In its most basic sense, then, the term “MENA” reflects an imperial outlook that the people of the region do not share. Those living in Rabat, Cairo, or Tehran do not naturally think of themselves as “east” of anything; their politics and their territories deserve center stage. Although today the terms “Middle East” and its adjuncts are common in regional discourse, other conceptual terminology is available. 12Indigenous terms like “Arab world” ( al-‘alam al-‘arabi ) or “Domain of Islam” ( dar al-Islam ) suggest different ideas about the origins of regional unity and shared regional destiny. Historian Nikki Keddie pointed out that the idea of “the Muslim world is too unwieldy a unit for most ordinary mortal scholars to deal with.” 13Nonetheless, she stressed, it must be remembered that this is the unit with which many inhabitants of the Middle East historically self-identified. Invocations of Islamic unity continue to the present day. On the other hand, when politicians or pundits in the region describe their country as “Western,” they are often asserting their superiority over otherwise “eastern” neighbors. Regional terminology comes laden with particular historical and normative connotations. 14

For the purposes of this book, MENA stretches roughly from the Atlantic coast and the Atlas mountains eastward across the southern edge of the Mediterranean to the Levant, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Persian Gulf littoral region. It includes the following countries: Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Yemen. This agglomeration of countries more or less mirrors the administrative arrangement used in the regional directorates of the United Nation and World Bank. Like many regional delineations, this is a plainly imperfect sense of geographic, historical, and cultural proximity and homogeneity. 15

About 436 million people inhabit the twenty MENA countries, comprising a little more than five percent of the world’s population. Most of these people are Arabic-speakers and Sunni Muslim, although with a variety of dialects and forms of religious practices. Iran, one of the most populous MENA countries, by contrast, is overwhelmingly Shi’ite Muslim and Persian-speaking. Israel has a Jewish majority. Although small in population, Israel plays an outsized military and political role in the region. There are sizable Christian minorities in Egypt, Syria, Palestine, Iraq, and especially Lebanon, which have played significant roles in regional politics as well.

The region is also economically diverse. The most populous MENA countries, namely Iran, Egypt, Algeria, Iraq, Syria, and Tunisia, all fit within the broad bracket of the world’s middle-income states. They are, in this sense, not nearly as well off as those of Western Europe or the United States, but significantly richer than some of the poorest regions of the world, like sub-Saharan Africa. In contrast, Qatar, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE have some of the highest per capita wealth in the world. These economies and the political systems that emerged from them are famously dependent on oil and gas revenues. Israel, a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), is rich for another reason: it has an advanced industrial and service economy derived from high tech. At the other end of the spectrum, Yemen is among the world’s poorest countries. According to World Bank estimates, in 2005 nearly 10 percent of Yemenis lived below the international poverty line (roughly $1.90 per day). The situation has gotten much worse through the wars of the 2010s. We shall see later on how these cultural and economic features influence war and conflict in the region.

War occupies a peculiar place in both popular and scholarly discussions of MENA. Certainly, wars are often and repeatedly remarked upon. There are hundreds of texts written about individual wars or enduring conflicts such as the Arab–Israeli wars. There is a burgeoning literature on the more recent civil wars and regional conflicts featuring, among others, the United States, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Turkey, Libya, Yemen, Iraq, Syria, and a host of non-state belligerents. 16Despite this specificity, though, war as a general phenomenon remains an under-explored and under-theorized feature of MENA’s politics. War stands as the elephant in the room in major textbooks on MENA’s international relations. They skirt the burning question of why violent conflict is such a prominent and durable feature in MENA’s regional affairs and how such violence affects the region socially and politically. 17

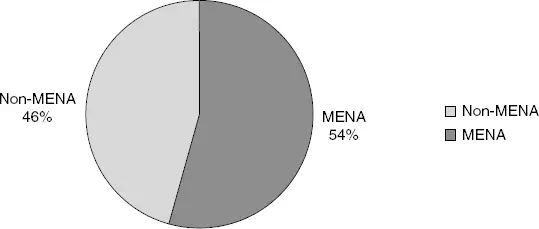

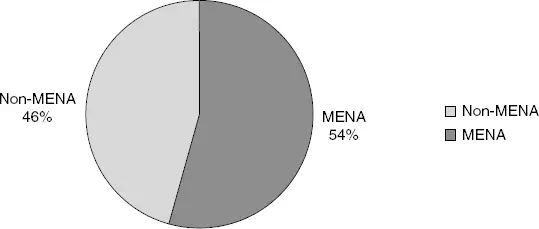

Figure 0.1 MENA’s share of global battle deaths in 2017

Source: Peace Research Institute Oslo/Uppsala Conflict Data Project, data available at https://www.prio.org/Data/Armed-Conflict/UCDP-PRIO/ ; Nils Petter Gleditsch et al., “Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset,” Journal of Peace Research 39, no. 5 (2002): 615–37.

There are a number of reasons why students and scholars should approach the question of conflict and war in MENA. One of the main reasons – and the primary purpose of this book – is analytical. MENA seems to be outside the norm of global peace and stability. We can make this case, albeit anecdotally, by looking at one recent year as an example. According to researchers at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and Uppsala University’s Conflict Data Program (UCDP), premier organizations involved in collecting data on armed conflict, there were forty-nine wars going on around the world in 2017 which claimed a total of about 69,000 lives through battle deaths (battle deaths included both civilians and fighters killed as a result of direct combat). Of these, nine of the wars and 37,500 of the battle deaths occurred in MENA, a region which comprises only one-twentieth of the world’s population, as shown in Figure 0.1. Armed with these figures, it is perhaps natural to presume that MENA suffers a unique pathology, a proclivity to war that spares other, more fortunate, regions.

This book is skeptical about the proposition that there is a unique conflict proneness in MENA, but takes seriously the charge of explaining the factors that seem to make war so frequent in the region. Overall, the book applies the same techniques and approaches to explain conflict in MENA as used in any other part of the world. As discussed later on, a “snapshot” look at cross-national statistics like these can be misleading. Data accuracy is always challenging. Moreover, a focus on battle deaths alone leaves out the impact of war on civilian infrastructure, such as the destruction of hospitals and water treatment facilities, which can lead to further deaths from disease or starvation. 18

A second reason to examine war and conflict in MENA is to consider their effects. These statistics on battle deaths and war frequency also do not account for the “long tail” of conflict, its impact on political and economic development. On one hand, MENA’s wars have brought down governments, ruined economies, fractured families, and killed people. On the other hand, wars have also spurred political and economic innovation, catalyzed social transformation, and fostered new senses of national belonging. 19Addressing both the destructive and productive aspects of war in MENA is critical. The sheer variety and profligacy of violence in MENA can yield important insights into the nature of war, conflict, and political order. Twenty years ago, political scientist Steven Heydemann put forth an ambitious agenda to study the interaction between war and social change in the region:

Читать дальше