Jane Flint - Principles of Virology

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jane Flint - Principles of Virology» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Principles of Virology

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Principles of Virology: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Principles of Virology»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Volume I: Molecular Biology

Volume II: Pathogenesis and Control

Principles of Virology, Fifth Edition

Principles of Virology — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Principles of Virology», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

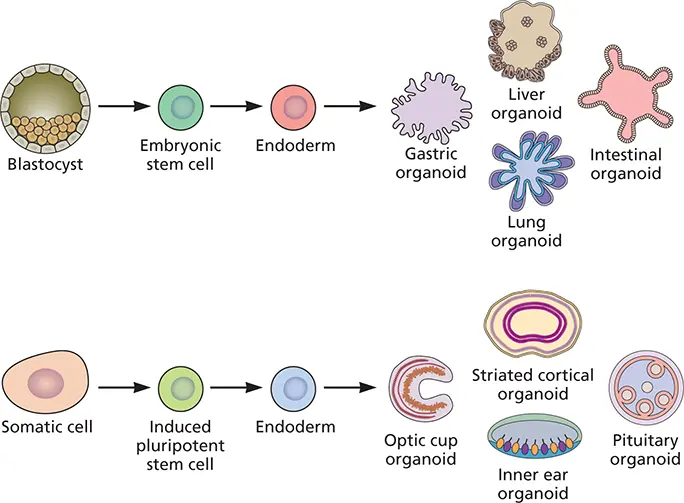

Another type of three-dimensional cell system is the multicellular, self-organizing organoidthat approximates the organization, function, and genetics of specific organs. Organoids are derived from either pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs or embryonic stem cells) or adult stem cells from different organs. Organoids that model many organs such as intestine, stomach, esophagus, and brain have been established, and many have been validated for the study of a variety of viral infections ( Fig. 2.3). For example, for years propagation of human noro-viruses eluded virologists until the development of intestinal organoids.

The differentiation of stem cells into organoids depends on growth conditions and nutrients. For example, one type of brain organoid can be established from human pluripotent stem cells by embedding the cells in a gelatinous protein mixture that resembles the extracellular environment of many tissues. In the absence of further cues, the stem cells differentiate into structures typical of many diverse brain regions, including the cortex. In contrast, the production of intestinal organoids requires agonists of a particular signal transduction pathway. Current attempts to improve organoid cultures include the addition of immune cells, vasculature, and commensal microorganisms, to more accurately reflect the details of tissue and organ architectures.

Figure 2.3 Production of organoids from stem cells. The different germ layers shown (endoderm and ectoderm) may be derived from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in vitro with specific differentiation protocols. After transfer into 3-dimensional systems these cells produce organoids that recapitulate the developmental steps characteristic of various organs.

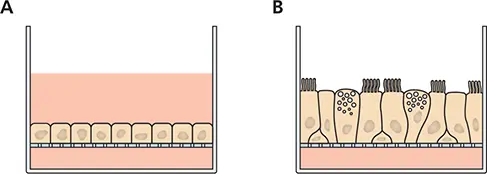

Air-liquid interface culturesare used to model the respiratory tract, a major site of virus entry and infection. This organ presents a challenge because its structure differs from the pharynx to the alveoli. In the trachea and bronchi, the epithelium comprises a single layer of columnar cells which contact the basement membrane. In the alveoli the epithelium is made of a thin, single cell layer to facilitate air exchange. Air-liquid interface cultures may be produced from primary human bronchial cells or respiratory cell lines ( Fig. 2.4).

Because viruses are obligatory intracellular parasites, they cannot reproduce outside a living cell. An exception comes from the demonstration in 1991 that infectious poliovirus could be produced in an extract of human cells incubated with viral RNA, a feat that has not been achieved for any other virus. Consequently, most analyses of viral replication have used cultured cells, embryonated eggs, or laboratory animals. For a discussion of whether to call these different systems in vivo or in vitro , see Box 2.4.

Evidence of Viral Reproduction in Cultured Cells

Before quantitative methods for measuring viruses were developed, evidence of viral propagation was obtained by visual inspection of infected cells. Some viruses kill the cells in which they reproduce, and they may eventually detach from the cell culture plate. As more cells are infected, the changes become visible and are called cytopathic effects.

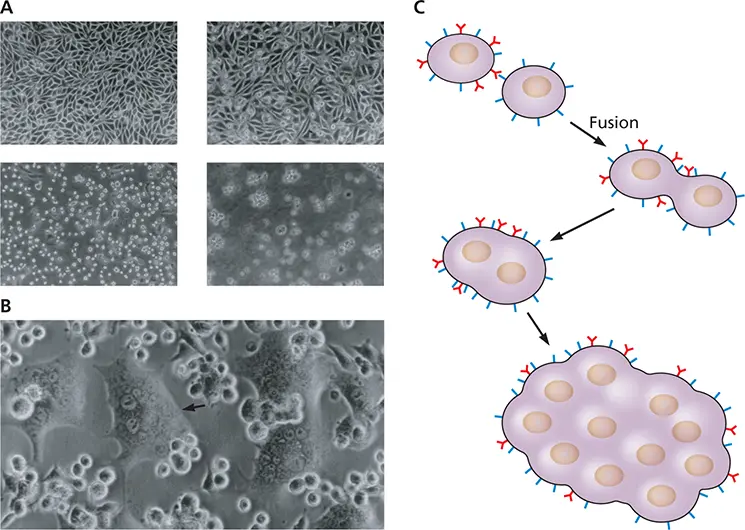

Many types of cytopathic effect can be seen with a simple light or phase-contrast microscope at low power, without fixing or staining the cells. These changes include the rounding up and detachment of cells from the culture dish, cell lysis, swelling of nuclei, and sometimes the formation of a group of fused cells called a syncytium( Fig. 2.5). High-power microscopy is required for the observation of other cytopathic effects, such as the development of intracellular masses of virus particles or unassembled viral components in the nucleus and/or cytoplasm (inclusion bodies), formation of crystalline arrays of viral proteins, membrane blebbing, duplication of membranes, and fragmentation of organelles.

Figure 2.4 Production of airway-liquid interface cultures of bronchial epithelium. (A)Epithelial cells are seeded onto a permeable membrane and cell culture medium is supplied on both apical (top) and basal (bottom) sides. (B)When the cells are confluent, medium on the apical side is removed. Contact of the cells with air drives differentiation of cells towards types found in the airways, such as goblet cells, ciliated and nonciliated cells, and basal cells. Cultures may be produced that mimic tracheobronchial cells, with different cell types, or human alveolar cells with only two cell types (not shown).

BOX 2.4

TERMINOLOGY

In vitro and in vivo

The terms “in vitro” and “ in vivo” are common in the virology literature. In vitro means “in glass” and refers to experiments carried out in an artificial environment, such as a glass or plastic test tube. Unfortunately, the phrase “experiments performed in vitro ” is used to designate not only work done in the cell-free environment of a test tube but also work done within cultured cells. The use of the phrase in vitro to describe living cultured cells leads to confusion and is inappropriate. In vivo means “in a living organism” but may be used to refer to either cells or animals. Those who work on plants avoid this confusion by using the term “in planta.”

In this textbook, we use in vitro to designate experiments carried out in the absence of cells, e.g., in vitro translation. Work done in cells in culture is done ex vivo , while research done in animals is carried out in vivo .

The time required for the development of cytopathology varies considerably among animal viruses. For example, depending on the size of the inoculum, enteroviruses and herpes simplex virus can cause cytopathic effects in 1 to 2 days and destroy the cell monolayer in 3. In contrast, cytomegalovirus, rubella virus, and some adenoviruses may not produce such effects for several weeks.

Figure 2.5 Development of cytopathic effect. (A)Cell rounding and lysis during poliovirus infection. Shown are uninfected cells (upper left) and cells 5.5 h after infection (upper right), 8 h after infection (lower left), and 24 h after infection (lower right). (B)Syncytium formation induced by murine leukemia virus. The field shows a mixture of individual refractile small cells and flattened syncytia (arrow), which are large, multinucleated cells. Courtesy of R. Compans, Emory University School of Medicine. (C)Schematic illustration of syncytium formation. Viral glycoproteins on the surface of an infected cell bind receptors on a neighboring cell, causing fusion.

The development of characteristic cytopathic effects in infected cell cultures is frequently monitored in diagnostic virology after isolation of viruses from specimens obtained from infected patients or animals. In the research laboratory, observation of cytopathic effect can be used to monitor the progress of an infection, and is often one of the phenotypic traits that characterize mutant viruses.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Principles of Virology»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Principles of Virology» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Principles of Virology» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.