Further north the kings of the Scots pursued their own imperial project, with the same vigour with which they defended their independence from the English. James IV fought long and hard to bring north-west Scotland under the control of Edinburgh. One of the most iconic castles in Britain, Urquhart, teetering on the edge of Loch Ness, was strategically vital and constantly changed hands between the Scottish Crown and the Lords of the Isles who dominated the north and west highlands of modern Scotland.

Eastern Europe, meanwhile, became a giant frontier between Christendom and the pagan, often nomadic, tribes of the steppes. The ‘Teutonic Knights’ who began operating in the Crusader States of the Holy Land pursued God’s enemies instead in the north-east of the continent, helping to convert (and conquer) Prussia on the Baltic coast. Behind them they left towering castles in red brick – strongholds like Malbork, which allowed them to dominate the region and to grow rich off its trade ( see Chapter 5). The German brickmakers and engineers that they used were some of the most proficient in Europe, and further west, in Germany itself, it was said that there was a castle to every square mile, helping to frustrate the ambitions of anyone who sought to unify the hundreds of autonomous statelets, bishoprics, margravates, duchies, and the like which covered central Europe in a bewildering patchwork.

By the time Malbork came under siege in 1410, a new technology had emerged which radically changed the way castles were built, and attacked. Gunpowder, invented in China around the ninth century, gradually spread west. By the late fourteenth century it was used widely in Europe. In 1453 the Hundred Years’ War was brought to a successful conclusion by the French at the battle of Castillon, the first pitch battle in European history in which cannon played a decisive role. Weapons now existed which could pound even the mightiest walls into dust: a development which in turn triggered a series of changes in government, society and fashion, and which led eventually to the eclipse of castles.

As improvements were made to gunpowder itself, and to the weapons it powered, artillery became ever more dominant. It was also, however, vastly expensive. Effectively, only those with access to the public purse could afford to use cannon, which became the weapon of kings. This significantly undermined the autonomy of the provincial aristocracy. No longer were they free to act as petty kings behind impenetrable walls. During the civil war in England in the fifteenth century, known as the ‘War of the Roses’, even the greatest castles in the land were eventually battered into submission. Bamburgh, which had been thought to be impregnable, fell when two cannon named ‘Newcastle’ and ‘London’ smashed a breech in its walls in 1464. Dunstaburgh, Alnwick and even Harlech all fell, though Harlech had held for seven years.

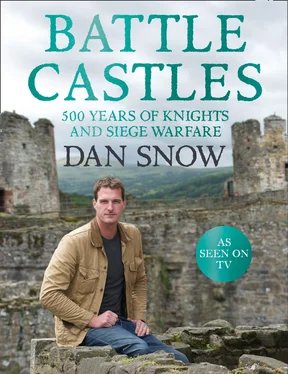

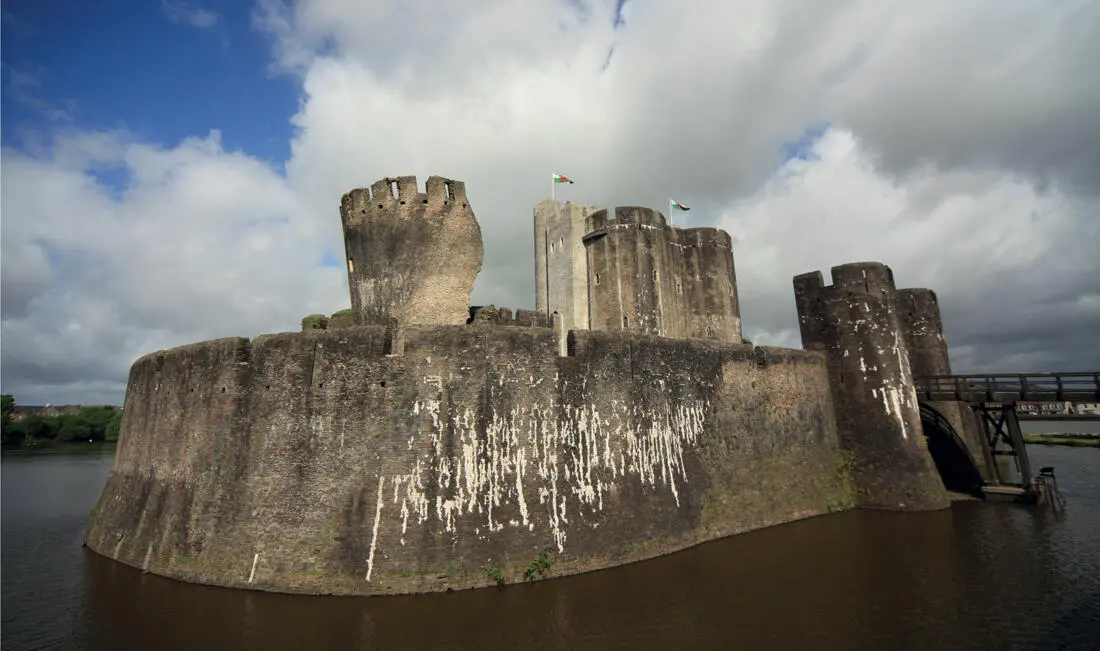

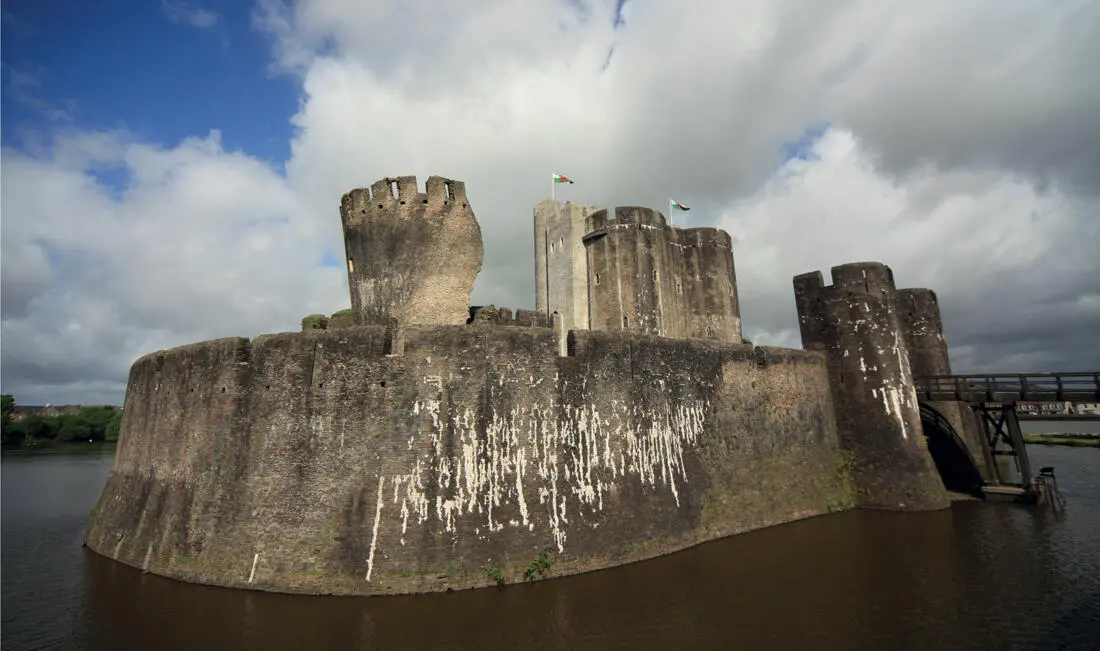

The middle and inner wards of Caerphilly Castle in south Wales which was not a royal project, despite its size. The leaning tower (centre-left) was a product of damage during the English Civil War

Bolstered by the power of gunpowder, the nature of central government changed in Western European kingdoms like England, Scotland, France and Spain. The Crown has less need for a military elite, with private armies ready at an instant to march against enemies domestic or external. Instead, the ability to tax their subjects to pay for musketeers, artillerymen or ships carrying heavy guns became paramount. Strong regimes emerged which showed a determination to gain a monopoly on the use of military power. Courtiers, administrators and lawyers were required, not warlords. The court travelled less as government grew more complex and immobile. The elite came to the court, not the other way round. Courtiers built comfortable houses and palaces using sophisticated new building techniques and materials like glass which were more enjoyable to inhabit and also embodied their status within a modern political system.

Castles survived. Many people continued to regard crenellations and fortifications (however fake) as the hallmarks of aristocracy. A few people even continued to build them, but these modern castles were subtly different from their stark Norman predecessors. A castle like Bodiam in Sussex was built as a stately home in the architectural style of a castle, but with its shallow, easily drainable moat and its windows in the curtain wall it would not have withstood a siege. Edward III spent a vast amount of money on Windsor Castle in the mid-fourteenth century, none of it on improving its defences. Instead he built palatial accommodation for himself and his queen and a set of buildings in the lower bailey for his new Order of the Garter. His son John of Gaunt entirely rebuilt Kenilworth Castle with comfort uppermost in his mind and Carew Castle saw its powerful defences hobbled by the renovations of its owner at the end of the fifteenth century.

In Scotland, the Stuart dynasty slowly eroded the power of the local elites. King James II was a great fan of artillery. He reduced several castles and increased the power of the Crown before being killed by an artillery piece exploding next to him at the siege of Roxburgh in 1460. Buildings were still built that look like castles – such as Borthwick, south-east of Edinburgh – but in reality they were indefensible. (Borthwick has beautiful machicolations but no crenellations, so anyone actually trying to use them to defend the castle would be exposed to the enemy below.)

Osaka Castle was raised in the sixteenth century. The siege in 1614–15 is considered by many to be one of the most important events in Japan’s history

Jose Fuste Raga / Getty Images

In Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, who completed the Reconquista or removal of Islamic rule from Iberia in 1492, ordered all the castles in the realm to be handed over to royal control. Although this was only partially enforced, they did order the destruction of many of them. There could be no more tangible a symbol of the assertion of royal, central control over the periphery.

The process was not irreversible, of course, nor was it universal. Far-away Japan saw a surge in castle building during the anarchic Sengoku period which lasted for around 150 years from the mid-fifteenth century onwards. From this maelstrom of violence a very similar military caste to that in the West came to dominate Japan. Showing a remarkable synchronicity, they chose castles as the totems of their power. It was centuries before central government was able to assert itself fully. The capture and destruction of Osaka Castle in 1868 was a hugely symbolic end to the period of rule by the military elite and a resurgent central government confiscated thousands of castles, destroying around 2,000 of them.

The British Isles would also see one more rush to fortify as its three component kingdoms descended into a bitter, unanticipated civil war in the seventeenth century. Old castles were suddenly reoccupied and modern earthworks were added. Taking the lead from Italy, fortifications were built with a low profile and arrow-shaped bastions projecting from the walls denying enemy cannon a clear shot at a towering wall. Huge earth ramparts were erected to deflect cannon balls, and complex geometric shapes were adopted to maximize fields of fire of the defenders. King Charles I’s followers fought supporters of Parliament in a drawn-out conflict as these new strongholds sprang up across Britain. With modern improvements to their defences, many medieval castles proved a match for the ad hoc artillery trains of the Parliamentarian forces. Castles like Basing House, Raglan and Pontefract proved a serious obstacle to final Parliamentarian victory. As a result the new Commonwealth regime that succeeded the deposed and executed King Charles ordered the destruction or ‘slighting’ (weakening) of some of the finest castles of the medieval world. Pontefract was wiped off the face of the earth, Nottingham and Montgomery were destroyed. Corfe, Caerphilly and Kenilworth were slighted. Thankfully castles deemed important for coastal defence were left standing. Dover, Arundel and Rochester are evidence of the new regime’s fear of foreign intervention.

Читать дальше