It is tempting to think of ectotherms as ‘primitive’ and endotherms as having gained ‘advanced’ control over their environment, but it is difficult to justify this view. Most environments on earth are inhabited by mixed communities of endothermic and ectothermic animals. This includes some of the hottest – e.g. desert rodents and lizards – and some of the coldest – penguins and whales together with fish and krill at the edge of the Antarctic ice sheet. Rather, the contrast is between the high cost–high benefit strategy of endotherms and the low cost–low benefit strategy of ectotherms. But their coexistence tells us that both strategies, in their own ways, can ‘work’.

2.3.4 Life at low temperatures

The greater part of our planet is below 5°C. More than 70% of the planet is covered with seawater: mostly deep ocean with a remarkably constant temperature of about 2°C. If we include the polar ice caps, more than 80% of earth’s biosphere is permanently cold.

chilling injury

By definition, all temperatures below the optimum have adverse effects, but there is usually a wide range of such temperatures that cause no physical damage and over which any effects are fully reversible. There are, however, two quite distinct types of damage at low temperatures that can be lethal, either to tissues or to whole organisms: chilling and freezing. Many organisms, particularly tropical and subtropical plants, are damaged by exposure to temperatures that are low but above freezing point – so‐called ‘chilling injury’. The fruits of the banana blacken and rot after exposure to chilling temperatures and many rainforest species are sensitive to chilling. Many insects also succumb to the effects of chilling at temperatures well above the freezing point of their body fluids. In these chill‐sensitive insects, including the majority of temperate, subtropical and tropical species, chilling causes a loss of homeostasis that leads to paralysis, injury and ultimately death (Bale, 2002).

temperatures below 0°C

Temperatures below 0°C can have lethal physical and chemical consequences even though ice may not be formed. Water may ‘supercool’ to temperatures at least as low as −40°C, remaining in an unstable liquid form in which its physical properties change in ways that are certain to be biologically significant: its viscosity increases, its diffusion rate decreases and its degree of ionisation decreases. In fact, ice seldom forms in an organism until the temperature has fallen several degrees below 0°C. Body fluids remain in a supercooled state until ice forms suddenly around particles that act as nuclei. The concentration of solutes in the remaining liquid phase rises as a consequence. It is rare for ice to form within cells and it is then inevitably lethal, but the freezing of extracellular water is one of the factors that prevents ice forming within the cells themselves (Wharton, 2002), since water is withdrawn from the cell, and solutes in the cytoplasm (and vacuoles) become more concentrated. The effects of freezing are therefore mainly osmoregulatory: the water balance of the cells is upset and cell membranes are destabilised. The effects are essentially similar to those of drought and salinity.

frost resistance of plants and their parts

Plants inhabiting high latitudes and altitudes are particularly exposed to frost damage. Woody alpine plants, for example, can experience frost damage at any time of year (Neuner, 2014). In summer, the most frost‐susceptible organs are reproductive shoots (−4.6°C), followed by immature leaves (−5.0°C), fully expanded leaves (−6.6°C), vegetative buds (−7.3°C) and xylem tissue (−10.8°C). These levels of resistance can be insufficient to survive frost events in summer and it may be that the most frost‐susceptible parts define the upper limit of elevation for the distribution of such woody species. The same plant tissues are much less sensitive to frost damage in winter, the reproductive buds being most susceptible (−23.4°C), but with greater levels of freezing resistance in vegetative buds (−30 to −50°C), leaves (−25 to −58.5°C) and stems (−30 to −70°C). Mechanisms of frost resistance include the production of cryoprotectant proteins, which appear to protect membranes and proteins against the severe dehydration stress associated with freezing, and the rapid accumulation of soluble carbohydrates, including sucrose, that serve to reduce cellular dehydration during freezing (Wisniewski et al ., 2014).

metabolic strategies of cold hardiness

Insects, and other taxa, have two main metabolic strategies that allow survival through the low temperatures of winter. A ‘freeze‐avoiding’ strategy uses the synthesis of antifreeze proteins and the accumulation of extremely high levels of carbohydrate cryoprotectants (most often glycerol) so that body fluids can supercool to temperatures well below those normally encountered. A contrasting ‘freeze‐tolerant’ strategy involves the regulated freezing of up to about 65% of total body water in extracellular spaces. Ice formation outside the cells is often triggered by the action of specific ice‐nucleating agents or proteins, whereas low molecular weight cryoprotectants are used to maintain a liquid intracellular space and to protect membrane structure. Storey and Storey (2012) list two further strategies discovered more recently. The first, described for soil‐dwelling invertebrates and particularly polar species, is ‘cryoprotective dehydration’, which combines extreme dehydration, in which virtually all freezable water is lost, together with high cryoprotectant levels that stabilise macromolecules. And more recently still, Sformo et al . (2010), in a study of the Alaskan bark beetle ( Cucujus clavipes ), showed that larvae at lower temperatures did not freeze but transitioned into a vitrified state (a non‐crystalline amorphous solid) in which they could survive down to –100°C. The ‘vitrification’ strategy is accompanied by extensive dehydration and accumulation of antifreeze proteins and high concentrations of polyols.

acclimation and acclimatisation

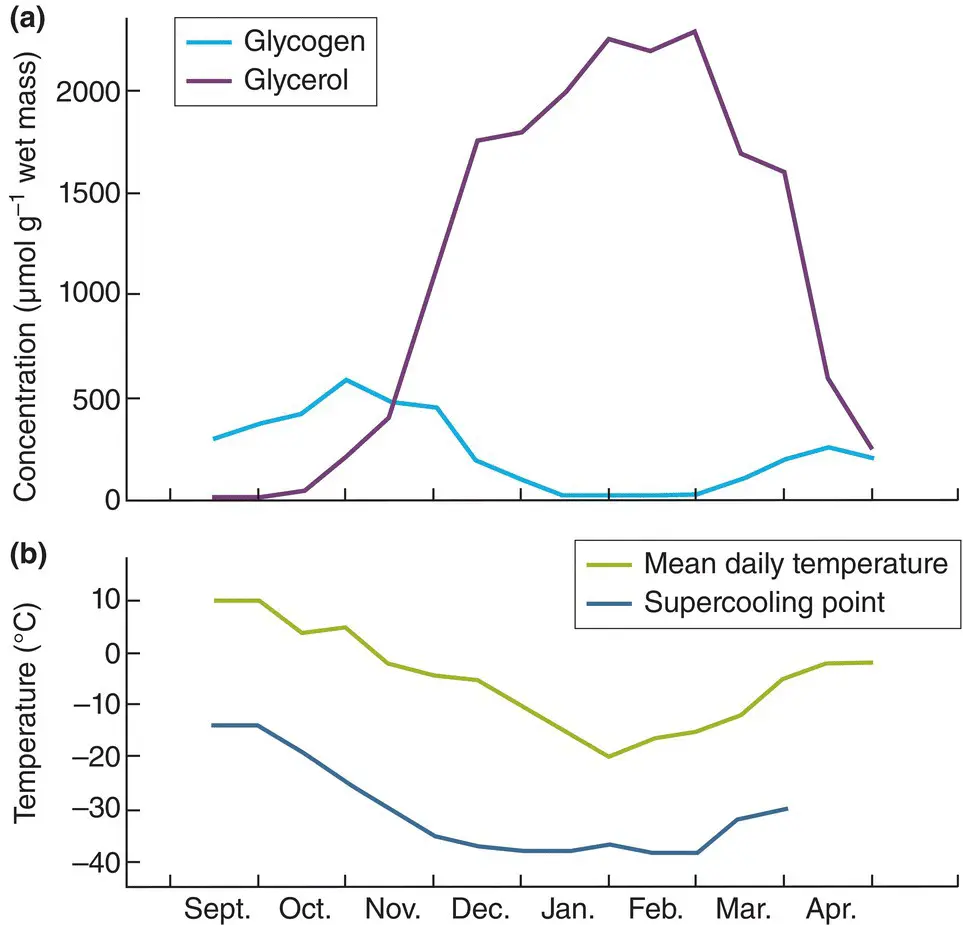

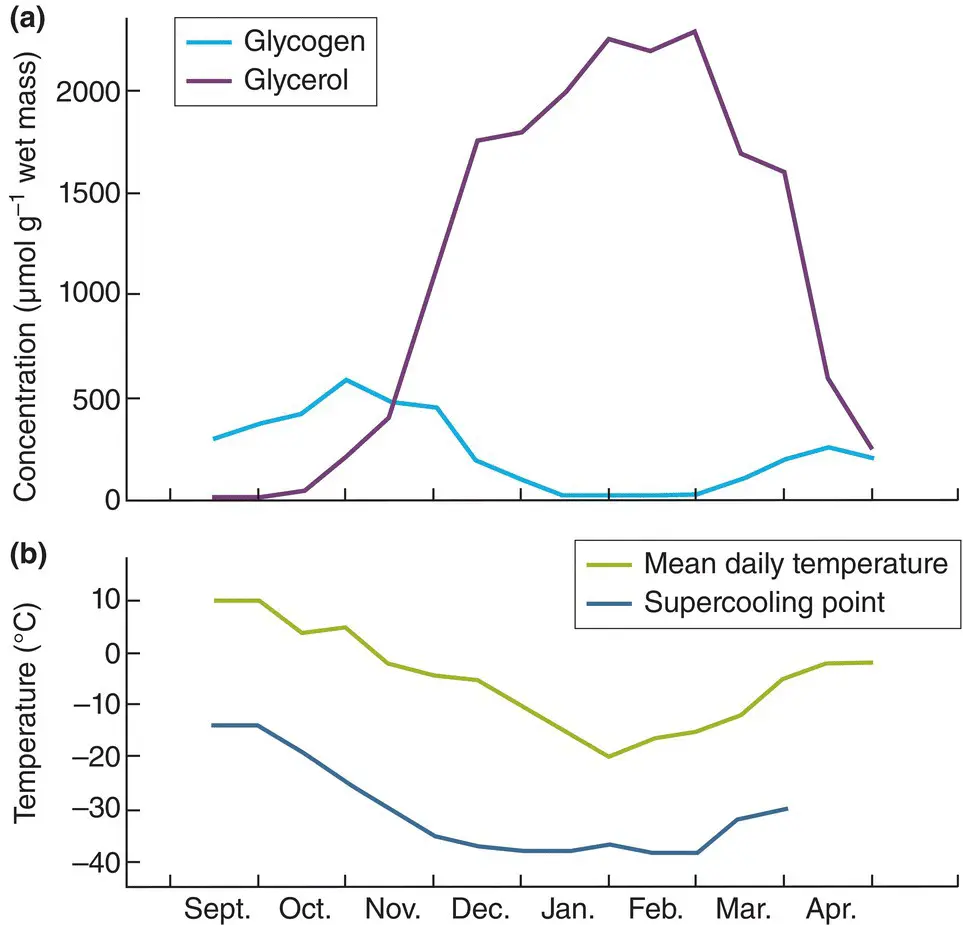

The tolerances of organisms to low temperatures are not fixed but are preconditioned by the experience of temperatures in their recent past. This process is called acclimation when it occurs in the laboratory and acclimatisation when it occurs naturally. Acclimatisation may start as the weather becomes colder in the autumn, stimulating the conversion of almost the entire glycogen reserve of animals into polyols such as glycerol ( Figure 2.13), but this can be an energetically costly affair: about 16% of the carbohydrate reserve may be consumed in the conversion of the glycogen reserves.

Figure 2.13 Acclimatisation involves conversion of glycogen to glycerol in a caterpillar.(a) As a result of cooling autumn temperatures, larvae of the goldenrod gall moth, Epiblema scudderiana , convert their stores of glycogen to glycerol, which eventually constitutes over 19% of the caterpillar’s body mass. (b) The high levels of glycerol plus antifreeze proteins suppress the larval supercooling point from –14°C in late summer to –38°C by mid‐winter, values well below environmental temperature extremes.

Source : (a, b) From Storey & Storey (2012), after Rickards et al . (1987).

Acclimatisation aside, individuals commonly vary in their temperature response depending on the stage of development they have reached. Probably the most extreme form of this is when an organism has a dormant stage in its life cycle. Dormant stages are typically dehydrated, metabolically slow and tolerant of extremes of temperature.

Читать дальше