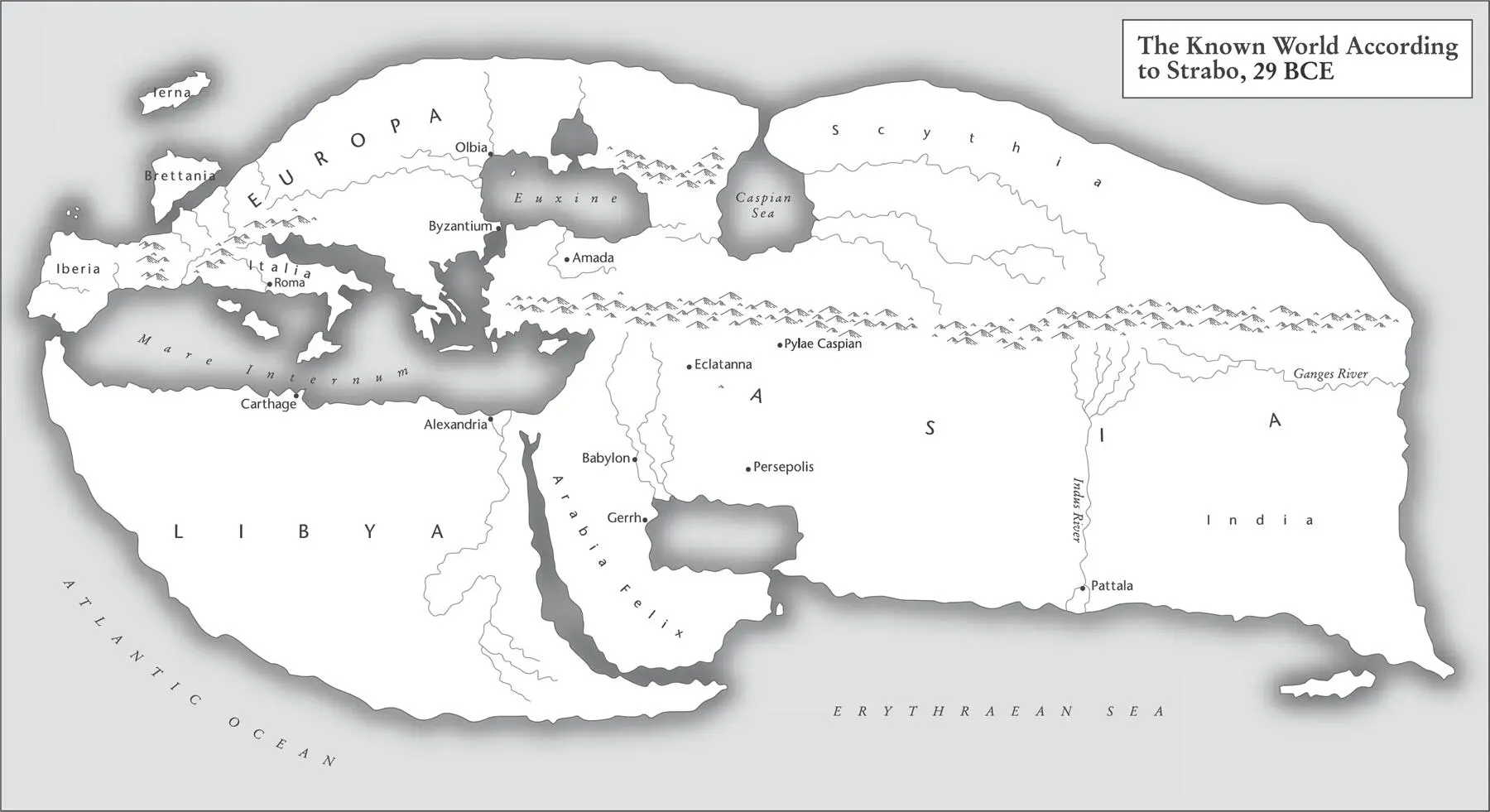

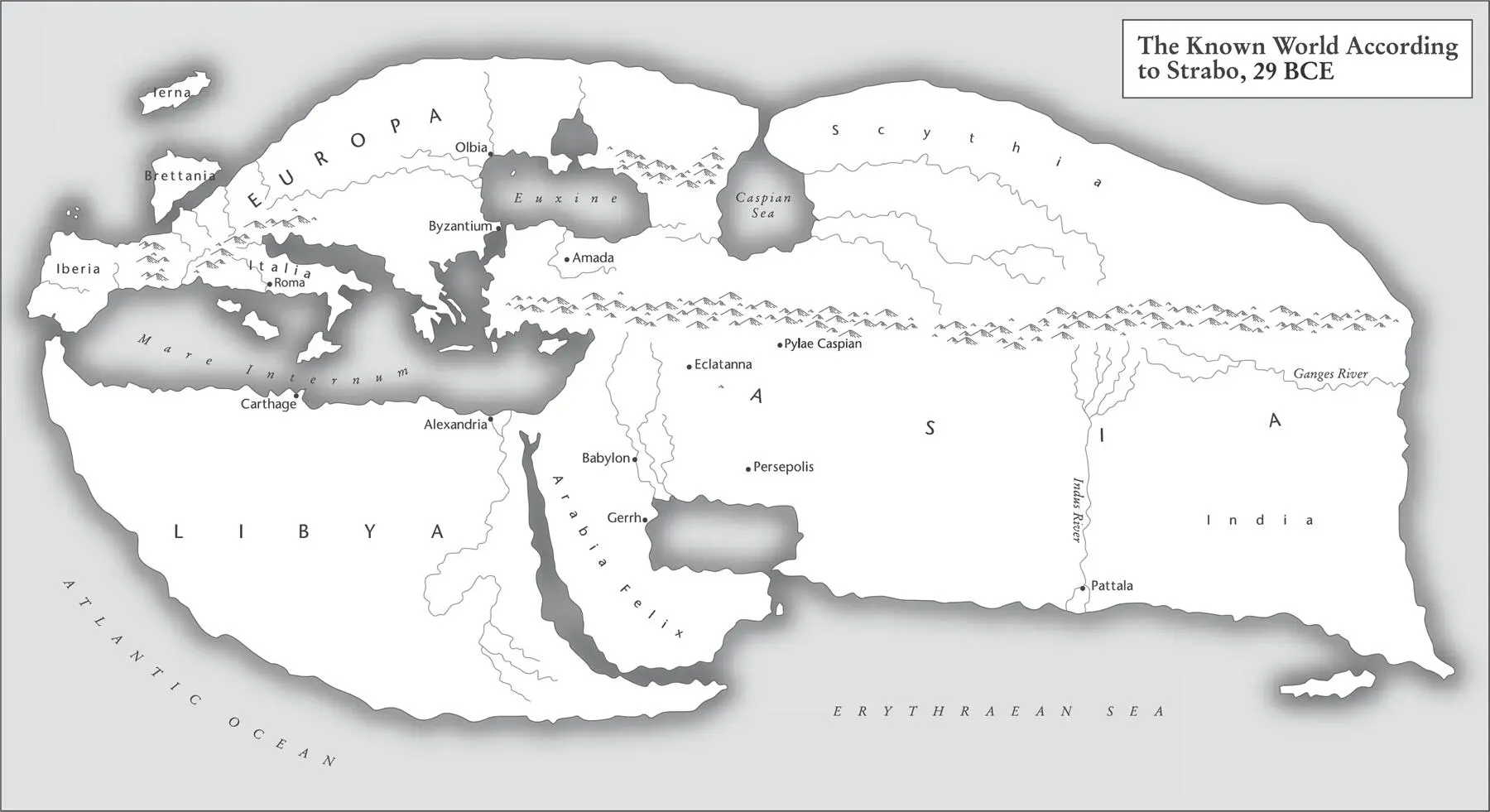

With such an education, contacts and considerable help from the bank of Mum and Dad, Strabo was able to travel and indulge his enquiring mind. He wrote his modestly titled Historical Notes , which in fact was a huge undertaking in 43 volumes that, alas, is now lost. However, his Geographica (‘Geography’), an encyclopaedia of geographical knowledge in 17 volumes, survives – that is, almost survives; part of the end of Volume Seven is lost.

During his time in Rome, Strabo witnessed the end of the Republic, a form of government that had existed for around 480 years. The change dated from 27 BCE when the Roman Senate granted extraordinary power to Gaius Octavius and Marcus Agrippa, great-nephews of the assassinated Julius Caesar (44 BCE). Gaius Octavius adopted the title Augustus and managed to bring peace and stability to what was now the Empire. By now Strabo had returned to Asia Minor, but he was back in Rome by 29 BCE to see the new emperor assume his full power.

Map 8. Strabo was pro-Roman by politics and Greek by culture. His concept of the world was influenced by Eratosthenes and other Greeks.

In 29 BCE Strabo travelled from Rome to Alexandria in Egypt in the company of his influential friend Aelius Gallus, Prefect of Egypt. Even travelling first class in a well-built galley, this would take around 21 days. Gallus toured his province of Egypt accompanied by Strabo, and part of his mission to the east was to take an expedition to Arabia, an area that was presumed, at least by the Romans, to be full of all kinds of treasures. The purpose of the expedition was to conclude a number of friendship treaties with the local peoples, which of course was intended to benefit Rome. However, the expedition was a failure; after some initial success, there followed a long march to the south through endless deserts, leading to a brief siege of Ma’rib, capital of the Kingdom of Saba. Meanwhile, the accompanying Roman fleet destroyed the port of Aden. All these efforts came to naught after Gallus lost the bulk of his army. Originally 10,000 strong, the weary, sun-scorched survivors retreated to Egypt. The emperor recalled Gallus back to Rome, in some disgrace, but Strabo stayed in Egypt and spent at least some time in the Great Library at Alexandria, the old haunt of Eratosthenes.

Strabo returned to Rome in around 20 BCE, now a Roman citizen, and there settled into writing. He began his surviving work, Geographica (‘Geography’), the first edition of which was published in 7 CE, far from Rome for some reason. The work was consequently unknown in Rome but widely read in the Romanised east, and maybe that was Strabo’s intention, his pro-Roman legacy. After a long gap, there was a second edition in 23 CE, but this was the last year of Strabo’s life. He was now back in his home town of Amaseia, and died aged 87, having achieved perhaps the first attempt to assemble the best available geographical knowledge into a single work, which would go on to influence the work of many others.

PTOLEMY

Claudius Ptolemy was probably born in Alexandria around 100 CE. Despite his family name, he was not related to the Egyptian royal family, the founders and protectors of the Great Library. It was in this city, some 400 years after its foundation, that Ptolemy created his masterwork, Geographite hyphegesis (‘Guide to Geography’), as it was later known among its readership.

The Great Library at Alexandria, dedicated to the Nine Muses of the Arts, had been destroyed some 148 years before Ptolemy’s birth during Caesar’s Civil War in 48 BCE, when his forces were threatened by the Egyptian navy. During attempts to destroy that threat, Caesar’s own ships were burnt and, according to some descriptions, the resulting conflagration spread to the Great Library, destroying much of its invaluable contents.

Ptolemy sat among the patched-up halls of the library compiling his Geography in around 150 CE. Much of his writing relied on earlier work, especially that of Marinus of Tyre (70–130 CE). His study was written in Greek – as were most of its precursors – on a papyrus roll over eight sections or ‘books’, and in it he reviewed the combined total research of the classical world to date. The outcome of this monumental work was to define mapmaking, at least in the West, for the next 2,000 years.

Ptolemy regarded himself firstly as a mathematician, astronomer and philosopher. He did not refer to himself as a geographer. Indeed, the Greek spoken by Ptolemy had no word for geography. What we call a map, he called a pinax , or he may have used the phrase periodos ges , a ‘circuit of the earth’. In time, these terms would be replaced by the Latin mappa .

Ptolemy had established his credentials, first in astronomy, writing a work called Ho megas astronomos (‘The Mathematical Collection’), later known as the Almagest (Arab astronomers used the Greek superlative term Megiste for this work, and when the definite article in Arabic, ‘ al ’, was prefixed it became Almagest ).

The Almagest ’s 13 books deal in detail with astronomical concepts, the stars, the solar system and other observable objects. In them, Ptolemy produced his geocentric theory that placed the earth at the centre of the universe, often known as the Ptolemaic Cosmology, and this view was held by the majority of observers and thinkers until the heliocentric, sun-centred theory developed by Copernicus 1,300 years later.

In the Almagest Ptolemy wrote:

I know that I am mortal by nature, and ephemeral; but when I trace at my pleasure the windings to and fro of the heavenly bodies, I no longer touch earth with my feet, I stand in the presence of Zeus himself and take my fill of ambrosia.

He obviously felt some passion for his work. Now we come to Ptolemy’s Geography . He approached this work by first gathering the learning from the Babylonian, Greek, Roman and Persian worlds and applying this accumulated knowledge into a mathematical framework.

A large part of Book 1 describes how to draw the maps using his ‘projection’ – his coordinates are in degrees: 360 to complete the circle, 60 minutes to a degree, just as we still use. His east–west longitudes are measured eastwards beginning with 0 degrees at a point just west of the Canary Islands, known to him as the ‘Blessed Isles’. The north–south latitudes are measured heading north from the equator, again like our own today. He did, however, mark his degree sign with an asterisk: 10*, not 10° as we now use.

His skill was in devising this mathematical formula that allows the rendering of the earth’s sphere onto a flat surface. This was an improvement on past ‘world’ map projections, given that all maps are some kind of compromise when rendering a sphere onto a flat sheet of papyrus or paper. He also placed north at the top, an orientation once again familiar today. This was the first example of a conical map projection. Ptolemy had succeeded in providing a simple, reliable method of drawing a world map.

The complete text drew on all the works available to Ptolemy in Alexandria, such as Tacitus with his descriptions of Gaul. Ptolemy laid down rules for mapping local features such as cities, harbours and farms. He stressed the importance of astronomy and mathematics to geography, creating a system based on the unchanging features of the sun and the stars, and demanding that longitude and latitude be used to fix locations of geographical features: mountains, estuaries, settlements, etc. By adhering to this system, mapmakers ensured their maps were accurate and could be systematically reproduced. That is, of course, as long as the information supplied was accurate – a problem the modern mapmaker still encounters.

Читать дальше