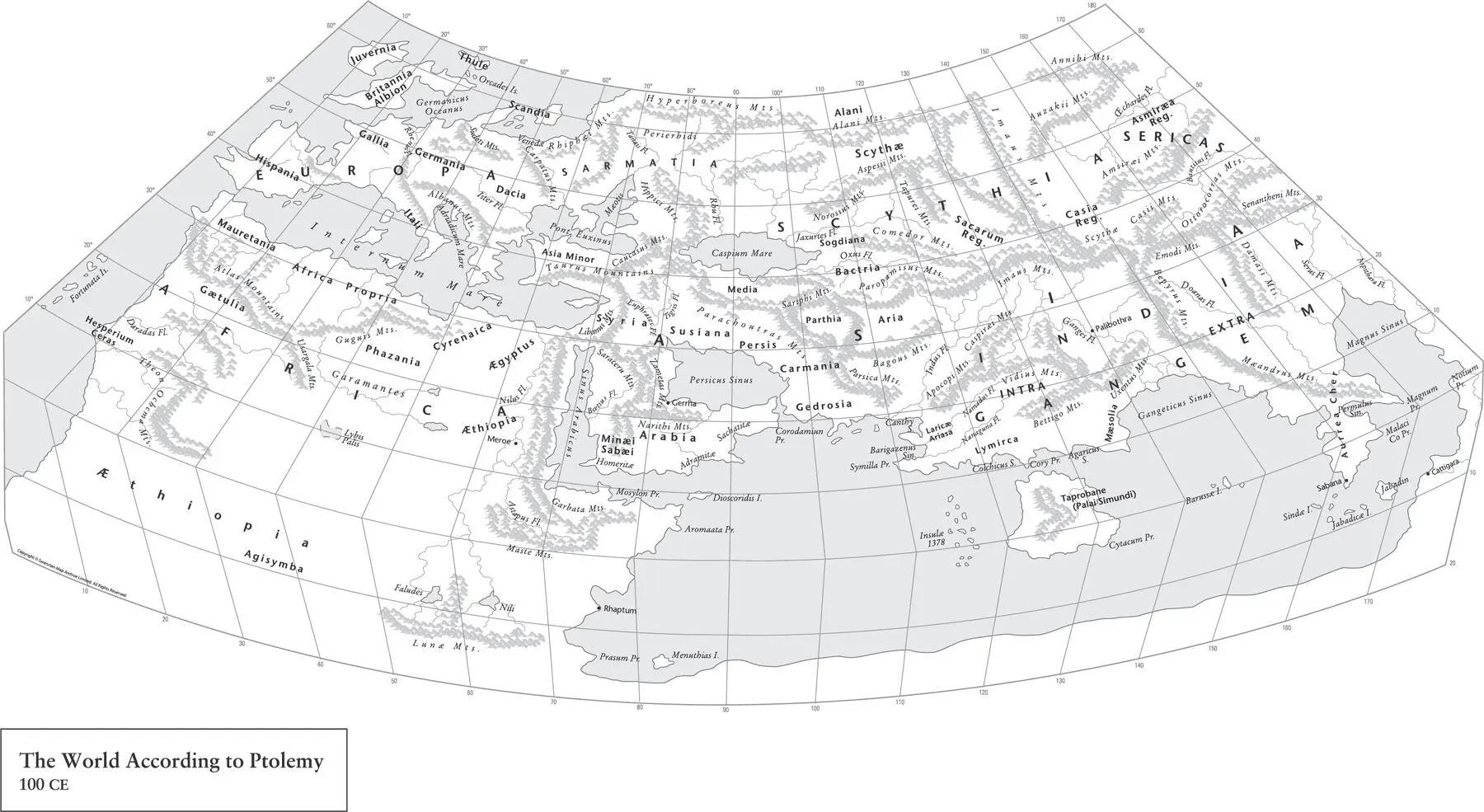

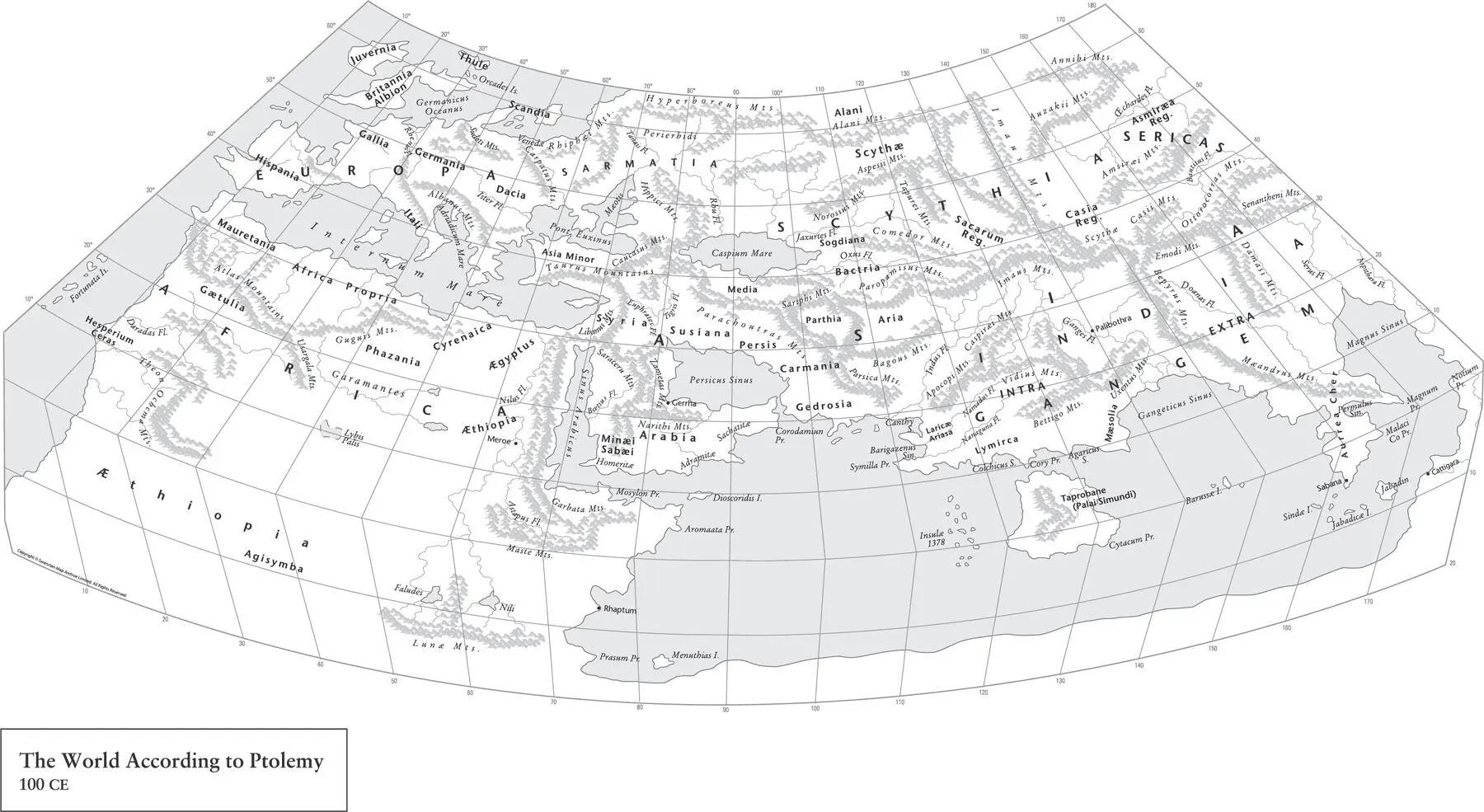

The completed text of Geography is more than a list of geographical coordinates. Ptolemy chose to review and carefully analyse the descriptions available to him, then selected the most reliable, but he still left a warning as to the reliability of some descriptions. The mapmaker is only as good as the information he has to hand. This gazetteer was eventually to list some 8,000 locations, according to their latitude and longitude, beginning in the west with the British Isles, moving eastwards across Europe towards Asia Minor and ending with India in the east, his known world. It is not known if Ptolemy produced maps himself to go with his geographic gazetteer; if he did, none have survived.

Ptolemy divided the globe’s circumference into 360 degrees (the Babylonian sexagismal system); every degree was measured in units of 60. He estimated each degree at 500 stades (2,700 kilometres), a total of 180,000 stades. He envisaged his world as smaller than Eratosthenes’ calculations; however, he did argue that the world’s inhabited regions were larger than many believed, reaching from the Fortunate Isles in the west to Cattiagara in the east, believed to be somewhere in modern north Vietnam. From north to south was measured at 40,000 stades from Thule at 63 degrees north to Agisymta in sub-Saharan Africa at 16 degrees south. Ptolemy’s world had blurred edges based on theories, stories and guesswork. For instance, he believed that a large, unknown continent existed in the southern hemisphere in order to balance Europe and Asia in the northern hemisphere and that the Indian Ocean was enclosed by Africa, extending eastwards to join up with Asia. This last feature appeared on Ptolemaic maps even after the Portuguese had sailed around Africa into the Indian Ocean.

After Ptolemy’s time, whatever was left of the Great Library of Alexandria was lost through invasion and war, a fact that haunts the enquiring mind to this day. However, some works survived and Geography was one of them. The earliest known copy of Geography that exists is in Arabic and dates from the 12th century, preserved by Islamic scholars who reintroduced it into Europe, where it was translated from Arabic into Byzantine Greek in the 13th century and then into Latin in the 15th century. The work made it into print in 1475. The Ulm edition, printed in 1482 in Germany, included woodcut maps of new discoveries like Greenland, which was placed using the Ptolemaic principles of its longitude and latitude. Now, 1,300 years after his death, Ptolemy was a bestseller as his books poured off the printing presses.

Map 9. Ptolemy’s maps were the first to use longitudinal and latitudinal lines as well as specifying terrestrial locations by celestial observations.

Ptolemy’s mathematical scientific system made the chaotic world understandable by the application of methodical geometric order. Thousands of descriptions made by sailors, travellers and generals, with all their sense of wonder at the almost endless diversity of landscapes and peoples, came together as an understandable whole. Ptolemy’s achievement lasted into and past the Renaissance. I still plot my maps in degrees and minutes. I still check gazetteers of verified locations – now online, of course.

These things belong to the loftiest and loveliest of intellectual pursuits, namely to exhibit to human understanding through mathematics both the heavens themselves in their physical nature (since they can be seen in their revolution about us), and the nature of the earth through a portrait (since the real earth, being enormous and not surrounding us, cannot be inspected by any one person either as a whole or part by part).

Ptolemy’s Geography , Book I

The classical world in which this achievement was created, though, was now under threat.

4 4. The Road to Paradise 5. Visions of a New World 6. Pre-Columbian Voyages in the Atlantic 7. The First Circumnavigation of the World 8. The English World View 9. Mercator Navigates the World 10. Terra Australis (‘South Land’) 11. Enslaved 12. The Cassinis’ Conceptions 13. The Problem with Empires 14. Gone West 15. A World at War 16. The Second Round 17. Cities 18. Another View of Earth Acknowledgements About the Publisher

THE ROAD TO PARADISE 4. The Road to Paradise 5. Visions of a New World 6. Pre-Columbian Voyages in the Atlantic 7. The First Circumnavigation of the World 8. The English World View 9. Mercator Navigates the World 10. Terra Australis (‘South Land’) 11. Enslaved 12. The Cassinis’ Conceptions 13. The Problem with Empires 14. Gone West 15. A World at War 16. The Second Round 17. Cities 18. Another View of Earth Acknowledgements About the Publisher

By the beginning of the 4th century CE, the empire in the West was perhaps less ‘Roman’: many of its provinces were in the ownership of federated tribes – semi-independent kingdoms concerned with their own politics. The Roman state was a less cohesive entity. In the East, Alexandria, still a centre of learning, though much reduced, also became a centre of revolt. The museum buildings, by now over 500 years old and not in the best of condition, were finally destroyed, though the Great Library building still survived. In 391 CE, the library finally met its end when a Christian mob broke in, burned the almost irreplaceable contents and turned the building into a church, a triumph of faith over reason.

Meanwhile, a few years earlier at the opposite end of the empire along Hadrian’s Wall in Britannia, Magnus Maximus, who was commander of Britain, withdrew troops from northern and western Britain in pursuit of his own ambitions for imperial rule, usurping power from Emperor Gratian. His attempts ultimately failed, being defeated by Emperor Theodosius, and Maximus was finally executed in 388. With his death, Britannia came back under the direct rule of Theodosius, that is until 392 when another usurper, Flavius Eugenius, made another bid for imperial power. Again, after just two years his short-lived rule over the West failed when Theodosius marched from Constantinople at the head of his army and defeated Eugenius at the Battle of Frigidus in September 394. Eugenius was captured and executed as a criminal. The following year, 395, the victorious Theodosius died, leaving his 10-year-old son Honorus as Emperor in the West. However, the real power in the West was in the hands of Flavius Stilicho, a highly experienced general who had risen through the ranks. In 402 it was his decision to finally strip Hadrian’s Wall of its remaining garrison, and possibly other troops in Britain, to face wars with the Ostrogoths and Visigoths on the Continent.

Meanwhile, the Romano-Britons now dispensed with imperial authority. In 407, they selected Flavius Claudius Constantinus, or Constantine III, as their leader, who now declared himself the Western Roman Emperor, gathered the last Roman troops in Britain and headed for Gaul. Sixty-six years later, in the West, Rome was gone, replaced by a collection of ‘Barbarian’ kingdoms. The new kingdoms lived among the remains of a once great empire. The skills needed to repair and maintain roads, bridges, aqueducts and great buildings were lost. The Anglo-Saxon poem The Ruin , written by an unknown author, looks upon the moss-covered buildings with a sense of wonder:

Wondrous is this wall-stead, wasted by fate.

Battlements broken, giant’s work shattered.

Roofs are in ruin, towers destroyed,

broken the barred gate, rime on the plaster,

walls gape, torn up, destroyed,

Читать дальше