Some children have been observed to go through a “word spurt” period that has been found to begin when they are about 18 months old and which lasts for a few months (e.g. Clark 1993). During this period, new words spring up in the child's vocabulary on an almost daily basis. Some researchers (Goldfield and Reznick 1990) suggest only some children show a spurt while others show a linear pattern of vocabulary growth. One proposed explanation for the word spurt is “fast mapping,” i.e. that children are able to remember a word after very limited exposure to that word.

Another important stage occurs when children begin to link together more than two words, and enter what has been termed the “telegraphic stage.” At this point, children may produce strings of two‐, three‐, and even four‐word long units, sometimes more. The label “telegraphic” is used to reflect the fact that these strings tend to omit function words, such as articles, conjunctions, and prepositions, and largely consist of content words, such as nouns and verbs. For example, one child beginning to grow beyond the two‐word stage was heard to say “Baby Allison comb hair.”

Various methods have been used historically as well as currently to examine L1 speech. For example, Charles Darwin, the nineteenth‐century naturalist best known for his theory of evolution, made detailed diary recordings describing one of his sons' L1 acquisition. More recently, researchers have developed a system to measure early linguistic development by calculating the average number of morphemes, the meaning‐bearing units of language (words, such as “dog” and also prepositions like “to” and “at” and grammatical markers like “–ed” for past and a final “s” for plural in English), per utterance, i.e. the mean length of utterance(MLU). Roger Brown, a psychologist at Harvard University with a strong interest in language development, carried out a landmark longitudinal study (1973) with three young children (known by the pseudonyms Adam, Eve, and Sarah) between the ages of 20 and 36 months old, and found that while each child went through similar stages, and tended to acquire forms in a similar order, each child had her or his own unique rate of development, as calculated in terms of MLU (see Figure 2.2).

morphemes

Smallest meaning‐bearing unit of language (e.g. word units, like “dog,” and grammatical inflections, like the plural “–s”).

mean length of utterance (MLU)

Measurement used to calculate the development of children's grammar; number of morphemes divided by number of total utterances.

Figure 2.2 Development of MLU in three children (Brown, 1973) and children in a study by Miller and Chapman (1981).

Source: Berko Gleason, J. and Bernstein Ratner, N. (2017).

Table 2.2 Order of acquisition of English morphemes.

Source: Based on Brown, R. (1973).

| –ing |

| in, on |

| plural –s |

| possessive –s |

| the, a |

| past tense –ed |

| 3rd person singular –s |

| auxiliary “be” |

Brown found that the children acquired grammatical units, i.e. morphemes such as the plural “–s,” the past tense regular “–ed” ending, and the ending marking the progressive aspect (“–ing”), in a strikingly similar order, although not at the same rate (see Table 2.2). He also found that frequency of the forms in the input, the language of the children's environment, did not appear to affect their order of acquisition.

input

The language to which an individual is exposed in the environment.

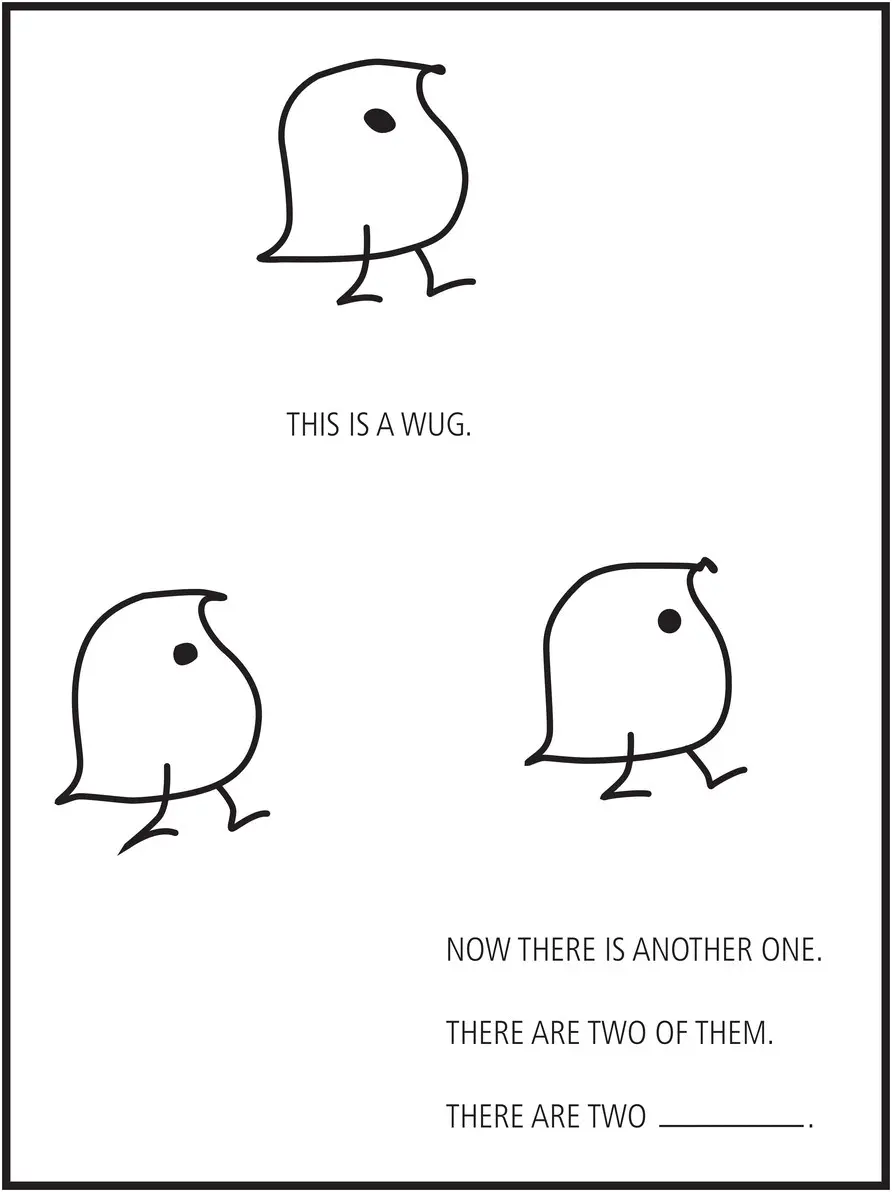

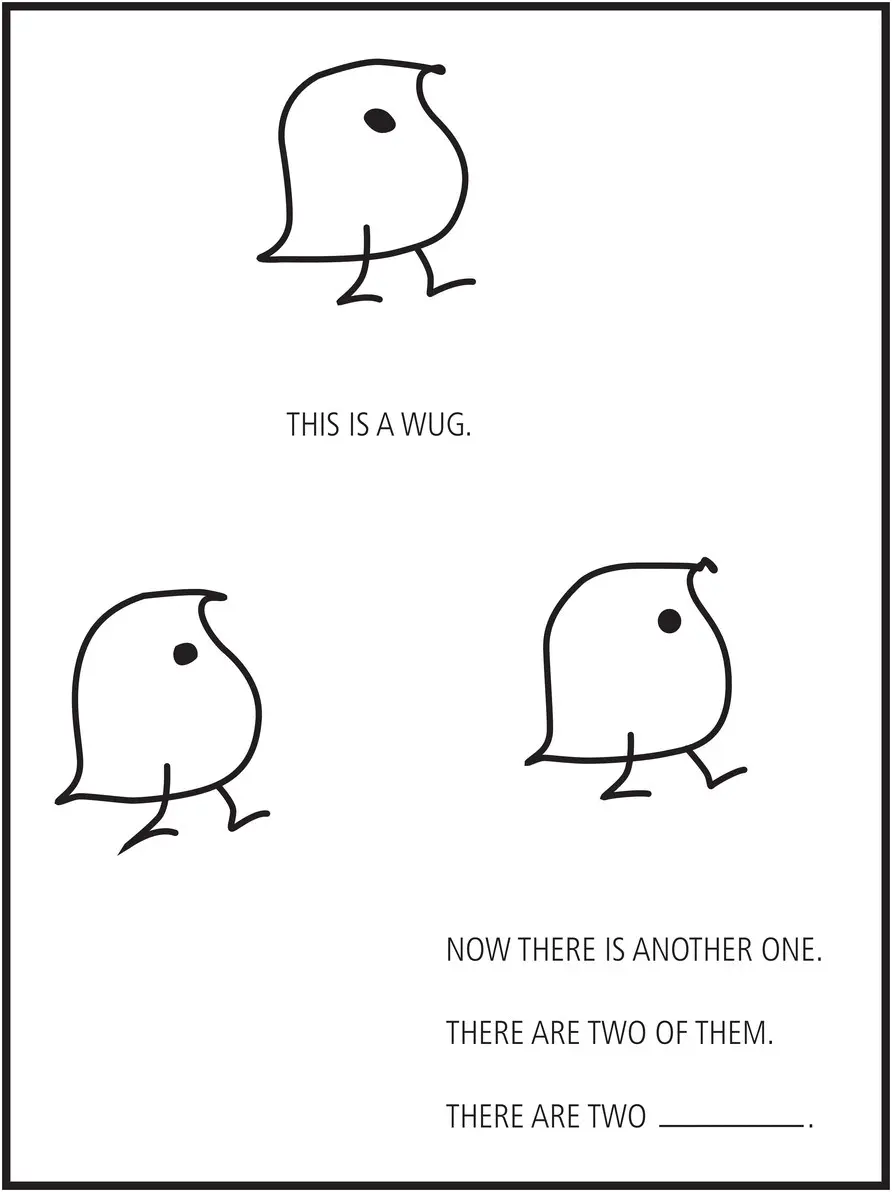

Other studies have found important evidence that children are able to generalize rules to items they have never been exposed to. As part of a simple, yet ingenious experiment, Jean Berko devised the “Wug” test (Berko 1958), in which nonsense words were presented to children along with their images (see Figure 2.3), and children were asked to pluralize the novel item, such as saying “wugs” for the nonsense word “wug.” In Berko's study, as many as 76% of four‐ to five‐year‐olds got the correct plural ending (wug – wugs, heaf – heafs) and an almost universal 97% of five‐ to seven‐year‐olds provided the correct form. The test also revealed that children are similarly able to provide the correct past tense “–ed” suffix to novel items (e.g. rick becomes ricked ). Such results reveal that children are able to apply underlying rules to new exemplars. The Wug test reveals that children are able to do more than simply produce a rote imitation of utterances they have been exposed to in the environment.

Figure 2.3 Berko's (1958) Wug test.

Source: Berko, J. (1958). © 1958, Taylor & Francis.

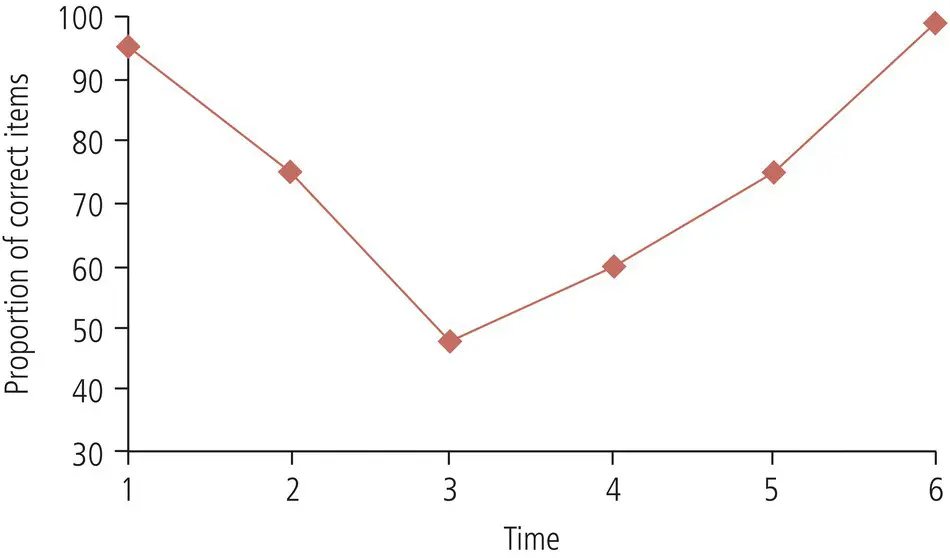

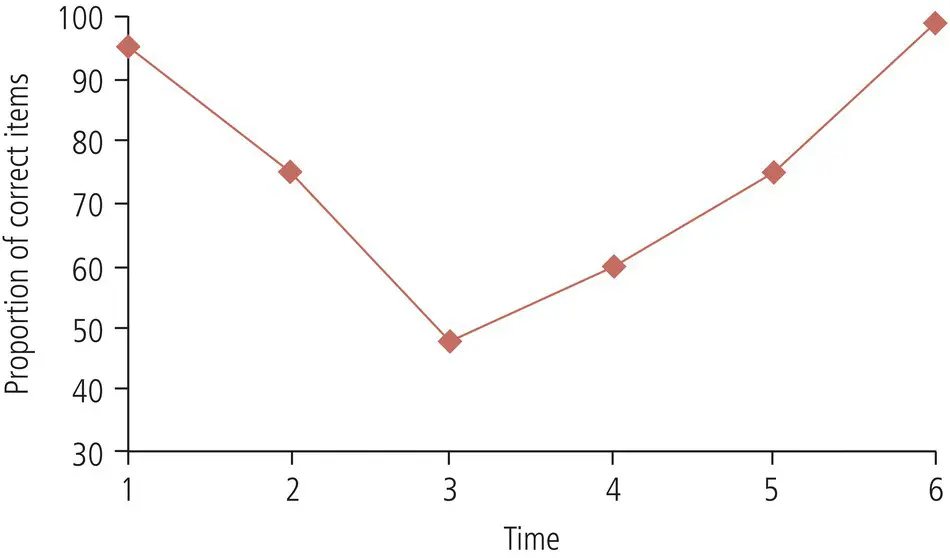

Studies also reveal that children reorganize their growing grammatical knowledge in systematic ways. For instance, children may produce a correct irregular form, such as “went,” early on, then overregularize or overgeneralize the form as “goed,” only to finally produce once again the correct target form “went.” This can be illustrated by a U‐shaped curve as can be seen in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4 U‐shaped curve representing the learning of irregular grammatical items.

Children's knowledge of language continues to develop throughout childhood and adolescence, but, remarkably, by the age of five or six, complex syntactic constructions and virtually the entire phonological repertoire of their language are well in place in most children.

One basic fundamental distinction underlying various theoretical views about L1 acquisition revolves around the extent to which language is viewed as basically the result of innate processes, i.e. nativismor a nativist view, and the extent to which environmental factors are considered as primarily responsible, i.e. empiricismor an empiricist view. This debate is far from recent: the ancient Greek philosophers were interested in the same distinction. Plato proposed that humans are born with certain “innate ideas,” while Aristotle mused about the “blank slate” that marks a person's coming into the world.

nativism

A theoretical approach emphasizing the innate, possibly genetic, contributions to any behavior.

empiricism

Theoretical view that emphasizes the role of the environment and experience over that of innate ideas or capacities.

B. F. Skinner (1904–1990), an American psychologist, was perhaps the best known proponent of an extreme empiricist, or behaviorist, view of language acquisition, known as behaviorism. He viewed the child as a passive recipient, subjected to environmental influences. In this view, language was considered as “verbal behavior,” and only what was observable and measurable was accepted as a means to evaluate language acquisition; no attempt was made to hypothesize about non‐perceptible mental events. Behaviorists such as Skinner explained vocabulary comprehension through “classical conditioning,” or the pairing of a stimulus and a response. In concrete terms, Skinner proposed that when an infant hears the word “milk” on receiving his bottle, he comes to associate the word “milk” with that nutritive substance. Along the same lines, productive vocabulary is explained by “operant conditioning”: when the child utters a word that produces the desired effect, then the child is more likely to reproduce that word and, in contrast, words that do not trigger hoped‐for responses tend to disappear. For example, if a child says “mama” in the mother's presence, the child is reinforced by receiving the desired attention. On the other hand, if the child says “mama” when the mother is not present, the link between the word and its referent is not reinforced. Eventually the child's mother becomes the stimulus evoking the response “mama,” such that a bond is established between the mother and the word “mama.” This approach also anticipates a role for direct imitation. Imitation is considered to be self‐reinforcing, and allows a shortcut so that tedious shaping of each verbal response is not necessary.

Читать дальше