He still cries when he sees it.

Also in his desk is the bill from the hospital for the maternity services his mother received. A bill issued to her husband after her death.

Grandma Marjorie was survived by her baby girl, who was also named Marjorie. As a girl, Young Marjorie was red-haired and sparky. She worked on the farm, throwing herself into everything – baking with gusto and covering herself and the kitchen with flour, chopping logs and accidentally hacking her finger-end off with the axe. She got engaged to a local undertaker called John but Young Marjorie had a digestive disorder and no one realized how serious it was until she collapsed and died. Instead of being married in 1959 she was buried. This was four years before I was born. She was twenty-one.

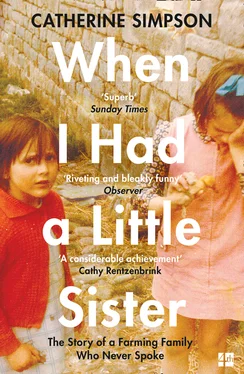

Young Marjorie, aged 21, the year she died

I think it was in 2005 that the Kilner jars of damsons, picked from the orchard and bottled by Young Marjorie, and that had been lining the far-pantry shelves my entire life, were finally thrown out.

It took me a long time to realize that Grandma Marjorie was so scarcely mentioned I didn’t have a proper name for her and had settled on ‘Dad’s Mum’. Stories about her were rare not because nobody cared but because Dad and Gran cared so much. On this subject, as on so many others, we were dumbstruck.

In my lifetime the cupboard halfway up the farmhouse stairs had been painted shut with layer upon layer of thick gloss paint. As a child I pressed my eye to the keyhole, shone in a torch and saw book spines untouched for more than twenty years.

Books were my escape from a world with the wrong kind of drama in it. I hungered for stories and books to make reality fall away.

I read to find circuses, wild animals, long dresses, castles, enchanted forests and magic faraway trees. Re-entering real life after being lost in a book was painful and disorientating.

At the table I read the back of the cereal packet. I read the primary-school library over and over again. I read the set texts Elizabeth brought home from secondary school: Animal Farm , White Fang , The Otterbury Incident . I read the Daily Express . I read the Radio Times . When I ran out of stories I read the dictionary. I compiled my own dictionary of words I didn’t understand. ‘Tippet: a woman’s shawl; Brougham: a horse-drawn carriage; Stucco: plaster used for decorative mouldings’ reads the list, in what must have been a Georgette Heyer phase.

Until sixth-form college my reading was unguided so I read Tender is the Night but not The Great Gatsby , Anna Karenina but not War and Peace , Lady Chatterley’s Lover but not Women in Love . I chose books from Garstang Library purely on covers and titles. I read the entire works of P. G. Wodehouse and Agatha Christie, fascinated by their versions of English country houses. I read everything Catherine Cookson wrote and pronounced ‘whore’ with a ‘w’.

My mother brought back library books in the Ulverscroft Large Print series for me, knowing I wore glasses without understanding they were for distance not for reading. Producing a child who needed glasses was perturbing for my mother: ‘I fell down stairs when I was expecting. I didn’t make such a good job of you.’ I never told her I could read small print perfectly well, because I liked getting lost in the great big words.

But my mother did give me occasional random compliments. ‘Your ears lie good and flat. The back of your head is well shaped. Your eyebrows suit your face.’

I was short of books and often panicked about it, so one day I prised open the cupboard door on the stairs as the hinges made sharp cracking sounds and splinters of paint flaked off. Inside were dusty and faded hard-backed books. I inched one out and shut the door, pressing the cracked paint on the hinges back into place. The book was Sue Barton, Senior Nurse and was signed on the flyleaf ‘Marjorie Simpson, 1956’.

I took it downstairs and sat on the hearthrug in front of the open fire. My mother said: ‘What’s that? It looks like rubbish.’ I struggled through a few pages but there was no adventure here; it seemed to be about nothing but a nurse in trouble with ‘Sister’ for being on the ward with her ‘slip’ showing. My mother was right, it was rubbish. I squeezed my hand again between the painted-up doors, scraping my knuckles as I put Aunty Marjorie’s book back in the past.

I have wanted to be a writer for as long as I’ve been able to read. I wrote my first book aged nine in a hard-backed Silvine notebook with marbled endpapers. It chronicled the adventures of ‘Sandra’ and ‘Barbara’ – two girls who apparently went everywhere (mainly to dancing lessons) on horseback and had a sworn enemy called Mr White. My best friend, Alex, and I acted out the adventures of Sandra and Barbara every day in the school playground.

My writing ambitions faltered after that because writing became embarrassing; self-indulgent and pointless, particularly after a boyfriend found something I’d written when I was a teenager and flicked through with a sneer on his face. ‘What is this? What do you think you are – a writer ?’ Later I discovered he had scrawled in the margin ‘This is stupid’, in case I hadn’t got the message.

My mother read gardening books, dressmaking books, yoga books and recipe books, but no fiction. She referred to fiction as ‘made-up stuff’, and asked ‘why do you read that ?’

I left school at eighteen with dismal A-level results and became a bank clerk then a civil servant, jobs taken for the sake of taking a job – because that’s what you did . I also had to pay the mortgage I’d saddled myself with aged nineteen – because buying a house was something else that you did . In my mid-twenties I retrained as a journalist because that seemed an acceptable way to earn a living with words. My mother died when I was forty-two and shortly after that I began to write pieces of fiction and memoir. It took me until my first novel was published, when I was fifty-one, to realize the death of my mother and the birth of my writing were linked – that in losing my mother I had acquired the right to write my own life.

After Tricia died the thought of what would be involved in clearing the farmhouse was terrifying.

A few years earlier I had viewed a house for sale in which the owner had died of a heart attack only days before and I had been appalled to see bread on the kitchen units that was still in date and the dead owner’s appointments on the calendar for the following week: Coffee with Bernard, 2 o’clock .

Families move at different speeds. Tricia had been dead six months when Dad said, ‘What about doing something wi’ yon house?’ and we knew we couldn’t put it off any longer. At first I thought we’d get a skip, but no, Dad built another enormous bonfire in the orchard – this time away from the telephone wires – and, bit by bit, we ferried generations of possessions onto what was in effect a funeral pyre.

Not knowing what to do with many things with sentimental value, we threw them into a ‘Memory Box’, actually a yellow cardboard box in which my new boots had just arrived.

These were the things we saved:

Tricia’s childhood jewellery: tangled silver chains, little charms and bent and twisted earrings; her drawings and paintings, watercolours of cats and dogs and horses and self-portraits; photographs of Tricia with friends we didn’t know in places we didn’t recognize. I studied her face, scanning her expression for signs of distress – did she want to be there? Was she enjoying herself or was she desperate to be alone, smoking? Was that a false smile? Was she suffering? Was that one of her good days or one of her bad?

Читать дальше