5.6.1 Common hash functions

The hash functions most commonly used through the 1990s and 2000s evolved as variants of a block cipher with a 512 bit key and a block size increasing from 128 to 512 bits. The first two were designed by Ron Rivest and the others by the NSA:

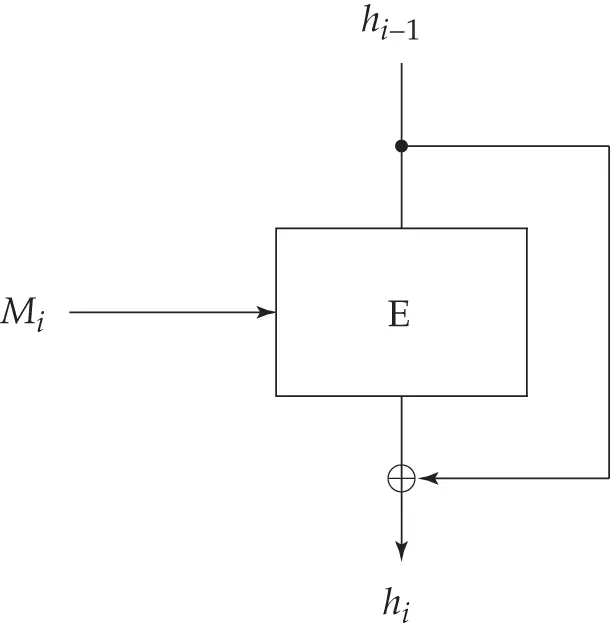

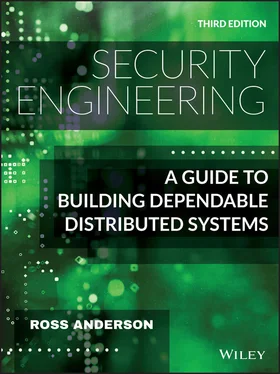

Figure 5.16 : Feedforward mode (hash function)

MD4 has three rounds and a 128 bit hash value, and a collision was found for it in 1998 [568];

MD5 has four rounds and a 128 bit hash value, and a collision was found for it in 2004 [1983, 1985];

SHA-1, released in 1995, has five rounds and a 160 bit hash value. A collision was found in 2017 [1831], and a more powerful version of the attack in 2020 [1148];

SHA-2, which replaced it in 2002, comes in 256-bit and 512-bit versions (called SHA256 and SHA512) plus a number of variants.

The block ciphers underlying these hash functions are similar: their round function is a complicated mixture of the register operations available on 32 bit processors [1670]. Cryptanalysis has advanced steadily. MD4 was broken by Hans Dobbertin in 1998 [568]; MD5 was broken by Xiaoyun Wang and her colleagues in 2004 [1983, 1985]; collisions can now be found easily, even between strings containing meaningful text and adhering to message formats such as those used for digital certificates. Wang seriously dented SHA-1 the following year in work with Yiqun Lisa Yin and Hongbo Yu, providing an algorithm to find collisions in only  steps [1984]; it now takes about

steps [1984]; it now takes about  computations. In February 2017, scientists from Amsterdam and Google published just such a collision, to prove the point and help persuade people to move to stronger hash functions such as SHA-2 [1831] (and from earlier versions of TLS to TLS 1.3). In 2020, Gaëtan Leurent and Thomas Peyrin developed an improved attack that computes chosen-prefix collisions, enabling certificate forgery at a cost of several tens of thousands of dollars [1148].

computations. In February 2017, scientists from Amsterdam and Google published just such a collision, to prove the point and help persuade people to move to stronger hash functions such as SHA-2 [1831] (and from earlier versions of TLS to TLS 1.3). In 2020, Gaëtan Leurent and Thomas Peyrin developed an improved attack that computes chosen-prefix collisions, enabling certificate forgery at a cost of several tens of thousands of dollars [1148].

In 2007, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) organised a competition to find a replacement hash function family [1411]. The winner, Keccak, has a quite different internal structure, and was standardised as SHA-3 in 2015. So we now have a choice of SHA-2 and SHA-3 as standard hash functions.

A lot of deployed systems still use hash functions such as MD5 for which there's an easy collision-search algorithm. Whether a collision will break any given application can be a complex question. I already mentioned forensic systems, which keep hashes of files on seized computers, to reassure the court that the police didn't tamper with the evidence; a hash collision would merely signal that someone had been trying to tamper, whether the police or the defendant, and trigger a more careful investigation. If bank systems actually took a message composed by a customer saying ‘Pay  the sum

the sum  ’, hashed it and signed it, then a crook could find two messages ‘Pay

’, hashed it and signed it, then a crook could find two messages ‘Pay  the sum

the sum  ’ and ‘Pay

’ and ‘Pay  the sum

the sum  ’ that hashed to the same value, get one signed, and swap it for the other. But bank systems don't work like that. They typically use MACs rather than digital signatures on actual transactions, and logs are kept by all the parties to a transaction, so it's not easy to sneak in one of a colliding pair. And in both cases you'd probably have to find a preimage of an existing hash value, which is a much harder cryptanalytic task than finding a collision.

’ that hashed to the same value, get one signed, and swap it for the other. But bank systems don't work like that. They typically use MACs rather than digital signatures on actual transactions, and logs are kept by all the parties to a transaction, so it's not easy to sneak in one of a colliding pair. And in both cases you'd probably have to find a preimage of an existing hash value, which is a much harder cryptanalytic task than finding a collision.

5.6.2 Hash function applications – HMAC, commitments and updating

But even though there may be few applications where a collision-finding algorithm could let a bad guy steal real money today, the existence of a vulnerability can still undermine a system's value. Some people doing forensic work continue to use MD5, as they've used it for years, and its collisions don't give useful attacks. This is probably a mistake. In 2005, a motorist accused of speeding in Sydney, Australia was acquitted after the New South Wales Roads and Traffic Authority failed to find an expert to testify that MD5 was secure in this application. The judge was “not satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the photograph [had] not been altered since it was taken” and acquitted the motorist; his strange ruling was upheld on appeal the following year [1434]. So even if a vulnerability doesn't present an engineering threat, it can still present a certificational threat.

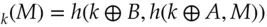

Hash functions have many other uses. One of them is to compute MACs. A naïve method would be to hash the message with a key: MAC  . However the accepted way of doing this, called HMAC, uses an extra step in which the result of this computation is hashed again. The two hashing operations are done using variants of the key, derived by exclusive-or'ing them with two different constants. Thus HMAC

. However the accepted way of doing this, called HMAC, uses an extra step in which the result of this computation is hashed again. The two hashing operations are done using variants of the key, derived by exclusive-or'ing them with two different constants. Thus HMAC  .

.  is constructed by repeating the byte

is constructed by repeating the byte 0x36as often as necessary, and  similarly from the byte

similarly from the byte 0x5C. If a hash function is on the weak side, this construction can make exploitable collisions harder to find [1091]. HMAC is now FIPS 198-1.

Another use of hash functions is to make commitments that are to be revealed later. For example, I might wish to timestamp a digital document in order to establish intellectual priority, but not reveal the contents yet. In that case, I can publish a hash of the document, or send it to a commercial timestamping service, or have it mined into the Bitcoin blockchain. Later, when I reveal the document, the timestamp on its hash establishes that I had written it by then. Again, an algorithm that generates colliding pairs doesn't break this, as you have to have the pair to hand when you do the timestamp.

Merkle trees hash a large number of inputs to a single hash output. The inputs are hashed to values that form the leaves of a tree; each non-leaf node contains the hash of all the hashes at its child nodes, so the hash at the root is a hash of all the values at the leaves. This is a fast way to hash a large data structure; it's used in code signing, where you may not want to wait for all of an application's files to have their signatures checked before you open it. It's also widely used in blockchain applications; in fact, a blockchain is just a Merkle tree. It was invented by Ralph Merkle, who first proposed it to calculate a short hash of a large file of public keys [1298], particularly for systems where public keys are used only once. For example, a Lamport digital signature can be constructed from a hash function: you create a private key of 512 random 256-bit values  and publish the verification key

and publish the verification key  as their Merkle tree hash. Then to sign

as their Merkle tree hash. Then to sign  SHA256(

SHA256(  ) you would reveal

) you would reveal  if the

if the  -th bit of

-th bit of  is zero, and otherwise reveal

is zero, and otherwise reveal  . This is secure if the hash function is, but has the drawback that each key can be used only once. Merkle saw that you could generate a series of private keys by encrypting a counter with a master secret key, and then use a tree to hash the resulting public keys. However, for most purposes, people use signature algorithms based on number theory, which I'll describe in the next section.

. This is secure if the hash function is, but has the drawback that each key can be used only once. Merkle saw that you could generate a series of private keys by encrypting a counter with a master secret key, and then use a tree to hash the resulting public keys. However, for most purposes, people use signature algorithms based on number theory, which I'll describe in the next section.

Читать дальше

steps [1984]; it now takes about

steps [1984]; it now takes about  computations. In February 2017, scientists from Amsterdam and Google published just such a collision, to prove the point and help persuade people to move to stronger hash functions such as SHA-2 [1831] (and from earlier versions of TLS to TLS 1.3). In 2020, Gaëtan Leurent and Thomas Peyrin developed an improved attack that computes chosen-prefix collisions, enabling certificate forgery at a cost of several tens of thousands of dollars [1148].

computations. In February 2017, scientists from Amsterdam and Google published just such a collision, to prove the point and help persuade people to move to stronger hash functions such as SHA-2 [1831] (and from earlier versions of TLS to TLS 1.3). In 2020, Gaëtan Leurent and Thomas Peyrin developed an improved attack that computes chosen-prefix collisions, enabling certificate forgery at a cost of several tens of thousands of dollars [1148]. the sum

the sum  ’, hashed it and signed it, then a crook could find two messages ‘Pay

’, hashed it and signed it, then a crook could find two messages ‘Pay  the sum

the sum  ’ and ‘Pay

’ and ‘Pay  the sum

the sum  ’ that hashed to the same value, get one signed, and swap it for the other. But bank systems don't work like that. They typically use MACs rather than digital signatures on actual transactions, and logs are kept by all the parties to a transaction, so it's not easy to sneak in one of a colliding pair. And in both cases you'd probably have to find a preimage of an existing hash value, which is a much harder cryptanalytic task than finding a collision.

’ that hashed to the same value, get one signed, and swap it for the other. But bank systems don't work like that. They typically use MACs rather than digital signatures on actual transactions, and logs are kept by all the parties to a transaction, so it's not easy to sneak in one of a colliding pair. And in both cases you'd probably have to find a preimage of an existing hash value, which is a much harder cryptanalytic task than finding a collision. . However the accepted way of doing this, called HMAC, uses an extra step in which the result of this computation is hashed again. The two hashing operations are done using variants of the key, derived by exclusive-or'ing them with two different constants. Thus HMAC

. However the accepted way of doing this, called HMAC, uses an extra step in which the result of this computation is hashed again. The two hashing operations are done using variants of the key, derived by exclusive-or'ing them with two different constants. Thus HMAC  .

.  is constructed by repeating the byte

is constructed by repeating the byte  similarly from the byte

similarly from the byte  and publish the verification key

and publish the verification key  as their Merkle tree hash. Then to sign

as their Merkle tree hash. Then to sign  SHA256(

SHA256(  ) you would reveal

) you would reveal  if the

if the  -th bit of

-th bit of  is zero, and otherwise reveal

is zero, and otherwise reveal  . This is secure if the hash function is, but has the drawback that each key can be used only once. Merkle saw that you could generate a series of private keys by encrypting a counter with a master secret key, and then use a tree to hash the resulting public keys. However, for most purposes, people use signature algorithms based on number theory, which I'll describe in the next section.

. This is secure if the hash function is, but has the drawback that each key can be used only once. Merkle saw that you could generate a series of private keys by encrypting a counter with a master secret key, and then use a tree to hash the resulting public keys. However, for most purposes, people use signature algorithms based on number theory, which I'll describe in the next section.