4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019

Copyright © Catherine Simpson 2019

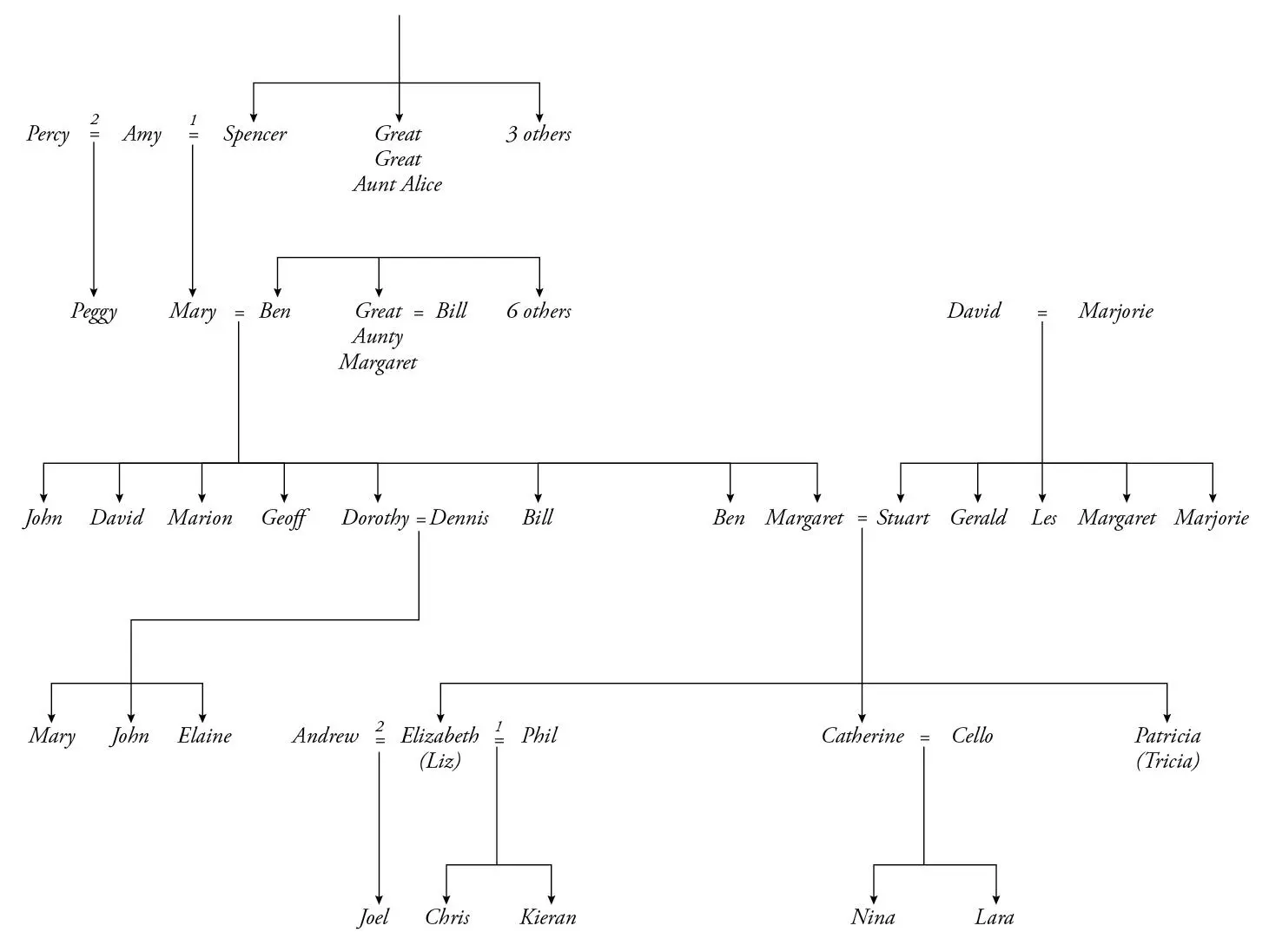

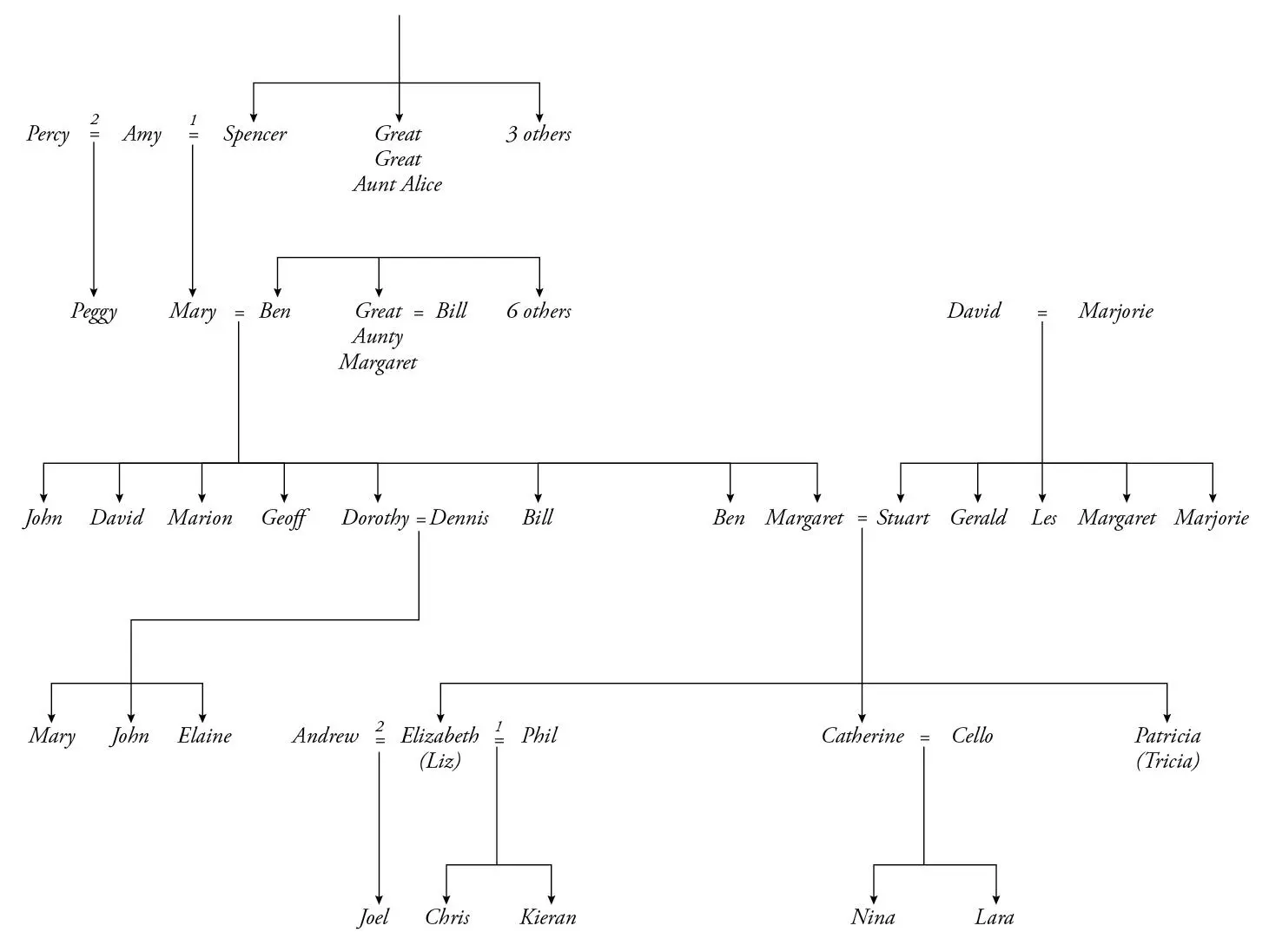

Family tree © Martin Brown

Catherine Simpson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All images supplied by the author, from her family collection. While every effort has been made to trace owners of third party copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers will be glad to rectify any omissions in future editions.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008301637

Ebook Edition © February 2019 ISBN: 9780008301651

Version: 2018-12-21

For

Cello

Nina & Lara

Mum, Dad

Elizabeth & Tricia

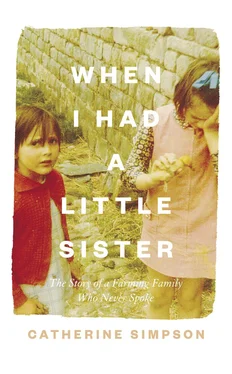

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Family Tree

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

New House Farm, the Simpson family home since 1925

Saturday 7th December 2013, late afternoon

I peer into the bathroom and from here the room looks like a tableau with the main character removed. On the wooden floor is a striped mug half-full of cold coffee. I move closer and see the milk cold and pale, risen to the top. Beside the mug is a packet of opened cigarettes, not Tricia’s usual baccy and Rizla papers, and next to that her blue plastic lighter. There are four floating dog-ends in the toilet bowl.

It is dark outside and gloomy in, and the house is filled with a terrible quiet.

Tricia must have sat on the bathroom floor with her back to the radiator long enough to smoke four cigarettes, dragging hard, taking the smoke deep into her lungs and holding it, holding it, for long seconds at a time, before blowing it out of the side of her mouth, eyes squint, then when she’d got down to the filters grinding out the butts and dropping them in the toilet bowl one after the other. She was smoking in the bathroom to help her cut down – she had banned herself from smoking anywhere else in the house because she wanted to be healthy.

On the night she died she was still trying to be healthy.

When did she decide to die? Was it before midnight on Friday the 6th, because she couldn’t face another night, or was it before dawn on Saturday the 7th, because she couldn’t face another day?

Did she think about us? Did she think about her dog, Ted, or her cat, Puss, sleeping on Grandma Mary’s old sofa in the conservatory and who would be waiting for her to feed them in the morning? What about her horses in the stable – Billy and Sasha – who she called her ‘babies’? Did she think about them? Did she imagine Dad finding her? It would have to be Dad, after all. It couldn’t be anyone else.

Did she know what she was doing?

Saturday 7th December 2013, earlier that day

A late start for the Christmas shopping. I call a friend and say let’s not bother buying for each other this year – I need to simplify. I’m tired; only back a day or two from a trip with my elder sister, Elizabeth, and 87-year-old father to the First World War battlefields at Ypres to see where my grandad fought in 1917. We’d planned it for Dad – he’d always wanted to go. We thought it would give him time away from the farm and be a break from worrying about our younger sister, Tricia – although he worried about her constantly anyway.

Now I am worn out and too tired for Christmas.

My husband Marcello, known as Cello, drives me to Haddington, a market town in East Lothian, to begin the Christmas shopping.

I choose turquoise leather diaries for both my sisters. I also pick out art supplies for Tricia: paints and pastels and a sketch pad. She likes painting and drawing. She is good at it.

There is a café in the shop and as a reward for starting the Christmas shopping Cello and I tuck into coffee and scones. We enjoy what I think of afterwards as the last bit of normal life for a long time.

As we leave the shop my mobile rings. I dump my carrier bags on the pavement and root through my rucksack. I can never find my phone. I hate my phone. I have an autistic daughter and over the years I have come to associate a ringing phone with trouble.

My screen flashes up ‘Johnny’, Elizabeth’s new boyfriend. I have only met Johnny a handful of times. I smile as I say hello.

‘Bad news, I’m afraid.’ His voice is urgent and there is scuffling at the other end as the phone is handed to Elizabeth. I prickle with fear and my body goes onto high alert. My breathing stops, my scalp fizzes.

What is it? I can feel my voice rise. What is it? It must be Dad.

Or Tricia. Which one is it? Dad? Or Tricia?

We have been living on a knife-edge for so long I know this is something big.

Elizabeth struggles to speak but eventually says, ‘I think something’s happened to Tricia.’ What’s happened? Elizabeth’s voice wavers. ‘Paramedics phoned from the farm. I think Tricia might be dead.’

It’s as though a great boot has caught me hard under the ribs – a knockout blow to the solar plexus – and my knees buckle. There is no breath left in me. I grip the shop’s windowsill and I am aware of the tinsel in the Christmas display twinkling at the corner of my eye as my face hangs over the pavement. The world sways and I have an urge to get onto the ground to feel secure, but do not. My husband grabs my arm. ‘What is it? What’s happened?’

‘It’s Tricia,’ I say, ‘Elizabeth thinks she’s dead,’ and I am unaware whether I am whispering or wailing.

‘Oh no,’ I hear Cello say again and again. ‘Oh no.’

Shock and grief are very physical and it will be weeks before I lose the sensation of reeling backwards, of staggering, unable to grasp onto anything sure and safe that will enable me to regain my balance and find my footing again.

Читать дальше