For both types of language learners, typical errors occur that indicate that learners are attempting to increase their mastery by relying on information they already know, or overgeneralization. A young child may say “mouses” for “mice,” thereby applying the regular plural suffix “–s” (cf. “houses,” “toys,” etc.) on a noun constituting an exception to the rule. Similarly, the adult L2 learner may overgeneralize parts of the grammar as when a beginning learner of Spanish says “ Tiene hambre ” (“He or she is hungry”), using the form “ tiene ,” normally used for third person singular forms instead of the correct “ Tengo hambre ” form used only for first person singular (“I'm hungry”). These examples of overgeneralization are further illustrations that there is much that is systematic in both L1 and L2 learning. In both instances, individuals appear to be learning in a structured, organized fashion: they develop a rule system that governs their utterances, and these rules can change as their linguistic system develops. Learners extrapolate their newly encountered grammatical rules to contexts which do not follow the rules, as in the “mouses” and “tiene” examples cited above.

overgeneralization

The use of a rule or structure in contexts in which it is not appropriate; for example, “I hurted my arm.”

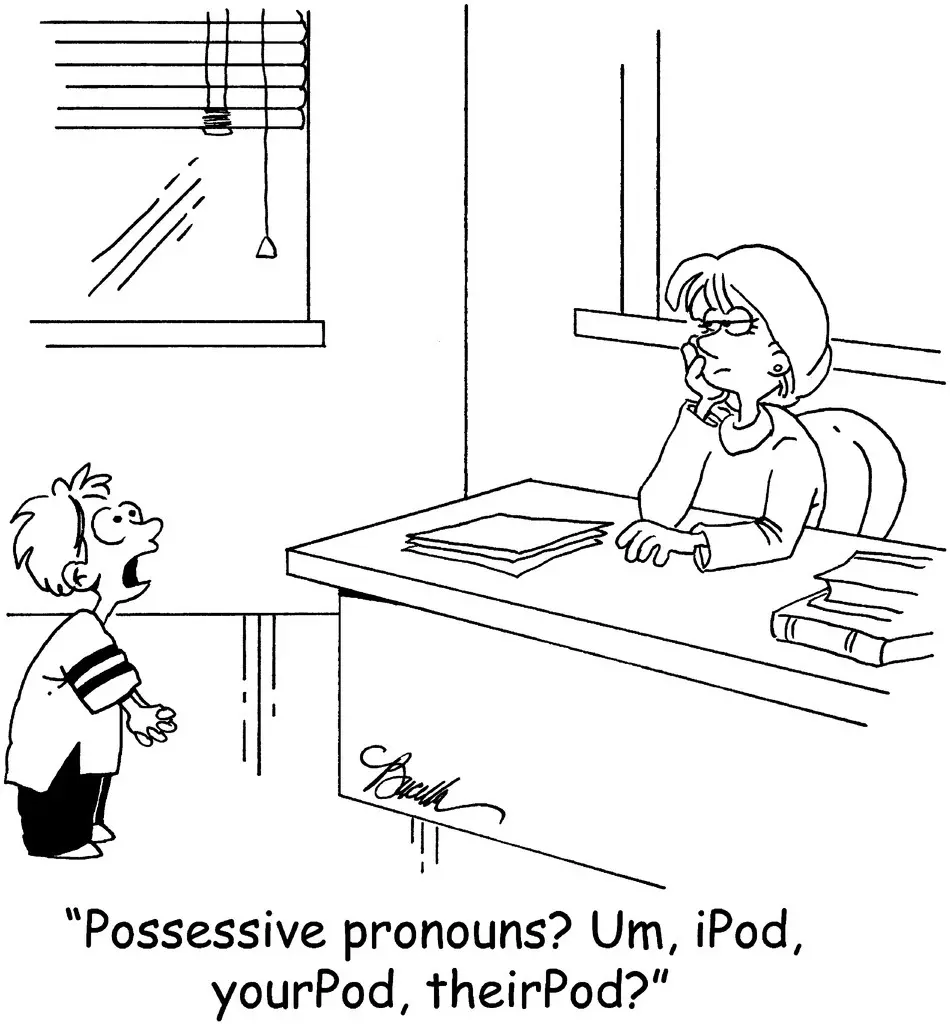

Further, young children begin by listening and speaking and only learn literacy‐related skills such as reading and writing (or descriptive grammar, as illustrated in the cartoon) once they reach school age. In fact, in some societies, literacy skills are never developed by a substantial proportion of the population, or only to a limited extent. Yet all children without significant cognitive disabilities learn to carry on fluent conversations in the language of their environment. In parallel, to a large extent it remains common for L2 learners to begin in a similar fashion, by engaging in listening and speaking skills before mastering reading and writing skills, although, as pointed out in the previous section, L2 learners can and do opt to use their literacy skills to learn the language. Traditionally, many teaching approaches reinforced this sequence, to the extent that some L2 methods almost banished written material from beginning language classrooms in the mid‐twentieth century.

Cartoon 2.3Marty Bucella/CartoonStock.com.

This chapter has pointed out considerable evidence that innate structures offer a reasonable explanation for the rapidity of development and universality of stages that characterize L1 acquisition. Babbling occurs early on, and at approximately the first year mark, the child's first recognizable word may appear. At around the 50‐word vocabulary mark, children appear to begin to string two words together, and vocabulary and grammatical development accelerates thereafter. Children's grammatical development has been measured in terms of MLU, calculated in terms of morphemes per utterance. Brown (1973) found that children differ in rate of MLU development, although they acquire forms in a similar order. It has also been established that children tend to make typical errors, including overgeneralizing rules, as in using “mouses” instead of “mice.” They also may go through a period in which word meanings are overextended (“dog” for all four‐footed animals) and/or underextended (“dog” only for the family pet).

There are considerable differences in learning a first language as an infant and learning a second language after a first language has been acquired. Many of the differences are related to age and cognitive developmental factors. Others are related to the very fact that for L2 acquisition one language is already available to enable basic communication and the expression of needs and desires. On the other hand, despite these remarkable differences, there is much about the two processes that is similar: similar patterns of development, similar errors, similar strategies that mark developmental stages. As we continue to explore second language acquisition, an awareness of these differences and similarities should permit a better understanding of the challenges faced by the second language learner.

High amplitude sucking (HAS)

Reduplicated babbling

Nonreduplicated (variegated) babbling

Overextension

Underextension

Morphemes

Mean length of utterance (MLU)

Input

Nativism

Empiricism

Behaviorism

Universal Grammar (UG)

Interactionism

Child‐directed speech (CDS)

CHILDES

Emergentism

Connectionism

Object permanence

Metalinguistic awareness

Transfer

Interference

Overgeneralization

Formulaic sequences/expressions

self‐assessment questions

1 The ability to discriminate sounds not used in the L1 seems to:be lost by one month of agebe lost by three to four months of agebe lost by 10–12 months of ageremain available until school age.

2 Which of the following is NOT considered to be a key stage in L1 acquisition?babblingone‐word stagetwo‐word stagethree‐word stage.

3 Brown's (1973) study on the order of acquisition of certain grammatical morphemes in English primarily revealed that:children acquire morphemes in different orderschildren acquire morphemes at different ratesboth a and bnone of the above.

4 CHILDES is:a computerized database of child speech transcriptsa computer program for teaching children new wordsthe name of an important child language researchernone of the above.

5 When we say that children's early multiword utterances are “telegraphic,” we mean they:are immediately understoodinclude many content words and few function wordsinclude many function words and few content wordsare produced in a flat, mechanical tone of voice.

6 Most children begin combining words into multiword utterances when their productive vocabulary includes about:10 words50 words150 words250 words.

1 It is argued that children do not receive explicit correction when they use ungrammatical forms. Do you agree with this claim? Why or why not? Are there other ways in which children might get feedback or come to realize that their utterances are not grammatical?

2 To what extent do you think there are individual differences affecting children's acquisition of their first language? Based on your own personal experience, have you encountered any differences, such as with regard to rate of L1 acquisition, among children you know?

3 Do you know what was the first word or words that you produced? If so, does that word or words resemble the first words produced by others in your class? What might explain which words are the first to appear in a child's vocabulary?

exercises / project ideas

1 Using the guidelines found below based on Brown (1973), calculate the MLU for one of the CHILDES transcripts found online ( http://childes.talkbank.org). Select a transcript involving a child between the ages of one and three years of age (ages are indicated at the beginning of each transcript). (Note that a sample shorter than 100 utterances may be used, although Brown recommends a 100‐utterance length.)

1 Use 100 intelligible utterances of a child language transcript.

2 Count the morphemes as indicated in the guidelines below.

3 Add the total number of morphemes and divide by the total number of utterances (100) to get the MLU.

Читать дальше