Before starting work each day, write down the date, weather, general location, nature of the habitat, and purpose of the day's work. Write down any changes in weather or habitat that occur during the day, e.g. ‘At 15.00 hours snow began to fall and visibility was reduced to 20 m’. When observing behaviour, note the sampling method, how animals were chosen for observation, and the recording method (e.g. whether you noted all occurrences or used a time‐sampled method). If animals or start times are chosen at random, note how this was done.

Note the type and model number of any equipment (e.g. GPS receiver type Garmin 12). Some instruments need calibrating at intervals, so record the time of calibration and any raw data and subsequent calculations so that any arithmetic errors can be identified and corrected later. Use your notebook to create rough species accumulation curves, etc. so you can tell when you should stop collecting data (see p. 31). Although notes should be made at the time observations are made, it can be difficult to observe and write at the same time, but if you do rely on memory, you should note this. Write exactly what you see or hear, e.g. when describing behaviour do not ascribe a function to it in the guise of a description (i.e. do not write that a goose was ‘vigilant’ when you mean that the bird was in a standing posture with an elongated neck and raised head).

Sketches enhance any photographs you take of your study sites and you will have a sketch available in your notebook the next time you visit the area. Sketches can be added to subsequently (annotating any changes with the date of the amendment). The value of sketches can be increased by explanatory labels. A careful sketch can aid species identification and will help to jog your memory when you encounter a species in the future; such sketches are more valuable if labelled with the diagnostic feature(s) you use (e.g. ‘two spots on forewing’ or ‘sepals bent backwards’). Landscapes change over time and maps may not reflect this. In some cases, no map of a suitable scale may be available, and a sketch map can be made using compass and tape, or by pacing out distances using a pedometer. This may be adequate to note the locations of those animals or plants of interest.

It is also useful to record any notes and actions from supervisory or team meetings, both as a reminder and to ensure that any designated actions have been completed as planned.

Although you might worry that using a pilot study will delay the start of you collecting the data you need for your project, in reality it may save you time and further problems down the line. Trying out your project over a small scale (including in time), will enable you to better plan the logistics of implementing your project. Not only do you get a chance to ensure you can realistically complete the project, you will also gain an insight into the variability and values of data you are collecting. Such insights are particularly useful when assessing the sample size required (p. 30). Pilot studies enable you to become familiar with your techniques so that the data collected will be the result of skilled implementation, rather than early data being the result of less well managed techniques that are new to you. Any changes that you include to your final design as a result of the experiences from your pilot studies should be documented in your final methods section of your report.

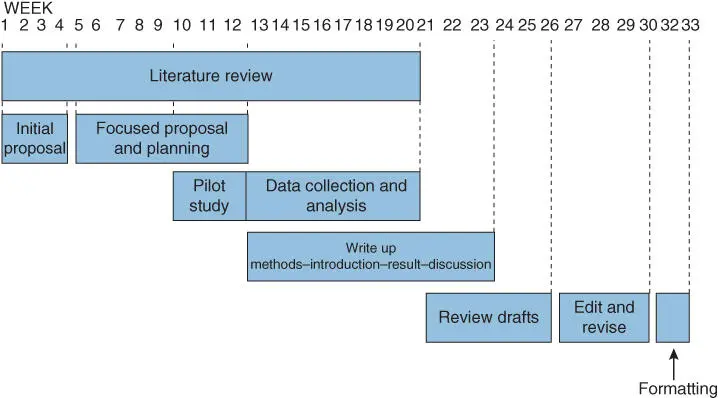

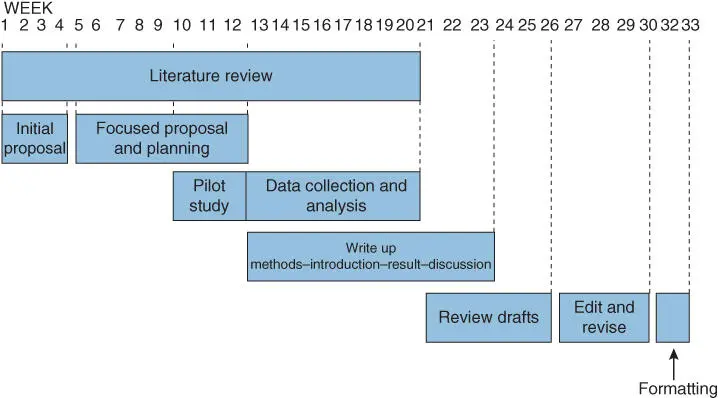

Figure 1.2 Example timescales for a medium‐term research project. Note that health and safety, ethical, and legal issues should be examined within the initial proposal and a refined risk assessment produced during the focussed proposal and planning phase. This risk assessment should be revisited regularly throughout the project.

Conducting a piece of research within a relatively short timespan is a demanding process and will require careful time management. You will need to allow time to check the feasibility of the research project and should also add sufficient time for method training or familiarisation. Ensure that you leave time spare to allow for the almost inevitable problems associated with both fieldwork and laboratory analysis. Check out your methods by first running a pilot to help identify any pitfalls and inadequacies. It is easy to underestimate how long it takes to analyse, interpret, and write up a research report. Figure 1.2illustrates a timetable in the form of a Gantt chart for a research project expected to last 33 weeks – around a full academic year: many research projects are substantially shorter than this. Note how the time allocated to actually collecting the data is relatively short and overlaps with the ongoing literature review and writing process. Also, you are strongly urged to begin writing the report before completing your data collection; it should be possible at this stage for you to write the methods and introduction since the former will describe what you have been doing, whilst the latter reflects your background reading of the literature. Table 1.1shows an example timescale for a research project lasting a week (e.g. on a field course). Note that even with such a short timescale, sufficient time needs to be devoted to planning the project to ensure the best chance of success (see Box 1.4).

Table 1.1Example timescales for a short research project.

| Day |

Morning |

Afternoon |

Evening |

| 1 |

Select topic, identify aims and hypotheses, create programme of study, select sites and techniques, identify major resources required, complete risk and ethical assessments |

Test, and become experienced in using, techniques and equipment, implement a pilot study |

Evaluate pilot study, amend programme of study |

| 2 |

Implement amended programme and collect data |

Enter data into spreadsheet, write methods |

| 3 |

Collect data |

Enter data into spreadsheet, write introduction |

| 4 |

Collect data |

Enter data into spreadsheet, edit introduction and methods |

| 5 |

Collect data |

Enter data into spreadsheet, plan results tables and figures |

| 6 |

Collect data |

Analyse data |

| 7 |

Write results section |

Write discussion |

Complete report |

Box 1.4 Some tips on time management

Be realistic about what you can achieve in the time you have available and work within your strengths and weaknesses.

Plan your long‐term goals.

Have a weekly plan, with realistic and achievable targets, and update this on a regular basis to reflect your progress.

Identify not only the key phases of your research project, but also other areas that will take up your time (both in terms of study and general living) to ensure that your research timescales are realistic and that your aims are achievable.

Prioritise your work into that you have got to do, that you ought to do, and that you would like to do but may not have time.

Make good use of your time: a trip by train may be an ideal opportunity to read references or edit your manuscript.

Statistical considerations in project design

Since research is about asking questions, you need to design your project so that it will answer them effectively, without allowing your design to introduce ambiguous results, or results that are open to other interpretations. This is where the planning phase starts to define what you are going to measure and how. If, for example, we investigate the types of birds found inhabiting a woodland patch, then we have a choice of ways in which we record the data. We might note how many individual birds there are, or the numbers of each feeding type (insect feeders, seed feeders, etc.), or how many individuals there are in each species. These measurements enable us to obtain a picture of the birds found in a woodland patch. If we monitor birds only in a single woodland patch, we could worry that our chosen woodland is unusual in some way and therefore not representative of woodland patches in general. We could therefore examine a series of patches and obtain data for 10 or more of these. Now, if we wish to describe how many birds were found in all of these woodlands, we require some sort of descriptive statistic to summarise the information across 10 or more patches. Descriptive techniques include estimates of the average values per sampling unit (e.g. per site), population estimates and densities, methods of describing distributions (i.e. whether organisms are distributed randomly, evenly or in aggregations), and measures of community richness including diversity and evenness indices. These techniques are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.

Читать дальше