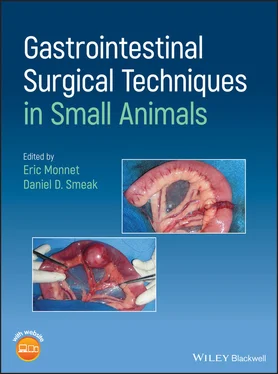

Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Describes techniques for canine and feline gastrointestinal surgery in detail Presents the state of the art for GI surgery in dogs and cats Includes access to a companion website with video clips demonstrating techniques

is an essential resource for small animal surgeons and veterinary residents.

Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

22 Jiborn, H. et al. (1978c). Healing of experimental colonic anastomoses. The effect of suture technic on collagen concentration in the colonic wall. Am. J. Surg. 135 (3): 333–340.

23 Jonsson, T. and Hogstrom, H. (1992). Effect of suture technique on early healing of intestinal anastomoses in rats. Eur. J. Surg. 158 (5): 267–270.

24 Jonsson, K. et al. (1985). Comparison of healing in the left colon and ileum. Changes in collagen content and collagen synthesis in the intestinal wall after ileal and colonic anastomoses in the rat. Acta Chir. Scand. 151 (6): 537–541.

25 Maney, J.W. et al. (1988). Biofragmentable bowel anastomosis ring: comparative efficacy studies in dogs. Surgery 103 (1): 56–62.

26 Marks, S.L. (2013). Enteral and parenteral nutrition. In: Canine and Feline Gastroenterology (eds. R.J. Washabau and M.J. Day), 429–444. St Louis: Elsevier.

27 Masini, B.D. et al. (2011). Bacterial adherence to suture materials. J. Surg. Educ. 68 (2): 101–104.

28 Mastboom, W.J. et al. (1991a). Influence of methylprednisolone on the healing of intestinal anastomoses in rats. Br. J. Surg. 78 (1): 54–56.

29 Mastboom, W.J. et al. (1991b). The influence of NSAIDs on experimental intestinal anastomoses. Dis. Colon Rectum 34 (3): 236–243.

30 Muftuoglu, M.A. et al. (2005). Effects of high bilirubin levels on the healing of intestinal anastomosis. Surg. Today 35 (9): 739–743.

31 Munireddy, S. et al. (2010). Intra‐abdominal healing: gastrointestinal tract and adhesions. Surg. Clin. North Am. 90 (6): 1227–1236.

32 Pascoe, J.R. and Peterson, P.R. (1989). Intestinal healing and methods of anastomosis. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract. 5 (2): 309–333.

33 Ryan, S. et al. (2006). Comparison of biofragmentable anastomosis ring and sutured anastomoses for subtotal colectomy in cats with idiopathic megacolon. Vet. Surg. 35 (8): 740–748.

34 Shikata, J. et al. (1982). The effect of local blood flow on the healing of experimental intestinal anastomoses. Surg Gynecol. Obstet. 154 (5): 657–661.

35 Snowdon, K.A. et al. (2016). Risk factors for dehiscence of stapled functional end‐to‐end intestinal anastomoses in dogs: 53 cases (2001–2012). Vet. Surg. 45 (1): 91–99.

36 Thompson, S.K. et al. (2006). Clinical review: healing in gastrointestinal anastomoses, part I. Microsurgery 26 (3): 131–136.

37 Thornton, F.J. and Barbul, A. (1997). Healing in the gastrointestinal tract. Surg. Clin. North Am. 77 (3): 549–573.

38 Verhofstad, M.H. and Hendriks, T. (1994). Diabetes impairs the development of early strength, but not the accumulation of collagen, during intestinal anastomotic healing in the rat. Br. J. Surg. 81 (7): 1040–1045.

39 Williams, J.M. (2012). Colon. In: Veterinary Surgery Small Animal, 2e (eds. K.M. Tobias and S.A. Johnston), 1542–1563. St Louis: Elsevier.

2 Suture Materials, Staplers, and Tissue Apposition Devices

Daniel D. Smeak

Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Suture remains the most common means of achieving apposition of wound edges to promote optimal healing (Booth 2003, Smeak 1998). Ideally, sutures should provide support until the repair has regained sufficient strength to withstand tensile forces. When this has been achieved, the suture material should ideally disintegrate in a predictable fashion to prevent further tissue reaction and inhibition of wound healing. Sutures should not create undue tissue reaction because inflammation can prolong the lag phase of wound healing, and delay return to strength. In general, monofilament and synthetic nonabsorbable sutures induce the least amount of tissue reaction, whereas multifilament sutures that are made from natural materials such as silk or chromic catgut are some of the most reactive suture materials. Monofilament absorbable suture materials are often the first choice for surgeons because they are relatively inert and have good to excellent tensile strength, and most have very predictable absorption profiles when exposed to contamination and variable pH environments. Multifilament suture materials have been used successfully in a variety of visceral repairs, however, because most have inherent capillarity (or the drawing up of fluid between the fine woven strands of suture) and high affinity for bacterial adherence, these sutures have fallen out of favor (Chih‐Chang and William 1984). Wicking up of contaminated fluid into multifilament suture filaments from the lumen of hollow organs can contribute to increased tissue reaction, and the bacterial load within the material may be difficult to clear by normal host defenses. For these reasons and others mentioned later, monofilament absorbable sutures are favored and are now used more often in oral and gastrointestinal surgeries.

It should be emphasized that the surgeon's technique (the manner of needle and suture placement, and tissue handling) likely has a greater influence on the generation of tissue inflammation at the repair site than the choice of suture material used in the repair. Needles should be carefully introduced and removed from the tissue “along the curve of the needle” to reduce tissue damage and minimize the size of the needle “track.” Tissue should be well‐apposed with suture without being crushed and handled atraumatically if instruments are required. Forcibly tied sutures and aggressive instrument handling cause tissue damage that impedes healing and inhibits proliferation of new blood vessels, increasing the risk of repair dehiscence (Hoer et al. 2001).

2.1 Suture Materials

Sutures are classified as absorbable or nonabsorbable, and monofilament or multifilament ( Table 2.1). Absorbable sutures are desirable in gastrointestinal surgery since they eventually are degraded and removed by the body over days to months. Nonabsorbable sutures do not lose significant strength over 60 days, and remain in the tissues to some degree for years. Monofilament sutures are composed of a single smooth strand, whereas multifilament sutures are braided or woven from multiple strands.

Suture is selected for a specific digestive organ wound repair considering the physical characteristics of the suture material (tensile strength and knot security, absorption rate, surface qualities, capillarity, tissue reactivity), and the environment and healing rate of the tissue involved in the repair. As a rule, more pliable and smaller diameter sutures have favorable handling properties in gastrointestinal surgery compared to larger, stiffer suture materials.

Table 2.1 Characteristics of suture materials used in digestive system procedures.

| Absorbable Suture | Nonabsorbable Suture | Trade Name | Type | Degradation Process | Foreign Body Response | Tensile Strength Retention (%) | Relative Knot Security | Mass Absorption Time (days) | Comments |

| Chromic Catgut | Surgical gut; chromic gut | Rapid to Intermediate absorbable multifilament | Phagocytosis and proteolytic enzymes | Moderate | Unpredictable | Fair | Variable; 45–60 d or longer | Degradation and tissue reactivity related to where implanted; knots imbibe fluid and unravel if knot ears are cut short | |

| Polyglactin 910 | Vicryl Rapide | Rapid absorbable multifilament | Hydrolysis | Mild | 50% after 5 d; 0% after 14 d | Fair to good | 42 | Irradiated to aid in dissolving | |

| Vicryl, Coated Vicryl Plus | Intermediate absorbable multifilament | Hydrolysis | Mild | 75% after 14 d; 50% after 21 d | Fair to good | 56–70 | Plus designates triclosan (antibacterial) impregnated | ||

| Lactomer | Polysorb (coated) | Intermediate absorbable multifilament | Hydrolysis | Mild | 80% after 14 d; 30% after 21 d | Fair to good | 56–70 | Improvements in braid construction and coating reduce drag and improve knot security | |

| Velosorb (coated) | Rapid absorbable multifilament | Hydrolysis | Mild | 60% at 5 d; 0% at 14 d | Fair to good | 40–50 | Irradiated to aid in dissolving; similar to Vicryl Rapide | ||

| Polyglycolic Acid | Dexon S (uncoated), Dexon II (coated) | Intermediate absorbable multifilament | Hydrolysis | Mild | 65% after 14 d; 35% after 21 d | Fair to good | 60–90 | Coated Dexon II helps reduce drag, but decreases knot security | |

| Polyglytone 6211 | Caprosyn | Rapid to intermediate absorbable monofilament | Hydrolysis | Minimal | 60% after 5 d; 20–30% after 10 d | Fair | 56 | Knots have been known to untie spontaneously when incubated in serum; supple easy to handle for monofilament; fastest mass absorption of absorbable monofilaments | |

| Polygliocaprone 25 | Monocryl | Rapid to intermediate absorbable monofilament | Hydrolysis | Minimal | 50–60% after 7 d; 20–30% after 14 d; 0% after 21 d | Good | 91–119 | Supple easy to handle for monofilament. | |

| Polyglycolic Acid/Polycaprolactone | Quill Monoderm | Intermediate absorbable monofilament barbed | Hydrolysis | Slight | 42–76% at 7 d; 36–52% at 14 d | N/A | 90–120 | Uni‐ and bidirectional barbed suture; choose one size larger due to strength loss from barbs. Slightly higher tissue reaction than V‐Loc 90. | |

| Stratafix PGA‐PCL Plus (barbed) | Rapid to intermediate absorbable monofilament barbed | Hydrolysis | Minimal | 50–60% after 7 d; 20–30% after 14 d; 0% after 21 d | N/A | 90–120 | Stratafix Monocryl comes with spiral barbs; uni‐ or bidirectional. Plus – antibacterial | ||

| Glycomer 631 | Biosyn | Intermediate absorbable monofilament | Hydrolysis | Minimal | 75% after 14 d; 40% after 21 d | Average | 110 | Knots occasionally untie spontaneously | |

| V‐Loc 90 | Intermediate absorbable monofilament barbed | Hydrolysis | Minimal | 90% at 7 d; 75% at 14 d | N/A | 90 | Unidirectional barbed suture; equivalent to strength of suture one size smaller – choose size as you would conventional suture | ||

| Polyglyconate | Maxon | Prolonged absorbable monofilament | Hydrolysis | Minimal | 81% after 14 d; 59% after 28 d; 30% after 42 d | Good | 180 | Similar to PDS II; tends to have slightly more memory in larger sizes | |

| Polydioxanone | PDS II; PDS Plus | Prolonged absorbable monofilament | Hydrolysis | Minimal | 74% after 14 d; 58% after 28 d; 41% after 42 d | Good | 180 | Plus designates triclosan (antibacterial) impregnated | |

| V‐Loc 180 | Prolonged absorbable monofilament barbed | Hydrolysis | Negligible | 80% at 7 d; 75% at 14 d; 65% at 21 d | N/A | 180 | Unidirectional barbed suture; equivalent to strength of suture one size smaller‐choose size as you would conventional suture. | ||

| Stratafix PDO, PDO Plus | Prolonged absorbable monofilament barbed | Hydrolysis | Negligible | 80% at 7 d; 75% at 14 d; 65% at 21 d | N/A | 120–180 | Stratafix comes in uni‐ and bidirectional strands with symmetrical or spiral barbs. Symmetrical unidirectional barbed sutures are recommended for high tension repairs. PDS plus is antibacterial | ||

| Quill PDO | Prolonged absorbable monofilament barbed | Hydrolysis | Negligible | 67–80% at 14 d; 50–80% at 28 d | N/A | 180 | Uni‐ and bidirectional barbed suture; choose one size larger due to strength loss from barbs | ||

| Polyamide | Ethilon; Dermalon; Surgilon | Nonabsorbable monofilament | N/A | Minimal | 15–20% loss in 365 d; retains 80% indefinitely | Fair | N/A | Slowly loses strength over years by process of hydrolysis | |

| Nurolon | Nonabsorbable multifilament | N/A | Minimal | 15–20% loss in 365 d; retains 80% indefinitely | Fair | N/A | Slowly loses strength over years by process of hydrolysis | ||

| Quill Nylon | Nonabsorbable monofilament barbed | N/A | Minimal | Similar to conventional nylon | N/A | N/A | Similar to conventional nylon | ||

| Polybutester | Novafil | Nonabsorbable monofilament | N/A | Negligible | N/A | Good | N/A | Handles well for monofilament; stretchy | |

| V‐Loc PBT | Nonabsorbable monofilament barbed | N/A | Negligible | N/A | N/A | N/A | Unidirectional barbed suture; permanent soft tissue approximation; equivalent to strength of suture one size smaller – choose size as you would conventional suture | ||

| Polypropylene | Prolene; Surgipro; Surgipro II | Nonabsorbable monofilament | N/A | Negligible | N/A | Good | N/A | Does not lose appreciable strength over long periods of time; one of most inert suture besides steel | |

| Quill Polypropylene | Nonabsorbable monofilament barbed | N/A | Negligible | N/A | N/A | N/A | Uni‐ and bidirectional barbed suture; choose one size larger due to strength loss from barbs | ||

| Stratafix Polypropylene | Nonabsorbable monofilament barbed | N/A | Negligible | N/A | N/A | N/A | Uni‐ or bidirectional spiral barb configuration. Similar characteristics otherwise with conventional polypropylene | ||

| Hexafluoropropylene VDF | Pronova | Nonabsorbable monofilament | N/A | Negligible | N/A | Good to very good | N/A | Good alternative to polypropylene; better handling and strength | |

| Stainless Steel | Surgical Stainless Steel (mono); Steel | Nonabsorbable monofilament | N/A | Negligible | N/A | Excellent | N/A | Difficult to handle; may tend to cut through soft tissues | |

| Surgical Stainless Steel (Multi); Flexon | Nonabsorbable multifilament | N/A | Negligible | N/A | Excellent | N/A | Multifilament improves handling; excellent knot security | ||

| Silk | Permahand; Sofsilk | Nonabsorbable multifilament | Proteolytic enzymes | Moderate to severe | 70% after 14 d; 50% after 30 d | Fair | Gradual encapsulation by fibrous tissue | Considered one of the best handling sutures available | |

| Polyester | Mersilene (uncoated); Ethibond Excel (coated); Ticron; Surgidac | Nonabsorbable multifilament | N/A | Mild to moderate | N/A | Fair | Gradual encapsulation by fibrous tissue | Strong, relatively good handling; knot security is a concern |

NA = Not Applicable.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

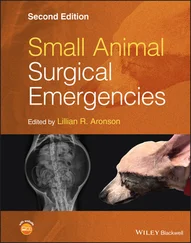

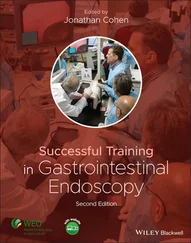

Похожие книги на «Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gastrointestinal Surgical Techniques in Small Animals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.