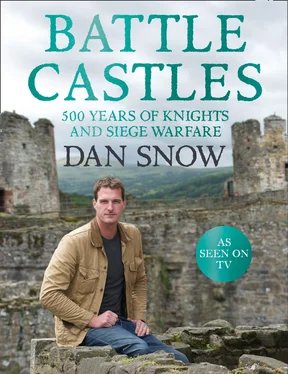

Pevensey was one of the first sites to be fortified when William the Conqueror came to England. Under the Normans it was updated to include a stone keep

Robert Harding World Imagery / Getty Images

Rarely in history has an annexation proved so enduring. The Norman grip on England held strong and Norman influence and power slowly spread, with varying success, through Wales, Scotland and Ireland. By the twelfth century, one chronicler referred to castles as ‘the bones of the kingdom’. But the warlords with their mighty castles that underpinned this dominance brought their own problems. Castles had begun as a response to the breakdown of central control, and a lord in his castle was a king in his own domain. To live in a castle bred, and still breeds, an independence of spirit, a suspicion of distant rulers or central government. Conquest and occupation was led by an active warrior king, but it was often enforced by a patchwork of local, autonomous warlords. To a king of William’s stature this was not a problem, but to his successors, castles, and the men who guarded them, would often prove less like bones that gave kingdoms their integrity, and more like rocks on which the ship of state could founder.

William’s descendants would learn that castles were loyal only to the men who held the key to their gate. His son, William II, was immediately faced with a rebellion by his father’s greatest nobles, who preferred the prospect of his brother’s rule. He was forced to conduct a gruelling siege of Pevensey Castle, once the symbol of his family’s claim to the English throne, as well as sieges of other castles, before a mixture of generous promises and the non-appearance of his brother’s army allowed him to secure the throne. Castles were the weapons of occupation, but not the tools of orderly royal rule.

Across Europe similar trends were seen. As the principalities of Western Christendom chipped away at the ring of pagans and Muslims that surrounded them, they built castles on their expanding frontier zones. Against the English, William the Conqueror had believed himself to be on a Crusade, carrying the Pope’s banner into battle. The Pope encouraged this, knowing that the English Church was frustratingly insubordinate. In Iberia, the Baltic and Eastern Europe, relatively small Crusader forces would annex land and then lock it down with a network of castles exactly as William had done in Britain. The Christian toehold in the north of the Iberian peninsula, initially part of the Frankish kingdom, first broke away from French control and then became a base for the conquest or ‘reconquest’ of the rest of modern Spain and Portugal. In Catalonia, in the far north-east, the massive castle of Cardona and the magical Quermançó Castle, built in the late eleventh century on a dizzying rocky outcrop, are testament to a refusal to be dominated by their neighbours – Christian or Muslim. Further south, the sprawling central area that would become the Kingdom of Castile was so defined by castle building that its very name was derived from them. Desperate to cling onto their gains, Crusaders built castles relentlessly – and their Muslim opponents did too. At Málaga, on the peninsula’s southern coast, the great castle of Gibralfaro – clinging to a hill above the town – would prove one of the last bastions of resistance against the resurgent Christian armies ( see Chapter 6).

Other Christian Crusaders pushed north and east. The warlike Normans travelled widely, building castles as they went. As William was crossing the Channel, his countrymen travelled also to southern Italy, first, it seems, as religious tourists, then as land-hungry warriors. Men like William de Hauteville, who won the nickname ‘Iron Arm’, arrived as adventurers and died as sovereigns. His half-brother Robert invaded Sicily and built San Marco d’Alunzio, the first Norman castle there, before capturing Rome itself.

Margat Castle’s black walls contrast starkly with the white limestone of Krak. Built of hard basalt, it was one of the Knights Hospitallers’ most important strongholds

In November 1095 Pope Urban II proposed a military expedition to ‘recover’ Jerusalem, the holiest site in the Christian faith – a call which unleashed wars of terrible ferocity across Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Kingdoms and principalities were carved out, besieged, captured and recaptured. In what was already a heavily-fortified landscape, the Christians built the most perfect castles in the world: Kerak, Krak des Chevaliers, Marqab and Saone to name a few ( see Chapter 3). To visit them today is a truly awesome experience. At Saone, now known as Salah Ed-Din’s (Saladin’s) Castle after the Egyptian military genius who eventually captured it, there is a 30-metre-deep ditch cut into the rock either by the Crusaders or their predecessors, guarded by a monumental Crusader bastion with walls 5 metres thick. As I approached these castles, panting in the heat, the walls seemed to grow ever more formidable. I was overwhelmed by the lengths to which the Crusaders went to protect their conquered territory. But I also could not help thinking that these vast edifices bear witness to the fury and vigour with which the Muslims tried to drive them back into the sea.

With a supply chain stretching over thousands of miles, a hostile unfamiliar climate and a dizzying array of enemies close by, these castles were needed as ‘force multipliers’ more than anywhere else. Despite the utterly different terrain, they were doing the same job as castles everywhere else I had visited. A group of armed outsiders, invaders, surrounded by hostile territory, sought refuge and strength behind stone walls, gatehouses and towers. The process was universal. I saw the same thing in Syria that I had in Wales, France and Spain.

In the West, war and anarchy continued to promote the building of castles. When King Henry I of England dared to die without a male heir, despite having fathered over twenty acknowledged illegitimate children, England was again plunged into chaos. Camps formed around his daughter Matilda and her cousin Stephen. War followed. Local lords looked to their own defence. Fortifications were raised. ‘Christ and all his saints were asleep,’ a chronicler observed, and ‘the land was filled with castles’.

Castles appear to have made civil war all the more intractable. Neither side had the resources to besiege their enemy’s castles one after the other and so two competing weak regimes were eclipsed in the provinces by local powerbases. For the first time in British history, sieges really came to the fore. During a siege of Newbury Castle, Stephen demanded the surrender of the garrison and said if they held out he would hang the son of their defiant leader in broad view. The warlord defied this threat: ‘I still have the hammer and the anvil,’ he declared, ‘with which to forge still more and better sons!’ Fortunately for the child, and fortunately for England, Stephen did not carry out his threat. The boy, William, would grow up to become the supreme English knight of medieval history, the Marshal of England and saviour of the kingdom at its lowest ebb. Matilda herself was no less lucky if folklore is to be believed. Twice she escaped from being besieged, once across the frozen Thames in winter in a white cloak, and once as a corpse being taken out for burial.

The so-called ‘Anarchy’ came to an end when Matilda’s son Henry Plantagenet invaded England from France in 1153, and forced the ageing Stephen to negotiate. The death of Stephen’s heir opened the door to a deal and Stephen named Henry as his successor. Through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II would control a vast empire from the borders of Scotland to the Pyrenees. To secure it he tore down troublesome castles and built mighty royal ones, like that at Dover which rose above the white cliffs and which would endure the attacks of Prince Louis, another claimant to the throne of England ( see Chapter 1).

Читать дальше