Since SLA is an area of study that is increasingly recognized as relevant to a number of disciplines, I have attempted to write this book so that it will be accessible to any undergraduate or graduate student needing a basic introduction to the field. I hope it is also accessible to the general reader without a specialized academic background who is simply interested in learning more about SLA.

We will begin this exploration by looking at L1 acquisition. I hope you enjoy the journey!

1 Ortega, L. (2009). Understanding Second Language Acquisition. London: Hodder Education.

2

First Language Acquisition

Anyone concerned with the study of human nature and human capacities must somehow come to grips with the fact that all normal humans acquire language, whereas acquisition of even its barest rudiments is quite beyond the capacities of an otherwise intelligent ape.

Source: Chomsky, N., Language and Mind. © 1968, Harcourt.

1 2.1 Chapter overview

2 2.2 From sound to word

3 2.3 From word to sentence

4 2.4 Theoretical views 2.4.1 Behaviorist view 2.4.2 Universal Grammar 2.4.3 L1 interactionist approach 2.4.4 Emergentism: Connectionist viewpoint

5 2.5 First language vs second language acquisition 2.5.1 L1 acquisition vs L2 acquisition contrasts 2.5.2 L1 and L2 acquisition parallels

6 2.6 Summing up

7 Key concepts

8 Self‐assessment questions

9 Discussion questions

10 Exercises / Project ideas

11 References

12 Further reading and viewing

Gain a basic understanding of:

The L1 acquisition process and underlying theoretical views

Contrasts and similarities between L1 and L2 acquisition

The term “second language acquisition” suggests that a first language (L1) has already been acquired. Having a basic knowledge about L1 acquisition, an ability that is an essentially universal aspect of the general human condition, can be considered as fundamentally important in order to better understand second language (L2) acquisition. This chapter will begin by providing a basic description of L1 development and by presenting theoretical views proposed to explain the processes underlying that development. The second part of this chapter will present some of the dimensions along which L2 acquisition differs from or parallels the L1 acquisition process.

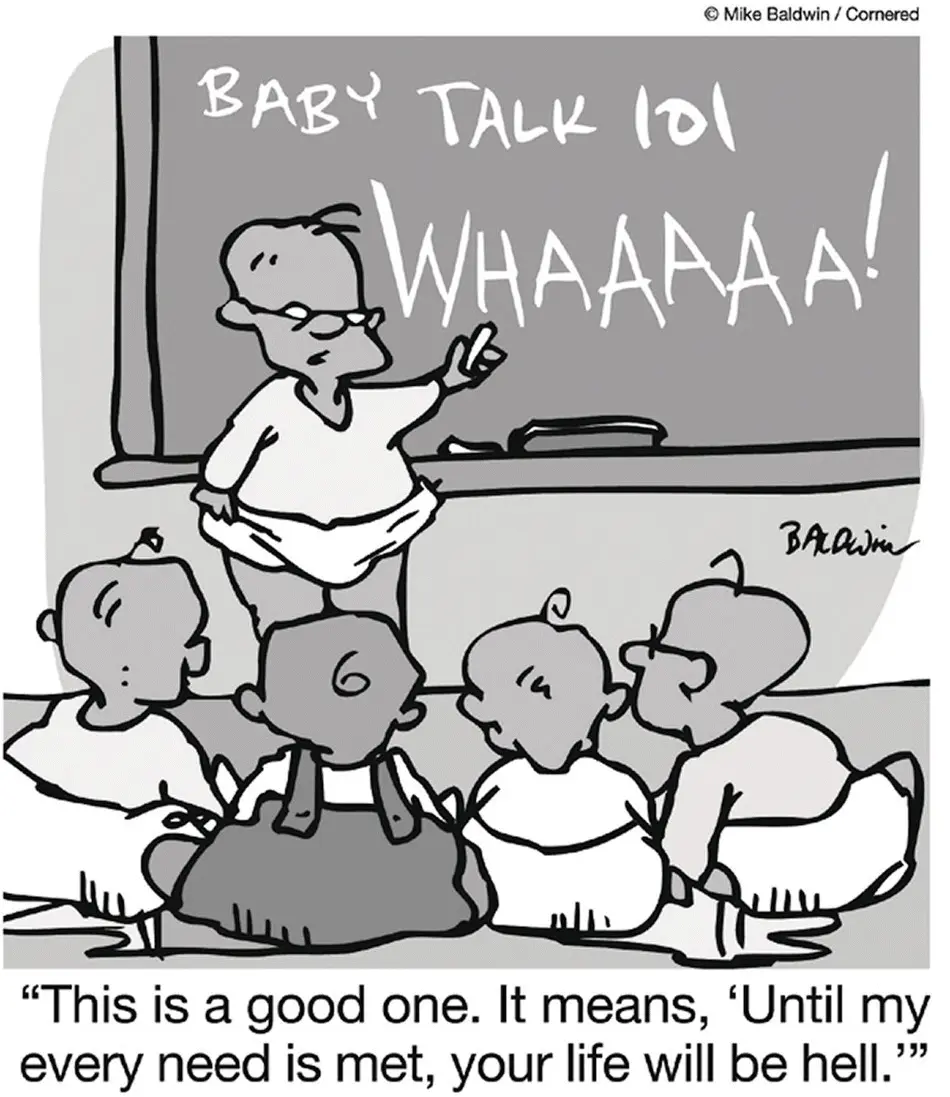

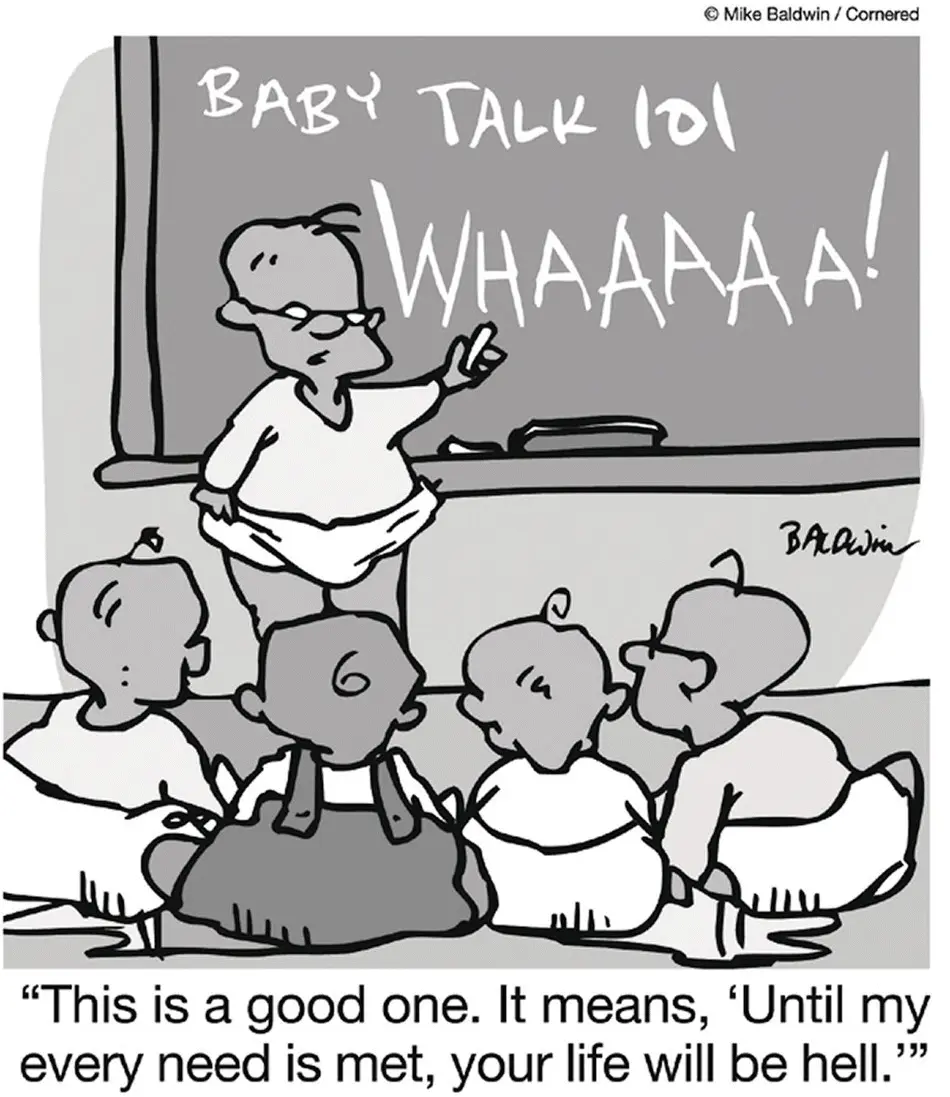

Babies are born into the world unable to linguistically articulate specific desires, needs, feelings, or intentions. However, as anyone who has had any experience with infants realizes, babies do manage to communicate in very vocal and physical ways, through various forms and intensities of crying, cooing, other sounds, and by using physical movements and gestures. In the space of a few short months, such responses come to be gradually replaced by more language‐like sounds and by 12 months of age many children are already uttering their first words.

Considerable research has gone into examining the L1 acquisition process and much of this information reveals that infants appear to come into the world equipped to acquire the language they are exposed to in their environment. Linguists often use the term “prewired” to describe this state of readiness. In fact, many linguists argue that innate structures are the only reasonable explanation for the rapidity of development and universality of stages that characterize L1 acquisition. Noam Chomsky, the pre‐eminent linguist of our times, uses the analogy of a child “learning” to walk: the child does not need to be taught to walk, he or she simply begins to put one foot ahead of the other, as soon as the child is able to stand erect (Searchinger 1995). Similarly, acquiring the language used in one's environment unfolds in the same way: children do not need to be deliberately “taught” to speak, they simply begin to do so.

Substantial evidence supports the idea of a genetic predisposition for language. For instance, a number of studies have shown that infants show a preference for the human voice, and in particular for the mother's voice, as young as three days old (DeCasper and Fifer 1980). The preferences of very young infants can be measured using a technique known as high amplitude sucking ( HAS ). In this technique, infants are exposed to sounds while their sucking rate on a pacifier is measured; an increase in rate is thought to indicate increased interest as well as the infant's detection of a stimulus difference. This technique therefore capitalizes on several facts: babies like to hear sounds; they lose interest when a sound is presented repeatedly; and they regain interest when a new sound is presented. The HAS technique is reliable from approximately one to four months of age.

high amplitude sucking (HAS)

A technique used to study infant perceptual abilities; typically involves recording an infant's sucking rate as a measure of its attention to various stimuli.

Cartoon 2.1Mike Baldwin/CartoonStock.com.

The HAS technique has revealed that newborns prefer speech sounds to non‐speech sounds (Vouloumanos and Werker 2007). Young infants also prefer looking at the human face, and prefer gazing at mouth movements that move in synchrony with the speech produced by those movements. The groundwork for conversational interaction is apparent in the early gaze‐coupling, or eye contact, behavior between the caregiver and the infant. Even at early pre‐verbal stages, interactional patterns characterize infant–caregiver communication; for example, infants wait for adult vocalizations in response to their own, and their sounds become more speech‐like following adult speech addressed to them.

Another remarkable finding is that young children from many different cultures and languages of origin are able to perceive a multitude of sound differences, even those not occurring in the language of their environment, an ability known as “sound” or “auditory discrimination,” while adults are often unable to differentiate those same sounds if they are not used in the native language. However, by the ages of 10–12 months, this sound discrimination ability already begins to disappear if the distinction is not reinforced as a part of the language spoken in that child's environment. For instance, in a study involving adults and infants, researchers (Werker and Tees 1984) examined a contrast occurring in Hindi which involved dental (tongue against the teeth) and retroflex (with the tongue curled back in the mouth) variants of the sound “t” (/t/ vs /ṭ/), a contrast that does not occur in English. While Hindi‐speaking adults are able to perceive this sound difference without difficulty, English‐speaking adults generally are unable to do so. Werker and Tees examined children's perceptual abilities for the Hindi contrast, as well as for a Salish (a language spoken by First Nations people in British Columbia) contrast between two consonantal sounds produced in the back part of the mouth: velar /k'i/and uvular /q'i/. This experiment focused on head‐turning responses of young infants (infants are found to turn their head when they detect a novel stimuli), and the researchers found that six‐ to eight‐month‐old English‐speaking infants were able to perceive the Hindi contrast, as well as the Salish contrast. However, by 8–10 months, the infants could no longer perceive the Salish contrast. And by 10–12 months of age, the children no longer perceived the Hindi contrast either. In contrast, children from native Hindi‐ and Salish‐speaking families continued to perceive the contrasts occurring in their native languages. The results for English L1 and Hindi L1 infant perception of Hindi contrasts are illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Читать дальше