division operation converts it to a Double. Finally, it's concatenated with text to make it a String. The MsgBoxstatement displays the final string: Answer: -25.

To demonstrate further the potential problems in dealing with Variantdata types, try executing this procedure:

Sub VariantDemo2() MyVar = "123" MyVar = MyVar + MyVar MyVar = "Answer: " & MyVar MsgBox MyVar End Sub

The message box displays Answer: 123123. This is probably not what you wanted. When dealing with variants that contain text strings, the +operator will join (concatenate) the strings together rather than perform addition.

You can use the VBA TypeNamefunction to determine the data type of a variable. Here's a modified version of the VariantDemoprocedure. This version displays the data type of MyVarat each step.

Sub VariantDemo3() MyVar = True MsgBox TypeName(MyVar) MyVar = MyVar * 100 MsgBox TypeName(MyVar) MyVar = MyVar / 4 MsgBox TypeName(MyVar) MyVar = "Answer: " & MyVar MsgBox TypeName(MyVar) MsgBox MyVar End Sub

Thanks to VBA, the data type conversion of undeclared variables is automatic. This process may seem like an easy way out, but remember that you sacrifice speed and memory—and you run the risk of errors that you may not even know about.

Declaring each variable in a procedure before you use it is an excellent habit. Declaring a variable tells VBA its name and data type. Declaring variables provides two main benefits.

Your programs run faster and use memory more efficiently. The default data type, Variant, causes VBA to perform time-consuming checks repeatedly and reserve more memory than necessary. If VBA knows the data type, it doesn't have to investigate, and it can reserve just enough memory to store the data.

You avoid problems involving misspelled variable names. This benefit assumes that you use Option Explicit to force yourself to declare all variables (see the next section). Say that you use an undeclared variable named CurrentRate. At some point in your routine, however, you insert the statement CurentRate = .075. This misspelled variable name, which is difficult to spot, will likely cause your routine to give incorrect results.

Forcing yourself to declare all variables

To force yourself to declare all the variables that you use, include the following as the first instruction in your VBA module:

Option Explicit

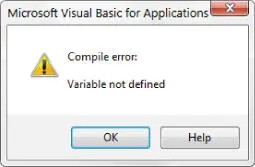

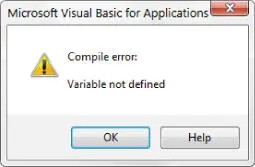

When this statement is present, VBA won't even execute a procedure if it contains an undeclared variable name. VBA issues the error message shown in Figure 3.1, and you must declare the variable before you can proceed.

FIGURE 3.1 VBA's way of telling you that your procedure contains an undeclared variable

To ensure that the Option Explicitstatement is inserted automatically whenever you insert a new VBA module, enable the Require Variable Declaration option on the Editor tab of the VBE Options dialog box (choose Tools ➪ Options). It is generally considered a best practice to enable this option. Be aware, however, that this option will not affect existing modules; the option affects only those modules created after it is enabled.

A variable's scope determines in which modules and procedures you can use the variable. Table 3.2lists the three ways in which a variable can be scoped.

TABLE 3.2 Variable Scope

| Scope |

To Declare a Variable with This Scope |

| Single procedure |

Include a Dimor Staticstatement within the procedure. |

| Single module |

Include a Dimor Privatestatement before the first procedure in a module. |

| All modules |

Include a Publicstatement before the first procedure in a module. |

We discuss each scope further in the following sections.

A note about the examples in this chapter

This chapter contains many examples of VBA code, usually presented in the form of simple procedures. These examples demonstrate various concepts as simply as possible. Most of these examples don't perform any particularly useful task; in fact, the task can often be performed in a different (perhaps more efficient) way. In other words, don't use these examples in your own work. Subsequent chapters provide many more code examples that are useful.

A local variable is one declared within a procedure. You can use local variables only in the procedure in which they're declared. When the procedure ends, the variable no longer exists, and Excel frees up the memory that the variable used. If you need the variable to retain its value when the procedure ends, declare it as a Staticvariable. (See the section “Static variables” later in this chapter.)

The most common way to declare a local variable is to place a Dimstatement between a Substatement and an End Substatement. Dimstatements usually are placed right after the Substatement, before the procedure's code.

Dimis a shortened form of Dimension . In old versions of BASIC, this statement was used exclusively to declare the dimensions for an array. In VBA, the Dimkeyword is used to declare any variable, not just arrays.

Читать дальше