Henry spent vast amounts of money on his royal castles. It was not unusual for half the annual royal budget to be spent either on building new castles or repairing old ones. An eyewitness observed of the building work at the Tower of London that ‘with so many smiths, carpenters and other workmen, working so vehemently with bustle and noise […] a man could hardly hear the one next to him speak’. Under Henry we know that an unskilled labourer moving earth and stones on a site like this would have been paid a penny a day. For the King these castles were about prestige as much as security. Dover was a glittering adornment to the channel coast, visible to ships passing through the narrows, a symbol of Henry’s massive empire. It was also one of many seats of government. Medieval kingship was peripatetic: kings and courts moved constantly. Since rule was personal it was wise for a king to show himself to his subjects, dispense justice and redress grievance as widely as possible. But logistics also played a part. The King and his court soon consumed all the supplies in one castle and it was easier to move to the food than to bring the food to them. Henry would have recognized the description of medieval kingship offered by his namesake, Henry IV, King of France: ‘I rule with my weapon in my hand and my arse in the saddle.’ His royal castles really were residences for him and his court on these huge progresses and they were appointed with all the finery demanded by the royal court.

The castles also served their most obvious purpose. When Scottish King William the Lion invaded England in 1173, he marched on Newcastle but did not even attempt to besiege the castle because he lacked the necessary, cumbersome siege engines. When he tried to besiege Alnwick, he was captured by English knights and eventually forced to sign a humiliating submission to the English Crown. Henry’s castles defended his northern frontier while he focussed his attention on unrest in other parts of his empire.

That empire grew wider: Ireland was sucked into the orbit of the Plantagenet Crown when Henry himself invaded and captured Dublin, and received the submission of its bishops and kings. Castles like Kilkenny, Killeen and Dunsany were planted by Henry’s subordinates, and his son, John, started work on Dublin Castle, a building that was to remain the seat of English and then British rule in Ireland until 1922. Ireland remained largely beyond the writ of English government, however, as other targets distracted English kings. It was never fully annexed, the chronicler Gerald Cambrensis lamented, because of the failure to build castles ‘from sea to sea’.

Henry’s sons utterly failed to guard their vast inheritance. Richard was a warrior, but no ruler, and John may have been a ruler, but he was no warrior. Richard died while pressing home the siege of a castle in France. His younger brother John’s reign saw Philip of France pushing to expand his kingdom at the expense of Plantagenet lands – laying siege, most notably, to Château Gaillard, the extraordinary castle Richard had built above the small town of Andely, on a bend of the River Seine ( see Chapter 2). Failure and losses in France led to unrest in England itself, where rebels tried vainly to hold out in Rochester Castle (‘Living memory,’ a chronicler wrote, ‘does not recall a siege so fiercely pressed, and so staunchly resisted’). The French intervened in this English civil war and the loyal knight Hubert de Burgh led King John’s garrison at Dover in defiance of Prince Louis’ invading army ( see Chapter 1).

The years following the death of Henry II witnessed a protracted struggle about the nature and limits of kingship, and castles were the physical manifestation of an aristocracy that felt themselves more than simple subjects. John, his son Henry III and even Henry’s warrior son, Edward, were no strangers to being besieged and even captured by rebels. Eventually the monarchy, in the person of Edward I, emerged victorious, but only after he had promised to abide by the restrictions placed on his grandfather and father by the Great Charter or Magna Carta.

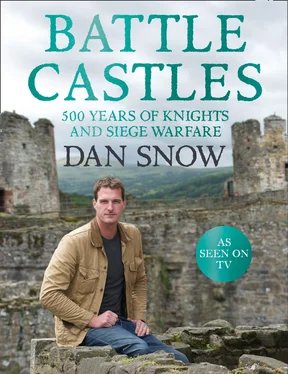

Edward’s peace within England lasted long enough to turn his attention to unfinished business in the rest of the British Isles. Edward fought several campaigns in Wales, initially punitive but eventually of outright conquest. As always, castles were to be the method of subjugation. Edward spent a staggering £80,000 in twenty-five years, considerably more than his father had spent on the magnificent Westminster Abbey. Edward’s engineers built castles that are regarded around the world as some of the finest ever built, including Harlech, Caernarfon, Beaumaris and Conwy – a ring of steel around the recently-independent mountain region of Gwynedd in north-west Wales. To this day, a castle like Conwy dominates its surroundings. Caernarfon was built on a site with powerful Roman associations, and in its architecture and brickwork it deliberately echoed this earlier empire. This was Edward staking his claim to be the modern incarnation of the Caesars, just as his ancestor William had done centuries before. The Welsh understood the message, and when they rose in rebellion, it was these castles – symbols of hated English rule – that were a prime target ( see Chapter 4). King Edward attempted to bring Scotland and Wales under the English Crown and yet again castles were used to enforce occupation. Scotland already had a wide network of castles built by Anglo-Norman settlers who had integrated themselves at the Scottish court through marriage and service to the Scottish Crown. These castles Edward sought to control as his forces dealt with widespread rebellions across the countryside led by William Wallace and Robert the Bruce. The Bruce knew just how important these castles were and rarely lost a chance to ‘slight’ or render them defenceless by collapsing an important section of wall. Scotland was never truly pacified by Edward, who died on his way north to deal with the latest of the Bruce’s victories.

As the chapters in this book explain, the design for these castles had evolved greatly since the arrival of the Normans in England. The key defence was no longer, as at Dover, a central keep, but the outer layers. Towering walls, lofty round towers and a massive gatehouse were in vogue, allowing the interior to be laid out with palatial magnificence. The gateway had always been a weak point, but by the thirteenth century changes had made it almost the strongest point of the castle. Round towers on either side in castles like Framlingham in Suffolk or Caerphilly in South Wales were pushed forward with embrasures, allowing the defenders to rake the entrance with crossbow bolts and arrows. Above the gate murder holes and ‘machicolations’ could be used to pour boiling water or incendiaries on the attackers below. Some castles were given a barbican or additional defensive layer in front of the gates, which might be offset to prevent an attacking force using a battering ram.

Scotland eventually secured independence thanks to a crushing victory at Bannockburn in 1314 in the shadow of Stirling Castle, held by the English, besieged by the Scots, and the key to central Scotland. Castles played a huge role in the nature of Scottish kingship thereafter. A geographically-disjointed state with a poor central treasury, Scotland had little choice but to delegate political authority. Lords ruled isolated areas with the powers of kings. Castles were the choice of these aristocrats, partly because Scotland was occasionally torn by civil strife (although it does not seem to have been endemic as was once thought), but partly also because of fashion. The Bruces, the Comyns, the Balliols all had Anglo-Norman blood, owned land in England, and employed the same architects and engineers as their peers had south of the border. Their castles reflected their status as demi-kings: in their own lands dispensers of justice, collectors of revenue and protectors.

Читать дальше