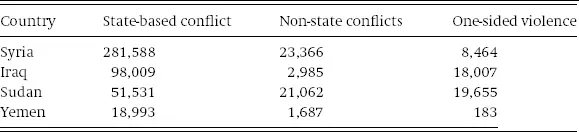

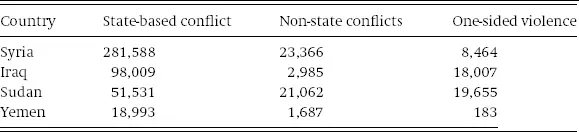

Table 1.2 State, non-state, and one-sided violence in MENA, 1989–2017

Source: Pettersson and Eck, “Organized Violence, 1989–2017.”

Terrorism is closely correlated with asymmetrical internal wars, but it is far from the most consequential form of violence. While much of the United States and other world powers exhibit concern about terrorist attacks emanating from the Middle East, terrorism is hardly a peculiar characteristic of the region.

Internal war and terrorism often stem from states’ inability to control violence effectively. This is not the same, though, as to say that states are somehow exempt from or uninvolved in such violence. In his study of war and conflict in Africa, Paul Williams argues that a state-centric perspective on Africa’s conflicts would be inadequate and inappropriate “because many of the continent’s armed conflicts take place on the peripheries of, or outside, the African society of states and do not involve government soldiers.” 35In MENA, by contrast, the exact opposite prevails. Even when violence is conducted by non-state actors, it is largely oriented toward winning control over states or establishing alternative political structures, that is, new states.

Table 1.3 Ten countries with the most terrorist events in 2018

Source: Global Terrorism Database, available at https://www.start.umd.edu/data-tools/global-terrorism-database-gtd .

| Country |

No. of events (% of global total) |

| Afghanistan |

1,776 (18) |

| Iraq |

1,362 (14) |

| India |

888 (9) |

| Nigeria |

645 (7) |

| Philippines |

601 (6) |

| Somalia |

527 (5) |

| Pakistan |

480 (5) |

| Yemen |

325 (5) |

| Cameroon |

235 (2) |

| Syria |

232 (2) |

Counting armed conflicts, battle deaths, and indirect deaths is frustratingly inexact. The exercise depends on disputed concepts that, in turn, link to deeper normative concerns about what types of violence are legitimate versus illegitimate. Terms like “soldier,” “terrorist,” “civilian,” “victim,” or “casualty” connote different statuses within organizations devoted to fighting. Even if these theoretical and moral issues are resolved, the techniques used to collect data about war themselves face severe practical limitations.

Nevertheless, grappling with these conceptual, normative, and methodological issues, however contingently, is essential for elucidating patterns and trends and to define the field of inquiry for war and conflict in MENA. The data show several notable things. When viewed over the duration of the post-World War II era, the patterns of conflict in MENA are mostly unexceptional. MENA largely tracked with global trends in the frequency and form of war. War became rarer in MENA at roughly the same time as it became rare globally. War became more prevalent in MENA when it became more prevalent globally. The epidemic of internal wars in MENA roughly coincided with the global turn toward internal wars. As in other regions, war is not evenly distributed within MENA itself. Some countries, like Israel and Iraq, have experienced nearly perpetual war. Other countries in the region have seen only sporadic warfare. This suggests a need to consider the issue of war from both a global system and regional sub-system perspective.

In terms of magnitude of conflict, the data are far grimmer. For much of the second half of the twentieth century, it was wars in eastern Asia that claimed the most lives. However, since the turn of the twenty-first century, conflicts in MENA have been proliferating and intensifying. Most of the recent violence in MENA is broadly attributable to episodes of internal (civil) war and state failure. Yet states in many ways remain at the fulcrum of violence. The next chapter explores how contestation over statehood generates different forms of violence.

1 1. Fred Charles Iklé, Every War Must End (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005 [1971]), 35–6.

2 2. Alan Page Fiske and Tage Shakti Rai, Virtuous Violence: Hurting and Killing to Create, Sustain, End, and Honor Social Relationships (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

3 3. Jeremy Black, “What Is War?,” in What Is War? An Investigation in the Wake of 9/11, edited by Mary Ellen O’Connell (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2012), 177.

4 4. Peter Wallensteen, “The Origins of Contemporary Peace Research,” in Understanding Peace Research, edited by Kristine Höglund and Magnus Öberg (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2011); Barry Buzan and Lene Hansen, The Evolution of International Security Studies (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

5 5. Mary Kaldor, New and Old Wars, second edition (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2007); Siniša Malešević, “The Sociology of New Wars? Assessing the Causes and Objectives of Contemporary Violent Conflicts,” International Political Sociology 2, no. 2 (2008): 97–112.

6 6. John E. Mueller, Remnants of War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004); Jacob Mundy, “Deconstructing Civil Wars: Beyond the New Wars Debate,” Security Dialogue 42, no. 3 (2011): 279–95.

7 7. Edward Newman, “The ‘New Wars’ Debate: A Historical Perspective Is Needed,” Security Dialogue 35, no. 2 (2004): 173–89.

8 8. Stathis N. Kalyvas and Laia Balcells, “International System and Technologies of Rebellion: How the End of the Cold War Shaped Internal Conflict,” American Political Science Review 104, no. 3 (2010): 415–29.

9 9. Tarak Barkawi and Mark Laffey, “The Postcolonial Moment in Security Studies,” Review of International Studies 32, no. 2 (2006): 329–54.

10 10. Jack P. Gibbs, “Conceptualization of Terrorism,” American Sociological Review 54, no. 3 (1989): 329–41; Asafa Jalata, “Conceptualizing and Theorizing Terrorism in the Historical and Global Context,” Humanity & Society 34, no. 4 (2010): 317–49; Leonard Weinberg, Ami Pedahzur, and Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler, “The Challenges of Conceptualizing Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 16, no. 4 (2004): 777–94.

11 11. James Derrick Sidaway, “Geopolitics, Geography, and ‘Terrorism’ in the Middle East,” Environment & Planning D: Society & Space 12, no. 3 (1994): 357–72.

12 12. Rosa Brooks, How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything: Tales from the Pentagon (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016), 61.

13 13. Heritage Foundation, “Assessing Threats to US Vital Interests: Middle East” (2018).

14 14. Mirjam E. Sørli, Nils Petter Gleditsch, and Håvard Strand, “Why Is There So Much Conflict in the Middle East?,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 49, no. 1 (2005): 141–65.

15 15. John E. Mueller, “The Obsolescence of Major War,” Bulletin of Peace Proposals 21, no. 3 (1990): 321–8; Joshua S. Goldstein, Winning the War on War: The Decline of Armed Conflict Worldwide (New York: Penguin, 2012); Arie M. Kacowicz, Zones of Peace in the Third World: South America and West Africa in Comparative Perspective (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1998).

16 16. William Eckhardt, “Civilian Deaths in Wartime,” Bulletin of Peace Proposals 20, no. 1 (1989): 89–98; Adam Roberts, “Lives and Statistics: Are 90% of War Victims Civilians?,” Survival 52, no. 3 (2010): 115–36.

17 17. Madeline Edwards, “Syrian Author Khaled Khalifa on Latest Novel About ‘Fear, in All Its Manifestations’,” SyriaDirect, February 27, 2019, https://syriadirect.org/news/syrian-author-khaled-khalifa-on-latest-novel-about-%E2%80%98fear-in-all-its-manifestations%E2%80%99/.

Читать дальше