Maximising the number of replicates or survey points to increase a study's power is desirable. However, this is often constrained by fieldworker, equipment, species, or habitat factors. For example, a common misconception is that behavioural studies in the wild, particularly with large mammals, will yield sufficient data for robust analysis. However, often such data are of poor quality or lacking entirely, ironically because large animals are often hard to observe. Under such circumstances, the observer may have to either abandon the study or report using descriptive or qualitative methods. We cannot emphasis enough the importance of estimating how much time it can take on average to get one data point in order to derive the time needed to complete the whole field study component in sufficient detail for statistical analysis.

Many techniques are not directly comparable with each other, and even using the same technique, but under different conditions (e.g. between habitats with very different vegetation layers, between night time and daylight collections, at different times of the year) may not produce comparable data.

Limitations of the equipment being used may mean that monitoring environmental variables is restricted if, for example, differences between areas are smaller than the accuracy of the equipment allows.

Resource issues may determine the methods available for use: the cost of equipment, necessity for training, ease of relocation of apparatus between sites, and health and safety issues could all limit the choice of methods.

In order to design an appropriate experiment or a survey, you need to think about the type of data you wish to collect. The pieces of information that are recorded (e.g. height of tree, number of birds, density of plants per unit area) are termed ‘variables’, and may be in the form of one of three types of data. The simplest type is categorical or nominal data where each value is identified as one of several distinct categories (e.g. male or female animals; purple, red, or yellow flowers; grasses, ferns, herbaceous plants, shrubs, or trees). Where we can place the categories in some kind of logical order, so that the data are able to be ranked, this is called ordinal data (e.g. large, medium sized, or small ponds; above the high tide line, mid shore, and below the low tide line on a rocky shore). The most detailed type of data are those measurements that not only can be placed in a logical order, but where there is also a known interval between adjacent items in the sequence (e.g. the number of deer in a herd; the temperature in the centre of patches of plants; the depths of a series of ponds). There are two types of measurement data: interval data and ratio data (see Box 1.5). In most cases, the analysis of interval and ratio data uses the same statistical techniques and so in this text we will tend to combine them and refer to them as interval/ratio data or measurement data.

Box 1.5 Differences between interval and ratio data

Interval data have no true zero so that negative values are possible (as in temperature measured on the Celsius scale where 0 °C refers to the freezing point of water rather than the lowest possible temperature) and where measurements cannot be multiplied or divided to give meaningful answers (as in dates).

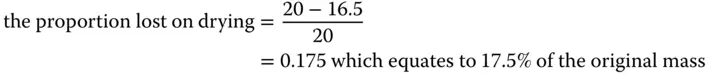

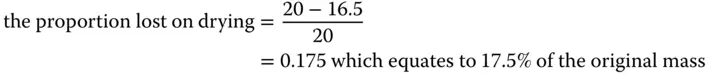

Ratio data are measurements that have an absolute zero point that is the lowest possible value (as in temperature measured on the Kelvin scale where zero Kelvin is absolute zero) and so negative values are not possible (e.g. you cannot have − 6 foxes). With ratio data, all basic mathematical operations can be performed to give meaningful answers. For example, you can derive a ratio of water lost from soil following drying out as follows (where the original mass = 20 g, and dried mass = 16.5 g):

Note that we can readily reduce measurement data to ordinal or categorical, but not the other way around. Thus, if we count the numbers of invertebrates of different species on a particular type of plant, we could subsequently express this in order of dominance from abundant through to rare (an ordinal scale), or indicate the presence or absence of different species (categories). However, if we merely record presence and absence of species, we cannot subsequently calculate the numbers of individuals. Thus, if in doubt, it is safest to collect the information at the highest resolution possible.

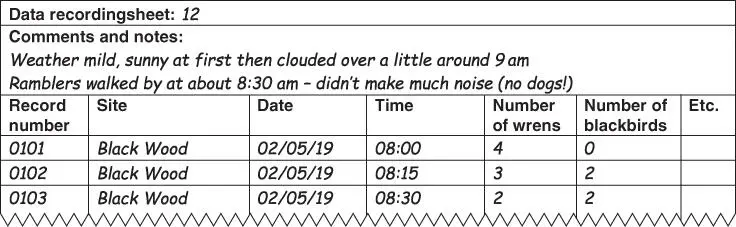

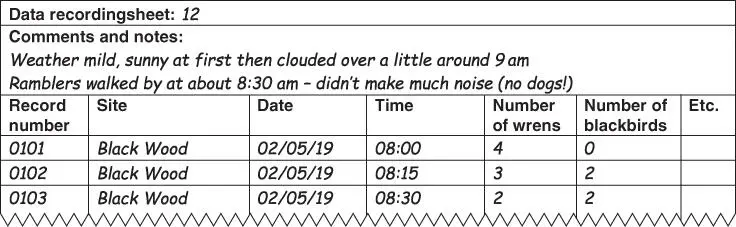

Figure 1.3 Example of a section of a data recording sheet for an investigation into the distribution of woodland birds.

It is good practice to use a standardised data recording sheet (ideally in your field notebook) that is as similar as possible to the way in which data will be entered into a computer for analysis to avoid data transcription errors in moving from paper to a computer spreadsheet. In our example ( Figure 1.3), we have two types of variables: fixed and measured. It is easier to deal with these in order so that fixed variables come first, followed by measured variables. Fixed variables are those determined by the research design and do not vary during the investigation (record number, site, date, and time). Hence, these can be added to the recording sheet early in its production. Measured variables, on the other hand, are those factors recorded during the investigation the values of which will vary depending on the site, date, time, etc. (numbers of wrens, blackbirds, etc.). Sometimes, derived variables are also required (i.e. variables produced from measured data, e.g. the proportions that each species forms of the whole catch). Such derived variables can be added to the right of the measured data once the latter have been entered on a computer spreadsheet, since the required computations are usually easily carried out using spreadsheet functions. In most cases, data will be recorded as numerical values. Where categories (e.g. site) occur, codes or names can be used, although some computer programs will not accept letter codes, so you may need to allocate numeric codes to such variables. You should make sure that any paper copies of results sheets are photocopied or scanned as soon as possible after completion, and that electronic copies are properly backed up.

When implementing a project, it is rarely possible to collect information on all the animals or plants present. Usually we need to use a sample that we hope to be representative of the situation as a whole. The total number of data points that could theoretically be gathered is known as the population (this is a statistical population rather than the actual population of animals or plants – see Box 1.6); the actual number of data points is termed the sample size. Larger samples are usually more representative of populations, although this depends on the variability of the system being studied (small samples may be reliable representations of populations with low variability). Those elements of a system that are calculated (e.g. the mean number of plants, such as plantains, per square metre in a meadow) are termed statistics and are estimates of the true attributes of a statistical population (called parameters – see Box 1.6). So, if we counted all the plantains in the entire meadow, we would be able to calculate the actual mean value per square metre (a parameter). Since it is usually impractical to count all individual plantains, in reality we usually count plantains in a subset of the meadow (i.e. take a sample), and calculate the mean numbers per square metre using this sample in the expectation that it will be representative of the whole site (a statistic). This sort of situation occurs in many types of survey. For example, market researchers obtain opinions from large groups (samples) of people and use these to indicate the attitudes of the population as a whole.

Читать дальше