consumed by age, Earth-grip holds

the proud builders, departed, long lost,

and the hard grasp of the grave, until a hundred generations

of people have passed. Often this wall outlasted,

hoary with lichen, red-stained, withstanding the storm,

one region after another; the high arch has now fallen.

The wall-stone still stands, hacked by weapons,

by grim-ground files.

Along with Roman infrastructure, the written word, the scrolls of study, were largely lost, at least in the West. As the natural science of the Greeks and Romans faded and almost disappeared, some ‘stories’ written in the 3rd century survived and became part of the early medieval world view. One such work was the product of Caius Julius Solinus, whose speciality was the study of grammar. His book A Collection of Memorable Facts comprises 1,100 descriptions that range from direct biblical descriptions to tall tales of Africa where the shadows of hyenas robbed dogs of their ability to bark. It was a great collection of myths – exaggerated travellers’ tales borrowed from many previous authors, with just enough geographical reality to give this masterpiece of disinformation a kind of believable life of its own. In the 6th century it was revised and republished under the title Polyhistor , meaning ‘many stories’.

The Christian faith spread around the Mediterranean from its place of origin in Palestine. It was a religion that, in a changing world occupied by usurpers, barbarian invaders, plagues and famine, offered at least the promise of a better life in the next world – the afterlife. The prevailing Greco-Roman religion did not offer any of that – it demanded sacrifice. The cults offered no guidance for the living of a good life; the underworld was not a place of peaceful eternity.

The Christian world still had a place for the Devil and leagues of demons. By the Edict of Thessalonica, 380 CE, Christianity was confirmed as the religion of the Roman Empire. Now, with official sanction, the new faith began its work: the suppression of pagan beliefs. Unfortunately, most of Greco-Roman scientific research was included in the works that were destroyed or suppressed. The Academy School of Philosophy, which had roots going back to 387 BCE, finally closed its doors in 528 CE, after 916 years of considered thought (though with interruptions), its teachers chased away, hunted down as pagans. The new religion destroyed far more than it saved, but in all this chaos, a new world view evolved that was based on faith. This would change the mapmakers’ approach to representing the world – at least for a few hundred years.

Sebastian Munster (1448–1552) was a theologian and Hebrew scholar who taught at the University of Heidelberg. Like many learned people of his age, he also had an interest in geography and mapmaking. He produced two major works: the first, in 1540, was Ptolemy’s Geography with 48 woodcut maps. He carved the names of places, cities and states on removable blocks, which enabled the map to be changed and updated without recarving the entire map. His next cartographic work was Cosmography , published in 1544, in which he mapped each continent separately and listed the sources upon which his maps were compiled. Moreover, the blank spaces were ‘decorated’ with strange fictional races and creatures that featured on the maps of Solinus. These went on to be copied onto maps produced up until the 18th century.

The disinformation spread by the works of Solinus had already been compounded by ‘Christian geography’; one such work was written in the 500s by Cosmas Indicopleustes, who believed that all things – the nature of the universe, all living things and the form of the earth – could be found in the Holy Scriptures.

In his earlier life, Cosmas had been a successful merchant trading over much of the known world, around the cities of the Mediterranean and as far east as Ceylon (Sri Lanka). He converted to Christianity and eventually settled into the cloistered life of a monk, retiring to a monastery in the Sinai desert. He produced a work called Christian Topography , in which he looked only to the scriptures, describing the world as a flat parallelogram, with Jerusalem at its centre. It was written in Ezekiel 5.5: ‘I have set Jerusalem in the midst of the nations and countries that are round about her.’ Cosmas argued that in the far north of the inhabited world there was a great mountain around which the sun and moon revolved, creating night and day. Beyond the centre lay a great ocean, and beyond that were other lands where, before the biblical flood, people lived but that were now uninhabited and inaccessible. Beyond these empty lands arose the four walls of the sky meeting in the dome of heaven, the ceiling of the tabernacle. In his Christian Topography , Cosmas berates arrogant and sceptical scholars who:

attribute to the heavens a spherical figure and a circular motion, and by geometrical method and calculations applied to the heavenly bodies, as well as by the abuse of words and by worldly craft, endeavour to grasp the position and figure of the world by means of the solar and lunar eclipses, leading others into error, while they are in error themselves, in maintaining that such phenomena could not represent themselves if the figure was other than spherical.

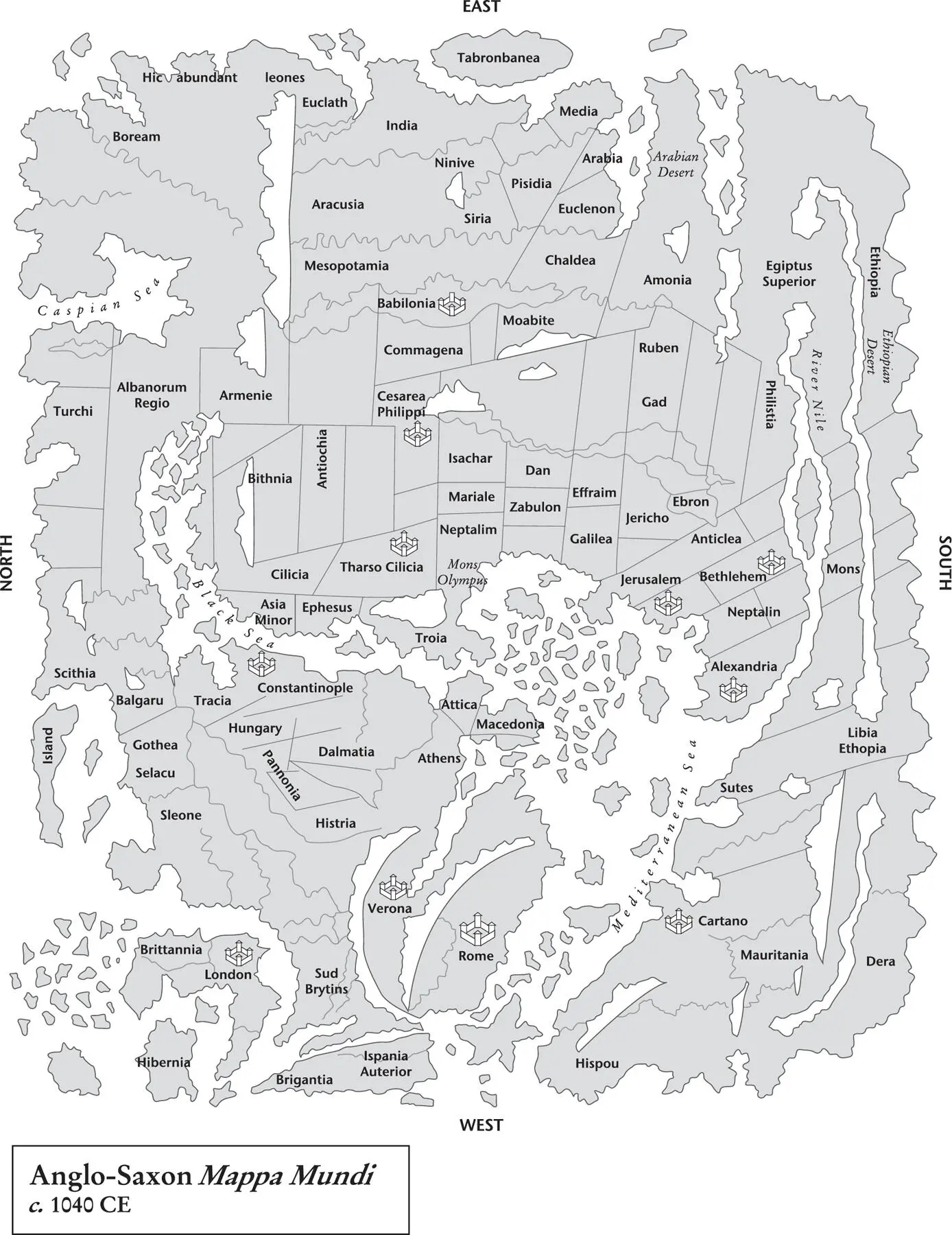

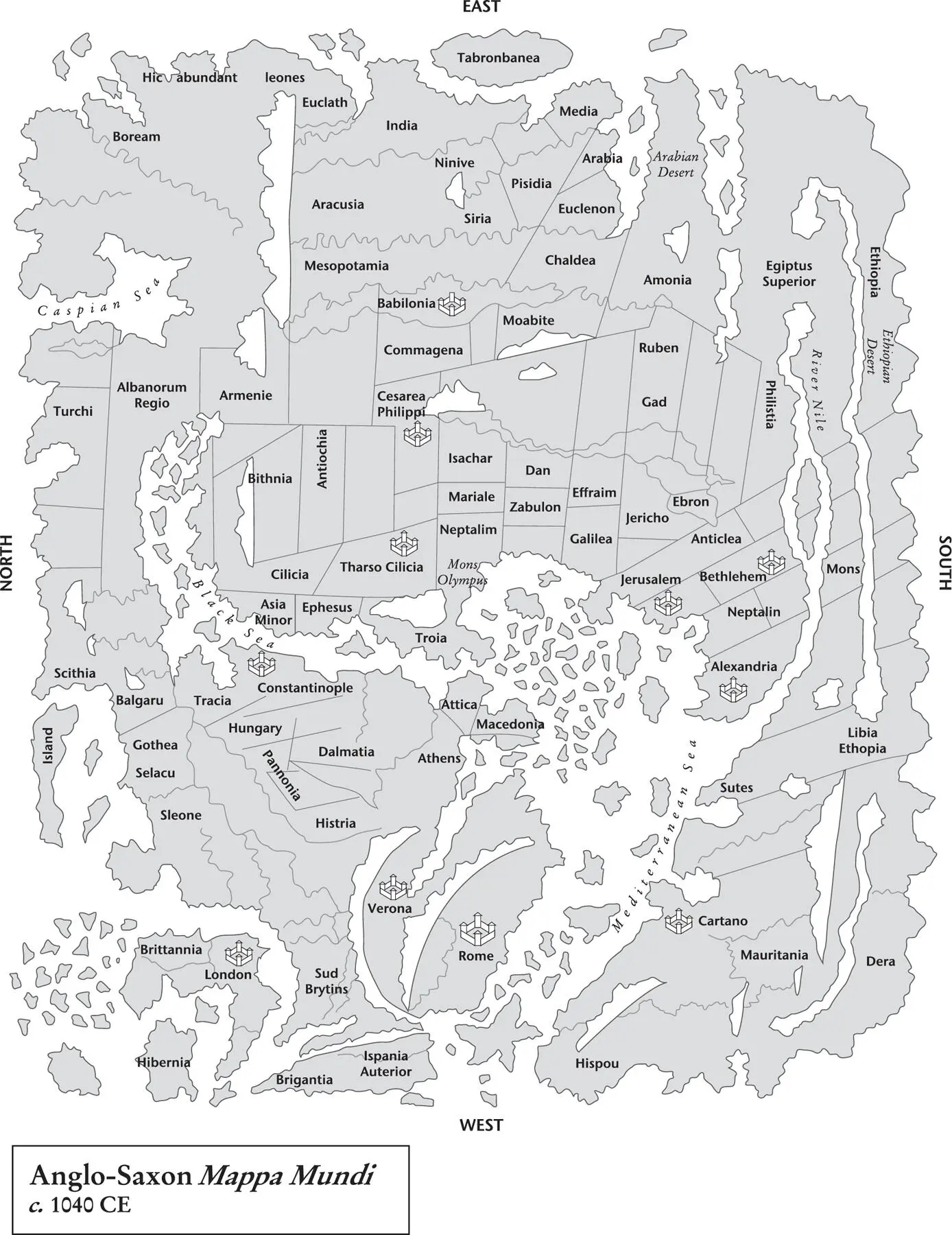

Map 10. The original of this map was created in around 1040 and contains the earliest-known vaguely realistic depiction of the British Isles.

Cosmas determinedly went on to discourage any consideration of Greek thought regarding the possibility of people inhabiting the Antipodean side of the spherical earth, for they ‘could not be of the race of Adam’. Did not the scriptures refer to the four corners of the earth? The Apostles were commanded to go out into the world and preach the Gospel to every creature; they could not reach the Antipodes and therefore such a place could not exist.

Now let’s take a look at the early medieval world as portrayed in Christian maps. I use the word ‘Christian’ very loosely, to describe a region and time, as in mapmaking cultures tended to overlap and influence each other. About 1,100 mappa mundi , or world maps, from this period are known to exist. The mappa mundi come in a number of groups, which include zonal maps, a group of diagrammatic maps that divide the world sphere into five climactic zones. Only two of these zones were believed to be inhabited: the northern temperate and the southern temperate, which were separated by an imaginary ocean along the equator.

Zonal maps attempted to fit landforms into the zonal concept, which emphasises the separating equatorial ocean and places north at the top, as we would view a world map today. They looked back to a Greek tradition where human existence was shaped by the natural world, and therefore it was believed that there was an unknown and inaccessible theoretical race occupying the southern temperate zone, which corresponded with the northern temperate zone. For the Christian mind this was an unresolved problem; this race was not mentioned in the Bible, so was it created by God?

Next (though in no particular order) are T-O (sometimes called the ‘Tripartite’) maps These offered a simplified description of geography, showing only the inhabited regions of the world as known to Roman and medieval scholars. The world map was illustrated within a circle, with the three land areas – Europe, Africa and Asia – divided by a T shape, representing water that reached out to a circular ocean. Most of these maps placed east ( oriens in Latin) at the top, giving us the term ‘orienting’. These maps also resolved the problem of an unknown race by completely ignoring the possibility, at least geographically. Isidore, Archbishop of Seville (580–636 CE), used this style of map in his epic Etymologiae (‘Origins’), a collection of works from antiquity that would probably have been lost without his efforts.

Читать дальше