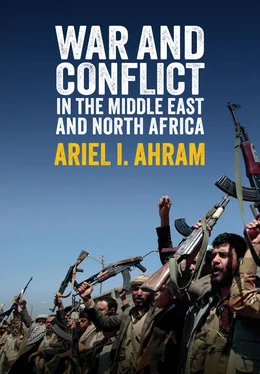

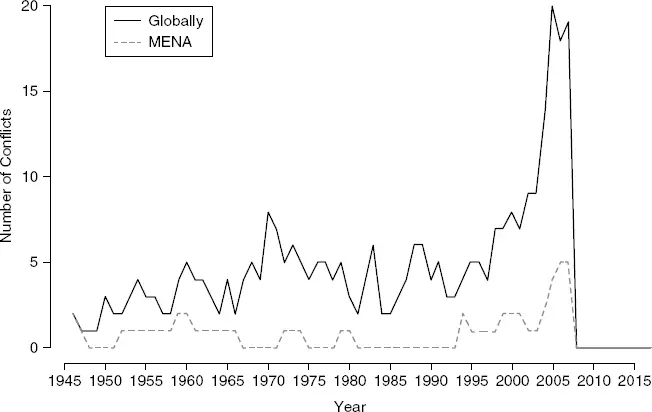

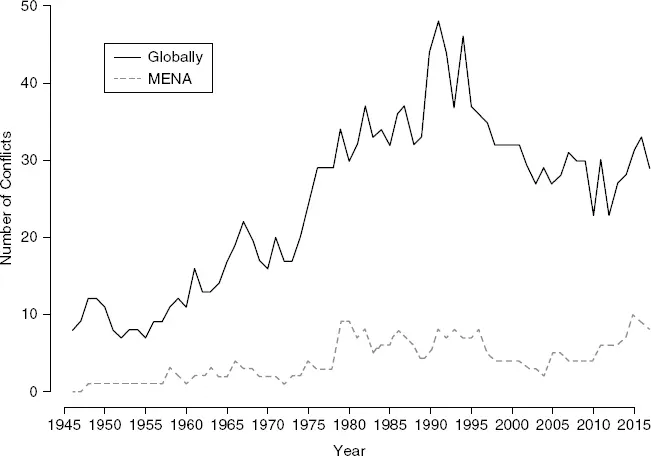

Figure 1.3 Years at war for MENA countries, 1945–2017

Source: Peace Research Institute, Oslo/Uppsala Conflict Data Project, data available at https://www.prio.org/Data/Armed-Conflict/UCDP-PRIO/ ; Gleditsch et al., “Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset.”

Second Cut: Conflict Types

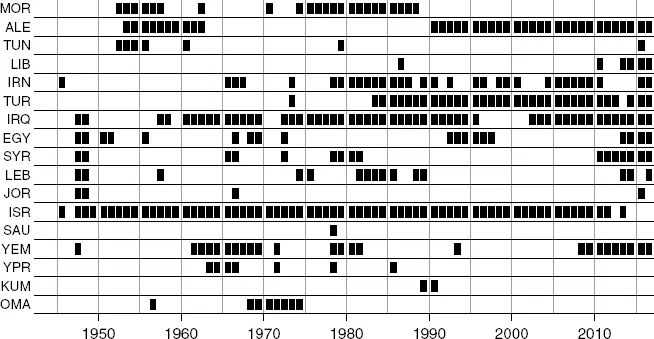

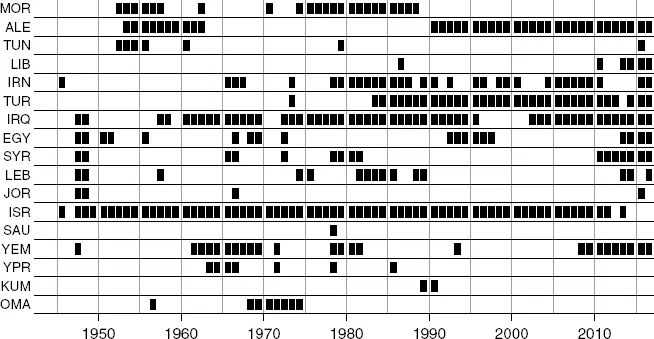

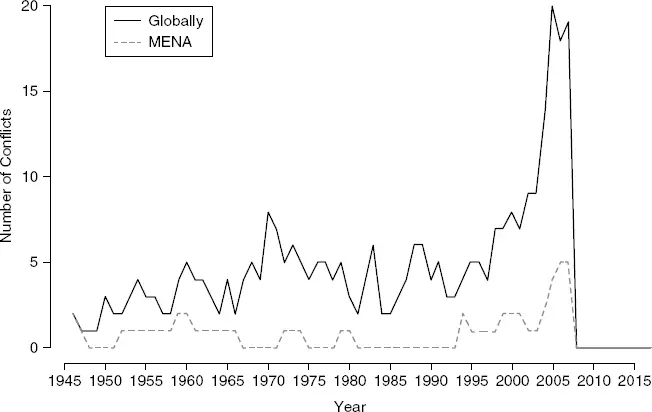

Another step in interrogating claims of regional exceptionalism is to examine the types of war fought within MENA. Figure 1.4 presents the data on inter-state war regionally and globally. Interstate war is clearly the least common form of warfare globally. Inter-state war is nearly entirely absent from Latin America and Europe. Some analysts deem interstate war so rare as to be obsolete or extinct. 15Yet MENA consistently accounts for a significant portion of interstate conflicts globally. Much of this comes from the persistence of conflicts between Israel and its neighbors, a topic to which we shall return later on. But there are other cases to consider as well, such as the Iran–Iraq War and the Iraqi war against Kuwait in 1990 and 1991. The fact that MENA seems to be uniquely prone to interstate conflict adds an important caveat to the global-level analysis favored by both CoW and PRIO/UCDP projects. It suggests that regional security complexes, not just world systems, have a significant part in shaping conflict.

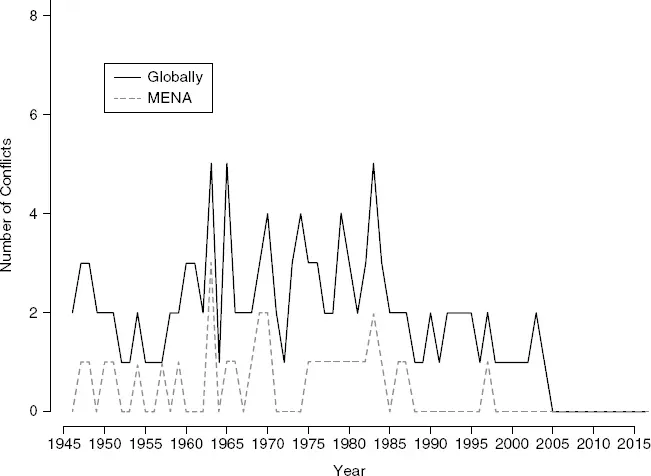

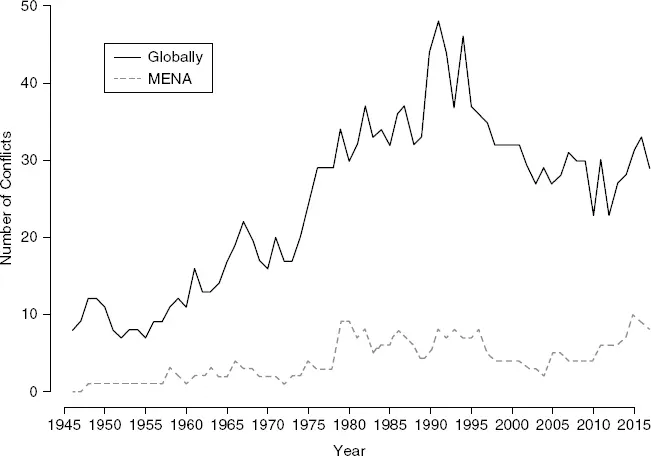

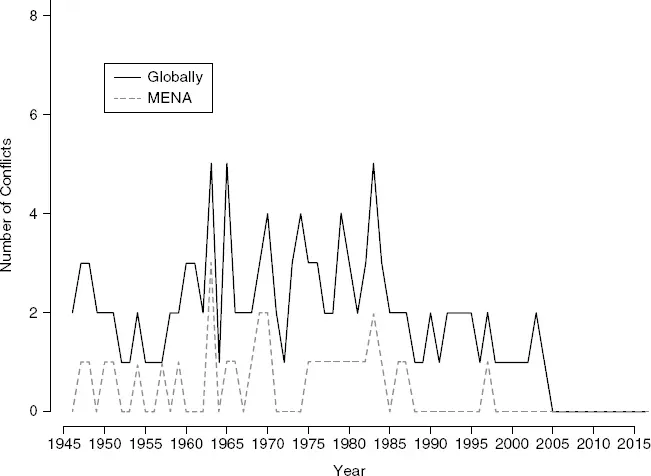

Figures 1.5 and 1.6 present the data on internal (civil) wars and internationalized internal wars. In examining trends in internal war, MENA is much less remarkable.

Figure 1.4 Interstate conflicts, MENA v. the world

Source: Peace Research Institute, Oslo/Uppsala Conflict Data Project, data available at https://www.prio.org/Data/Armed-Conflict/UCDP-PRIO/ ; Gleditsch et al., “Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset.”

The global trend in internal wars began increasing in the 1960s and peaked in the mid-1990s, with MENA’s trajectory basically following this global course. Internationalized internal wars rose dramatically in the mid-1990s globally, with MENA following course through the 2000s and 2010s.

Third Cut: Conflict Magnitude

Beside the frequency and form of war is the question of war’s magnitude. Here, again, social scientists have run into substantial issues related to conceptualization and data collection. It requires a definition of war – which is difficult enough. It also requires an idea of the mechanisms by which war causes destruction. The human security approach, as discussed above, insists on accounting for not just the damage inflicted by and upon armies, but also the suffering borne by civilians. Indeed, it points out that over the twentieth century, civilians, not soldiers, experienced by far the most deaths during war. 16Statisticians of war use the term battle deaths to denote all deaths, whether of civilians or combatants, attributable to direct military action. Battle deaths therefore include deliberate attacks as well as inadvertent (i.e., collateral) damage.

Figure 1.5 Internal wars, MENA v. the world

Source: Peace Research Institute, Oslo/Uppsala Conflict Data Project, data available at https://www.prio.org/Data/Armed-Conflict/UCDP-PRIO/ ; Gleditsch et al., “Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset.”

While the idea of battle deaths is somewhat intuitive, collecting accurate data is practically very difficult. Armies often keep track of their own casualties and try to monitor the strengthening or weakening of their adversaries. However, these data are often classified, censored, or subject to political bias. There is a tendency to undercount or ignore civilian deaths, either by denying they occur at all or by reclassifying the dead as combatants. This legitimates them as targets for violence. Reflecting on the experience of the Syrian civil war, novelist Khaled Khalifa observed that “during war, a body loses all meaning.” 17

But there is a countermove against this as well. International organizations have sought to collate reports of deaths from among combatant countries. A growing network of civil society organizations have developed techniques to cull data through local media reports about violent incidents. They have also begun using techniques for “crowdsourcing” casualties through social media. 18This approach, though, has its limitations. As highlighted by Megan

Figure 1.6 Internationalized civil wars, MENA v. the world

Source: Peace Research Institute, Oslo/Uppsala Conflict Data Project, data available at https://www.prio.org/Data/Armed-Conflict/UCDP-PRIO/ ; Gleditsch et al., “Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset.”

Price, Anita Gohdes, and Patrick Ball of the Human Rights Data Analysis group, “the chaos and fear that surround conflict mean that killings often go unreported and consequently remain hidden from view.” 19Reliable data become the scarcest in the areas most afflicted by violence. Moreover, because these techniques rely on third-party reporting via media or crowdsourcing, they tend to highlight violence in more densely populated urban settings while undercounting violence committed in remote rural areas. 20While there are more data than ever on battle deaths, these data are often disparate and contradictory.

The Iraq War was a case in point. The United States refused to release data on civilian deaths in Iraq, and it is unclear whether it even collected such information. American and British military officials declared that they “don’t do body counts.” 21President George W. Bush stated that “30,000 [Iraqi civilians], more or less, have died as a result of the initial incursion and the ongoing violence.” Aides later clarified that this was not an official statistic, but an estimate based on published news accounts. Other organizations offered substantially different figures. In August 2006, the NGO Iraqi Body Count (IBC) estimated that number at between 47,016 and 52,142. The Brookings Institution, a US think tank, estimated the number at 62,000. 22

But wars do not kill just by guns and bombs. They also damage the institutions necessary to assure access to basic needs like food, healthcare, and sanitation. They level economies and impel displaced populations and refugees. 23During World War I, for example, combat largely spared Lebanon and Syria. Nevertheless, Ottoman military and labor conscription and their requisitioning of crops, timber, and fuels led to severe shortages for the civilians in the area and left millions vulnerable to hunger. Historians estimate that between 100,000 and 200,000 may have succumbed to starvation or disease and tens of thousands were displaced. 24

The Yemeni civil war of the 2010s offers a more recent example. Blockades and direct strikes on food distribution centers, sanitation facilities, and hospitals have contributed to mass hunger and precipitous declines in public health, including a massive cholera outbreak. 25UN officials called this “the worst humanitarian crisis of our time.” An estimated three-quarters of the Yemeni population require food assistance and 1.8 million children suffer from acute malnourishment. 26

Читать дальше