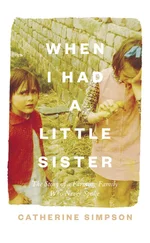

There were other items folded in big stiff carriers with the names of local boutiques on the side and with their labels still attached along with handwritten invoices for hundreds of pounds. So this was how Tricia had been spending her inheritance from Mum. There were clutch bags, large and small, in every colour. The wardrobe was full, as was the hanging rail which stood beside a full-length tilting mirror. It was a room devoted to glamour and beauty and femininity. I knew my sister was beautiful but I had not realized she possessed all these lovely things, or that she cared so much about her physical appearance.

Over the following months Elizabeth and I picked out pieces and took them home. Tricia was taller and more willowy than us, though, and one by one most of the outfits ended up at the charity shop.

My sister had shocked me by killing herself but maybe there were many things I didn’t know about her even though I had known her all her life, and almost all of mine. I had loved her. Things had been difficult as her mental health deteriorated, but I had always loved her.

All my life one gauge I used to decide if someone was acting unreasonably towards me was to ask myself: ‘Would I let them treat Tricia this way?’ I had always felt protective of her but in that I had clearly failed. I sat on the bed gazing in amazement at all these unfamiliar possessions – the possessions of a different woman altogether from the one I thought I knew – and I wondered: how well had I known her? How well can we ever know anyone?

As I sat in the farmhouse, dazed, the telephone engineer arrived to mend the phone. He thought the problem was a fault with an overhead wire, he said. He was standing at the back door and I told him what had happened the day before. His face became stricken and his eyes flickered over my shoulder as though drawn to witness the trauma. He picked up his enormous toolbag and headed into the garden to do the repair. An hour later he reappeared. It was all fixed, he said, but in future could we get Dad to build his enormous bonfires somewhere else. He gave me a meaningful look and cast a furtive glance towards the orchard, then mouthed the words ‘or they’ll charge him a fortune’, and with a tap on the side of his nose he was gone. An act of kindness from the telephone man seemed enormously significant. In those first raw days I latched onto all small acts of kindness and humanity.

We buried Tricia in her dressage gear – jodhpurs, fitted dark blue jacket, white shirt with a stock around the neck – and we put her riding crop in her hand. I never saw Tricia practising dressage, even though she had been doing it for some years, because she was shy about being watched. But I knew how much pride she took in it. I knew, on a good day, how enthusiastically she’d tell you about her ‘perfect trot–canters’ and her ‘flying changes’. My memories of Tricia riding were of the less-controlled variety. For instance, the first time she was put on the back of a friend’s horse, aged six or seven, and the horse bolted down the lane. I remember the screams of the friend’s mother and the panic followed by the relief when the horse was captured and led back – with Tricia still in the saddle, an enormous grin on her face.

As we prepared Tricia’s outfit, Alice, a lady from the village, showed me how to tie the stock so I could explain it to the undertaker. We couldn’t find Tricia’s stock pin so Alice went home and brought back a gold stock pin with a little horseshoe on it which strangely looked like a symbol of good luck. Elizabeth spent hours polishing Tricia’s riding boots to a glassy sheen, all the time aware that the undertaker might have to slice right up the back to get them on.

There was a line of framed photographs along Tricia’s mantelpiece in the farmhouse kitchen showing her Labrador, Ted, and her old collie, Roy, alongside pictures of her long-gone mare Hattie shoving her head over the denim-blue stable door. We took these photographs, and one of Dad sitting on the old water trough with Roy smiling at his feet, and placed them around her in the coffin.

It was months before I realized that the only photograph we left behind on the mantelpiece was one of the whole family together: my mum (Margaret), dad (Stuart), Elizabeth, Tricia and me, at a family wedding smiling in our Sunday best.

Dad, Mum, Me, Tricia and Elizabeth at Cousin Mary’s wedding

Maybe in choosing the photographs of her animals to go in her coffin – as her ‘grave goods’ – we had unconsciously acknowledged that animals were a constant source of comfort to her and had never let her down whereas we, her family, had.

The eventual emptying of the farmhouse after Tricia died, a job we put off again and again for months, was a huge task because my grandparents, David and Marjorie, had moved into the farm in 1925 and it seemed little had been cleared out since; consequently generations of belongings had composted over the years and it felt as though we were unearthing an architectural dig. The process of untangling our past called for decision after decision which seemed to accumulate in weight as we progressed.

In fact some of the clearing had been done, in 2005, eight years before Tricia died, when we sold the old barns for development. At that time the great hay barn, the cowsheds, the old stables and pig pens had to be emptied of what amounted to my mother’s ‘overspill’. My mother was a shopper. In particular she was a shopper of wool and cloth, sewing paraphernalia and gadgets. She loved gadgets for cleaning, gadgets for cooking, gadgets for sewing and knitting. My mother had an eagle eye for advertisements featuring anything newfangled that came with an instruction book – things that made big promises about saving time and labour – and she would seek out these expensive gadgets and buy them. Her idea of a birthday outing was a drive to Lakeland Plastics in its original Lakeland home to buy more gadgets.

When it came to the clearing of the barns in 2005 we were faced with chest freezers and suitcases and cardboard boxes full of mouldy wool and bolts of cloth still with their labels attached showing the size and price – which was always startlingly high – plus baffling gadgets that had never been assembled: gadgets for cleaning windows, steaming carpets, cutting out dress patterns, assembling quilts and knitting complex designs.

Anyone would think my mother enjoyed cleaning and housework, but this was not true; in fact she despised the excessively house-proud. She liked to declare that only boring women had tidy houses. I suppose her constant purchase of gadgets for cleaning was a way to make housework more interesting, or at least put it off for a while in favour of another shopping trip. But she adored handicrafts and, after packing the farmhouse to the gunwales with cotton bobbins, buttons on cards, zips in every colour and endless dressmaking patterns, as well as the wool and cloth, she set to filling the barns and outhouses with her haberdashery as well.

In the year 2000 Mum and Dad moved out of New House Farm to a newly built dormer bungalow up the lane. Tricia was left to live alone in the farmhouse, much to her satisfaction, although she was less thrilled when she realized the house was to be left still packed with stuff because, as it turned out, although my mother had moved she still reigned supreme – now over two houses – and her possessions left behind in the farmhouse and barns (until the barns were sold) must not be touched . Meanwhile Mum set about filling her new house with stuff too.

My mother’s mood – often low and downbeat – could be transformed by ‘newness’. She was excited by technology and innovation. She bought shares in the Channel Tunnel as soon as it was possible, went to ‘computer classes’ before I ever did, and invested in bio-tech companies, enthusiastically telling you which diseases her investments were about to cure. She was dismissive of self-appointed gurus who advised you on how to live your life (‘Huh! Who says? Experts!’) but admired inventors and scientists.

Читать дальше