BOX 2.2

Molecular Phylogeny

The translation apparatus is the most highly conserved of all the cellular components. The structures of ribosomes, translation factors, aaRS enzymes, tRNAs, and the genetic code itself have changed remarkably little in billions of years of evolution. This is why these components have been used extensively in molecular phylogeny. By comparing the sequences of the rRNAs and other components of the translation apparatus and determining how much they have diverged, it has been possible to establish phylogenetic trees that include all organisms on Earth. The high level of conservation probably also explains why so many different antibiotics target the translation apparatus compared to other cellular components. An antibiotic designed to inhibit translation in one type of bacteria will probably inhibit translation in many other types of bacteria.

The conservation of components of the translation apparatus is so high that “rooted” evolutionary trees can be made that include eukaryotes and archaea (see the introduction). Such trees are usually not too different from what has been obtained from physiological and other comparisons, but there are sometimes surprises. Also, the sequence of the translation elongation factors led to the suggestion that the archaea are more closely related to eukaryotes than they are to other bacteria, prompting the change of their name to archaea from the original designation “archaebacteria.”

Many of the initiation and elongation factors in bacteria have counterparts in archaea and eukaryotes. Nevertheless, the major differences in the translation apparatus come in the translation initiation factors. While bacteria have only three initiation factors (some of them have more than one form), archaea and eukaryotes have many more. As is the case with other cellular functions, archaea share more of their initiation factors with eukaryotes than they do with bacteria. Also, some of the initiation factors, while conserved, seem to have somewhat different functions in the three kingdoms of life. These differences may reflect differences in the initiation sites for translation.

Ganoza MC, Kiel MC, Aoki H.2002. Evolutionary conservation of reactions in translation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66:460–485.

Hug LA, Baker BJ, Anantharaman K, Brown CT, Probst AJ, Castelle CJ, Butterfield CN, Hernsdorf AW, Amano Y, Ise K, Suzuki Y, Dudek N, Relman DA, Finstad KM, Amundson R, Thomas BC, Banfield JF.2016. A new view of the tree of life. Nat Microbiol 1:16048.

Iwabe N, Kuma K, Hasegawa M, Osawa S, Miyata T.1989. Evolutionary relationship of archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes inferred from phylogenetic trees of duplicated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:935 5 –9359.

Owen RJ.2004. Bacterial taxonomics: finding the wood through the phylogenetic trees. Methods Mol Biol 266:353–383.

Pace NR.2009. Mapping the tree of life: progress and prospects. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73:56 5 –576.

Woese CR.1987. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev 51:221–271.

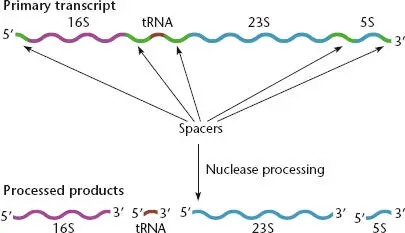

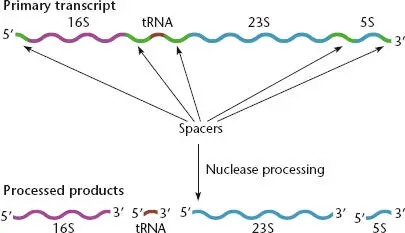

Figure 2.16 Precursor of rRNA. The precursor transcript (top) contains the 16S, 23S, and 5S rRNAs, as well as one or more tRNAs. RNases cut the individual rRNAs and tRNAs out of the precursor after it is synthesized.

The faster a cell grows, the more protein it needs to make. Ribosomes are the site of protein synthesis; therefore, cells can increase their growth rate only if they increase the number of ribosomes. In most bacteria, the coding sequences for the rRNAs are repeated in several copies in the genome. Duplication of these genes leads to higher rates of rRNA synthesis in these bacteria. Although the precursor RNAs encoded by these different copies produce identical rRNAs, the rRNA gene clusters often contain different tRNAs and spacer regions.

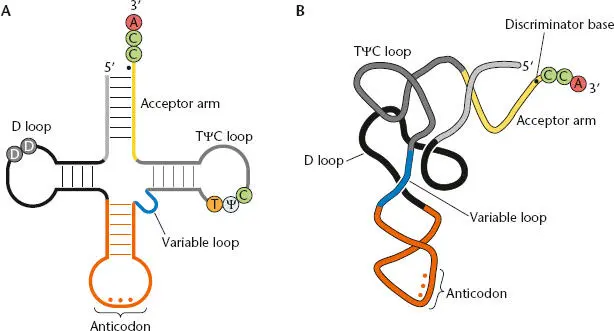

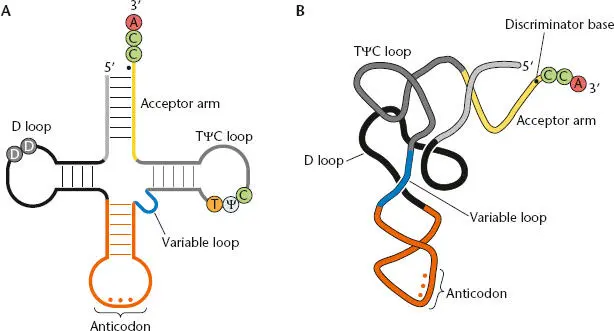

Some of the RNAs in cells are modified after they are made. For example, specific nucleotides in the rRNAs are methylated. The tRNAs are probably the most highly processed and modified RNAs in cells (see Björk and Hagervall, Suggested Reading). Figure 2.17shows a “mature” tRNA that was originally cut out of a much longer molecule that may also have included the rRNAs as well as other tRNAs. Some of the bases within the tRNA are modified by specific enzymes that produce altered bases, such as pseudouracil and dihydrouracil. A CCA sequence is found on the 3′ end of all tRNAs. In some cases this is encoded in the gene, and therefore is part of the precursor RNA, while in others it is added posttranscriptionally by an enzyme called CCA nucleotidyltransferase.

Figure 2.17 Structure of mature tRNAs. (A)Standard clover leaf representation of tRNA, showing the base pairing that holds the molecule together and some of the standard modifications. D is the modified base dihydrouridine. tRNAs also contain thymine (T) and pseudouracil (Ψ) among other modifications. The amino acid is attached to the terminal A of the CCA at the 3′ end. (B)Folding of tRNA into its tertiary structure. The discriminator base (black dot), immediately upstream of the CCA, is important for tRNA recognition by the correct aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS).

Different classes of RNAs have very different survival times in the cell. Highly structured RNAs, like rRNAs and tRNAs, are very stable and may persist through several rounds of cell division. Individual rRNAs are stabilized when they are assembled into ribosomal particles (see below), while tRNAs are stabilized because they are generally present in a complex with their cognate aaRS or with translation elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu)(see below). In contrast, most bacterial mRNAs are very unstable, with an average half-lifein E. coli of 1 to 3 minutes; this term refers to the time required for the amount of an RNA to decrease to 50% of its initial level. The short half-life of mRNAs in bacteria contrasts with the situation in eukaryotes, where mRNAs are often very stable (with a half-life of hours). Efficient mRNA degradation is important for gene regulation and also releases nucleotides for use in new rounds of transcription. A variety of RNases participate in mRNA degradation, and the profiles of RNases vary somewhat in different groups of bacteria.

There are two major classes of RNases (Table 2.1 and Figure 2.18). Endoribonucleasescleave the sugar-phosphate backbone of the RNA within the RNA chain to generate two smaller RNA products, one with a 3′ hydroxyl and the other with a 5′ monophosphate. Exoribonucleasesdigest the RNA processively, removing 1 nucleotide at a time, starting at a free end. Most organisms have multiple endo- and exoribonucleases, and some subtypes of these enzymes are found in many different organisms, while others are present in only certain groups of organisms. In E. coli , all exoribonucleases that have been identified bind to the 3′ end of an RNA substrate and digest the RNA in a 3′-to-5′ direction. In contrast, Bacillus subtilis and a number of other organisms contain both 3′-5′ exoribonucleases and 5′-3′ exoribonucleases. At least one of the B. subtilis 5 ′-3′ RNases (RNase J2) has both exoribonucleolytic and endoribonucleolytic activities (Table 2.1).

Читать дальше