Then I deleted the photograph.

Death is a thousand tiny losses and each loss is a thousand tiny details.

Why was it important to get everything right for my mother as she lay in her coffin? It was guilt, I think – guilt that I couldn’t do anything else for her, guilt that I couldn’t bring her back, guilt that I had not been able to stop her dying in the first place. My mother had an enormous ability to make me feel guilty even when I had no idea what I should feel guilty about.

Years later I discovered that items placed in a coffin have a name: grave goods. Apparently people tuck all sorts around the dead: jewellery, photographs, sealed letters, rosary beads, spectacles, hats, mints, walking sticks, cigarettes, football strips, teddy bears, comfortable shoes and money.

For whose benefit are grave goods? Maybe mourners believe the item will help the dead on the journey to the afterlife – the walking stick, money, glasses and shoes. Or perhaps some items are considered part of the deceased’s identity, things that they should never be parted from – in particular the glasses. Or do grave goods in the coffin give the living a sense of comfort?

I think so.

In fitting my mother up with a bag and glasses and notes and her fanciest dress I took comfort from having done the best I could.

We arranged to bury Mum in the local village churchyard, a row further on from her own mother and father. We explained this to the undertaker at a meeting in Dad’s kitchen. The undertaker took notes on a clipboard and my father said, ‘Dig it deep and leave enough room for me,’ and Tricia, speaking up for the first time since the meeting began, said, ‘Dig it even deeper and leave enough room for me too.’

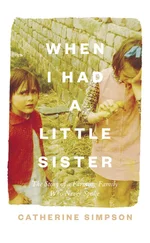

Every wall, every gateway and every tree on the lane leading to the farmhouse held a memory of Tricia. On my right was the wooden fence we leaned on to watch the mating ducks when she was five or six. ‘What they doing?’ she asked. ‘Makin’ friends,’ I said. On my left was the verge where our neighbour parked his flatbed truck – our stage for the plays I wrote, heavily influenced by Enid Blyton, in which I cast Tricia and Janet-from-next-door, mainly as dolls or fairies. (Play: A Lot of Rice for Tea ; Characters: Rag Doll, Dancer Doll, Fairy Doll, Dolly Doll and six ‘Chinease’ Dolls.)

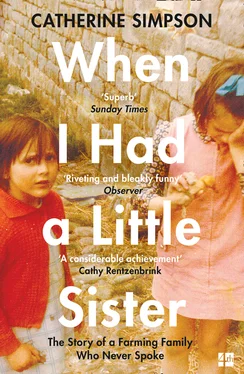

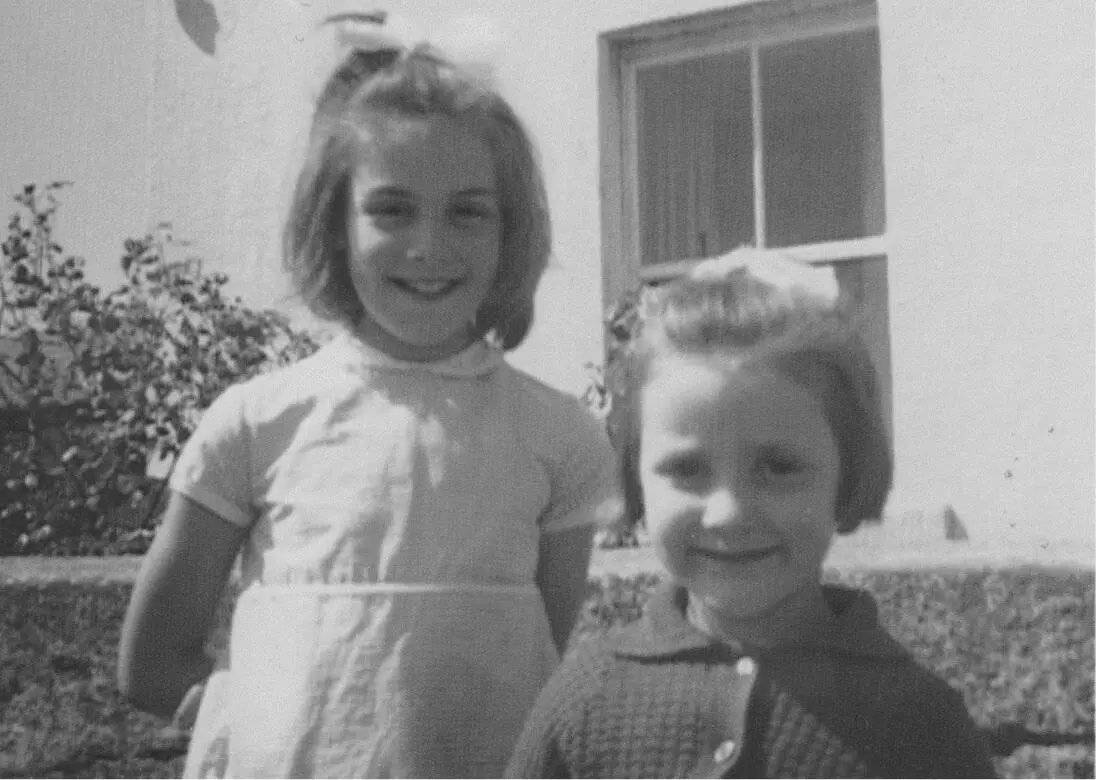

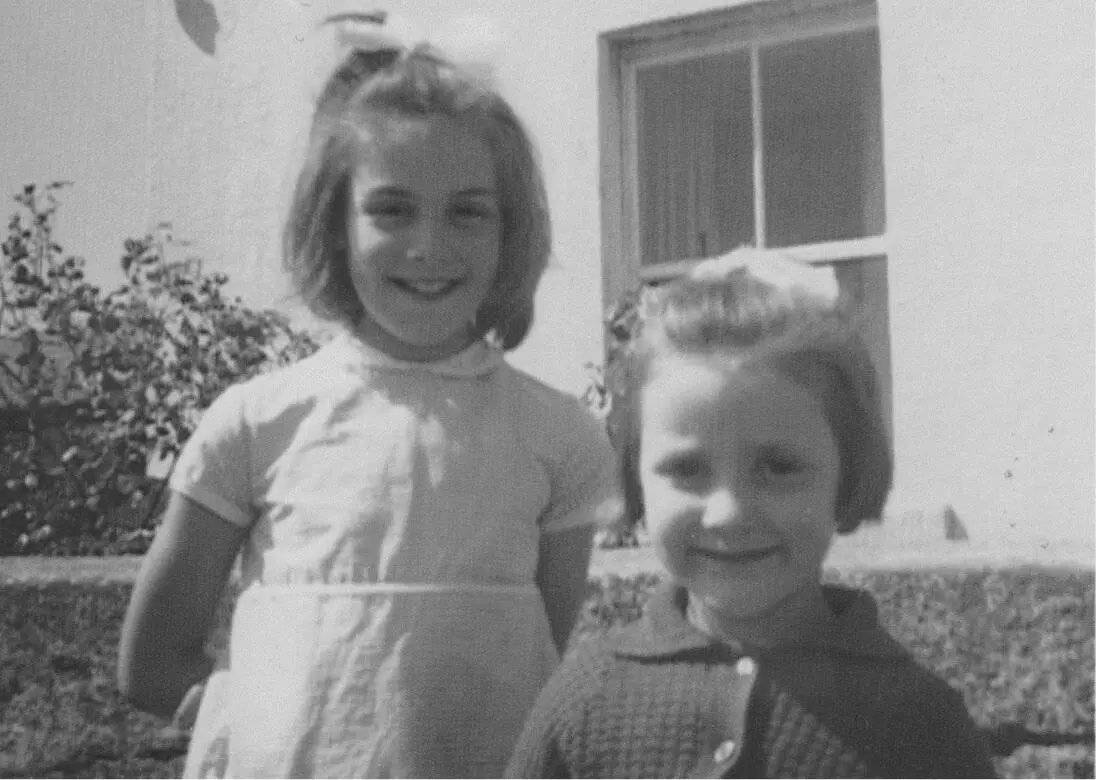

Me and Tricia in front of the wall we used as a stage and a catwalk

Past the verge was the head-high yard wall we balanced along for ‘playin’ bally’, never having had a ballet lesson. We took turns wearing a dog-eared 1950s evening dress donated to the dressing-up box by Great-Aunty Margaret and we ‘did twizzers’– arms outstretched and on tiptoes – until we legged ourselves up. At right angles was the stone garden wall we used as a stage to play ‘Miss World’, during which we draped ourselves in stuff from Mum’s ragbag. Elizabeth was compère and held a spoon or a drumstick for a microphone – ‘And in national dress, please welcome Miss Guam’ – as I set off down the wall wearing a 1940s tea-dress tied round with a tablecloth. ‘Next up, in her evening frock, it’s Miss Ceylon,’ and Tricia tottered down the wall wearing her vest, with a 1920s shawl around her waist and bits of broken chain-belt in her hair. On one occasion we used the wall as a catwalk for a fashion show with dresses we made from old cow-feed sacks, with holes cut for heads and arms and tied up with bale twine. The sacks made a ‘mini’ for Elizabeth, a ‘midi’ for me and a ‘maxi’ for Tricia, and left us covered in hundreds of tiny insect bites. We sampled the cow food-pellets – finding them salty and gloopy when chewed – but tried to forget about that fifteen years later when mad cow disease was all over the papers.

The day after Tricia died I was drawn back down the lane from Dad’s to the farmhouse, by a sense of disbelief, I think – a sense heightened by the many surrounding memories. The mortuary was closed for the weekend so I had not yet visited her body and I needed evidence it had happened; to see Tricia’s world without her in it, to check she was really gone.

Tricia beside the knicker bush, dressed as ‘Miss Ceylon’

Inside, the house smelled of stale tobacco – a smell that hit me then like a punch and still does. To me the smell of stale tobacco is the smell of anguish and hopelessness.

I stood at the door of the bathroom with its cold coffee and cigarettes on the wooden floor by the radiator. I moved about the house where I was born, a place that since yesterday had become the place Tricia had chosen to die.

In the living room I saw the lights were lit on the CD player. It was playing with the volume turned down – Tricia must have left it on a continuous loop. I squatted down to turn it up and the room filled with the pure, clear voice of Alison Krauss singing ‘When You Say Nothing At All’. The suddenness knocked me over and from a squatting position I plumped sideways onto the carpet.

In the kitchen I found the bin full of her long dark hair. I stared at it; so unexpected. She must have chopped it off last thing before she died because there was nothing thrown on top. Why had she cut her hair off? I did not reach into the bin and rescue a lock because the sight of her lovely hair there among the teabags and the soup tins reeked of despair and I couldn’t bear to touch it. Her long hair had been one of her trademarks ever since her early teens. There had been the occasional perm in the 1980s and it got shoved into a woolly hat when she was milking the cows or working with the horses, but it had never been anything other than long and dark and glossy, and now here it was tossed in the rubbish.

On the kitchen surfaces I found boxes and boxes of lotion for getting rid of hair lice. Tricia did not have hair lice; at that stage she didn’t have close enough contact with anyone to catch hair lice. I examined the boxes, baffled and heartbroken because these boxes reeked of despair too.

I learned later that a symptom of psychosis can be the sensation of a crawling on the skin that is impossible to alleviate. Memories of those boxes, and knowledge of the effort it must have taken Tricia to get out of the house and buy them for a problem she believed she had, swim into my mind often and have crystallized into the very image of loneliness.

I went into her bedroom but hated to look at her bed with the sheets and quilt in a tangled heap and some of the last items of clothing she had worn discarded on the floor. Signs of activity made her seem so close and underlined how recently she had been alive, how recently we should have been able to save her. The finality of death and the knowledge – although still not the belief – that she had gone shocked and re-shocked me over and over again every time my eyes alighted on some other personal item: her bedside glass of water, her toothbrush, her gum shield for stopping her grinding her teeth as she slept. The air was thick. It was as though the house itself was holding its breath.

I pushed open the door of my childhood bedroom – the familiar rattle of the latch, the whoosh of the door over the old shag-pile carpet – only to discover it had become a dressing room full of beautiful clothes. Tricia had been a farmer and a horsewoman; I remembered her in jeans and jumpers and grubby jackets with bits of straw clinging to them or maybe in a boiler suit, the top pulled down and tied round her waist as she wore a T-shirt in summer. This room used to contain two single beds and an ugly chest of drawers; now it appeared to contain a wardrobe and hanging rail stuffed with posh frocks. I found it hard to take in. I walked into the room and touched the hanging clothes. I could see a black satin halter-neck covered in red and yellow orchids and a black chiffon minidress with beaded cuffs, and alongside them were linen skirts, wool coats, silk blouses, fitted jackets, piles of scarves in every shade and texture, shelves of extraordinary shoes: gold sandals, red silk sandals, purple suede peep-toes, silver wedges and sparkly stilettos.

Читать дальше