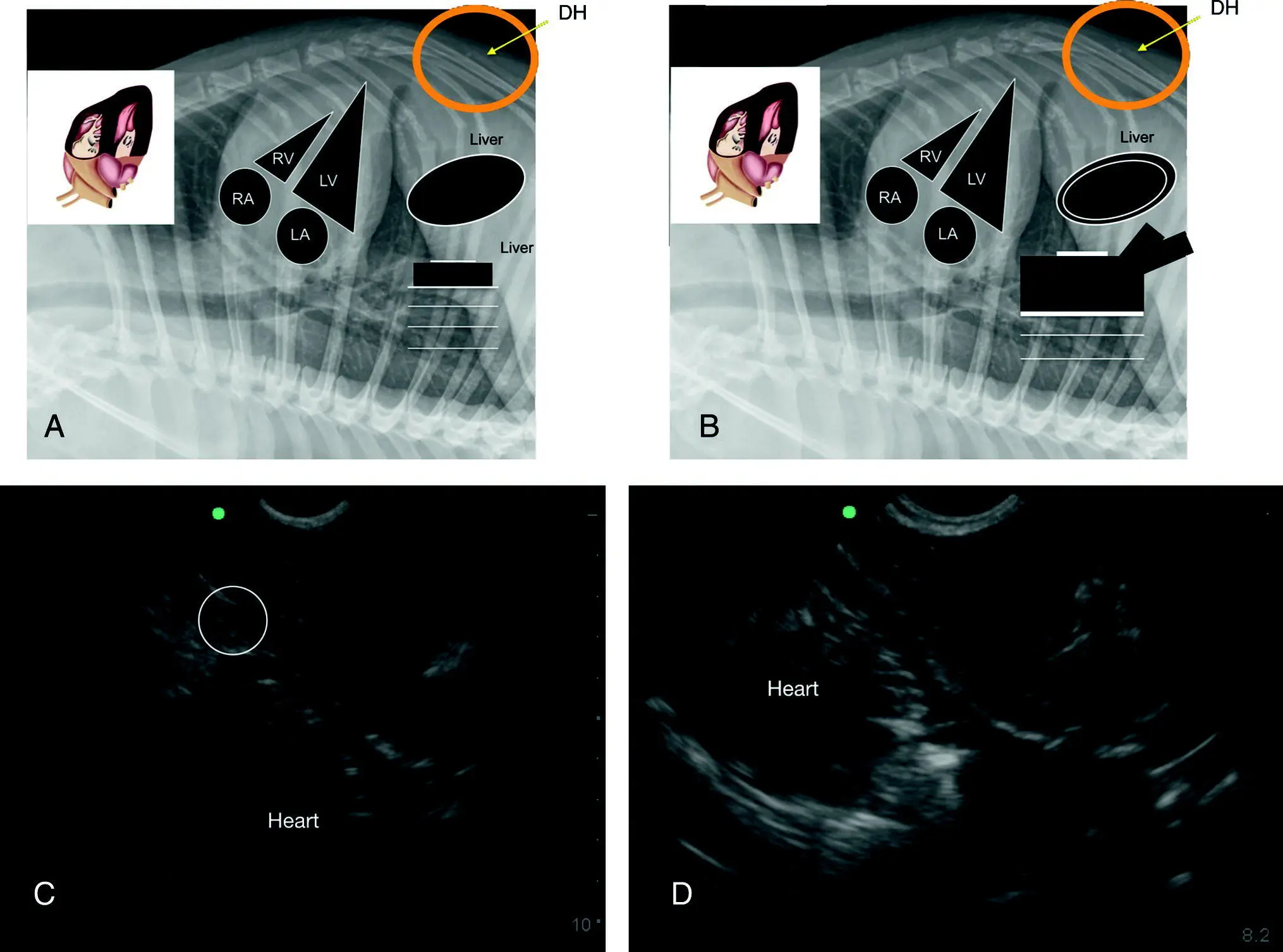

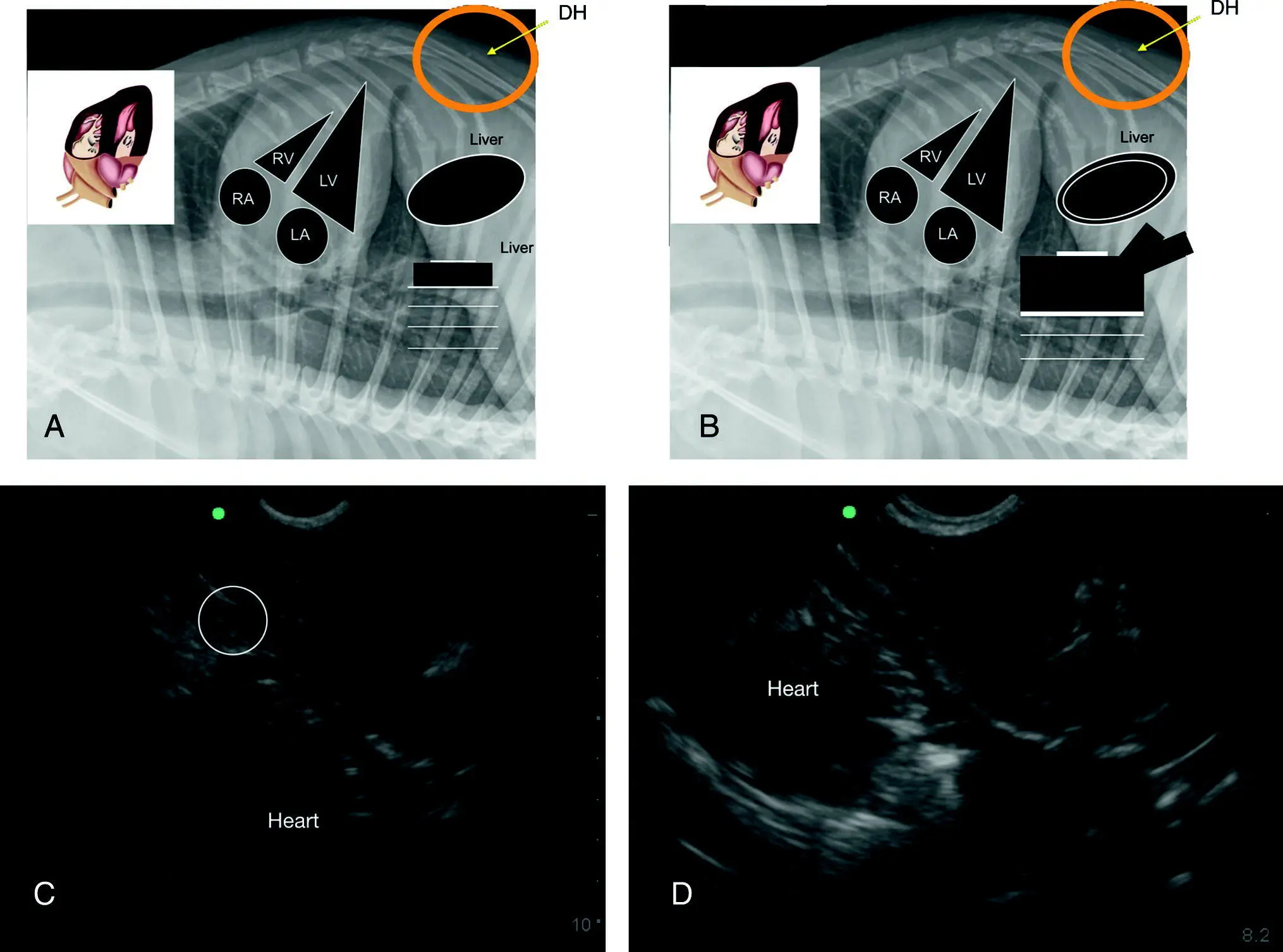

Figure 7.13. The racetrack sign of PCE with integration of the CVC characterization. (A,B) Inverted lateral thoracic radiographs to illustrate the anatomy in the ultrasound images in (C) and (D) with PCE evidenced by the rounding of anechoic fluid, referred to as the “racetrack sign” (Lisciandro 2014a,b, 2016a). Characterization of the CVC is helpful for evidence that obstructive shock and tamponade may be present. In (A) the CVC is unremarkable and in (B) the CVC is “FAT” and has associated hepatic venous distension supporting obstruction of blood flow to the right atrium. In (C) there is a small‐volume ascites ( circled ) and if a modified transudate, supports a more chronic case of PCE and a better prognosis. In (B) gallbladder wall edema, the “cardiac gallbladder,” is shown which is only expected with hepatic venous congestion and more chronicity to the PCE.

Source: Reproduced with permission of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

Interestingly, the use of IVC distension (a “FAT” IVC) in people is only about 40% specific for the presence of cardiac tamponade. Conversely, a nondistended IVC at the subxiphoid view that has its expected normal variation in diameter in spontaneously breathing people effectively rules out cardiac tamponade with a sensitivity of 97% (Candotti and Arntfield 2015; Tchernodrinski and Arntfield 2015). The CVC in small animals likely proves similarly helpful with indirect nonechocardiographic (fallback view) information regarding the presence of obstructive shock from cardiac tamponade. We like the saying “Don't risk your patient's life trying for an echo view” – use the Global FAST fallback views (see Figure 36.7).

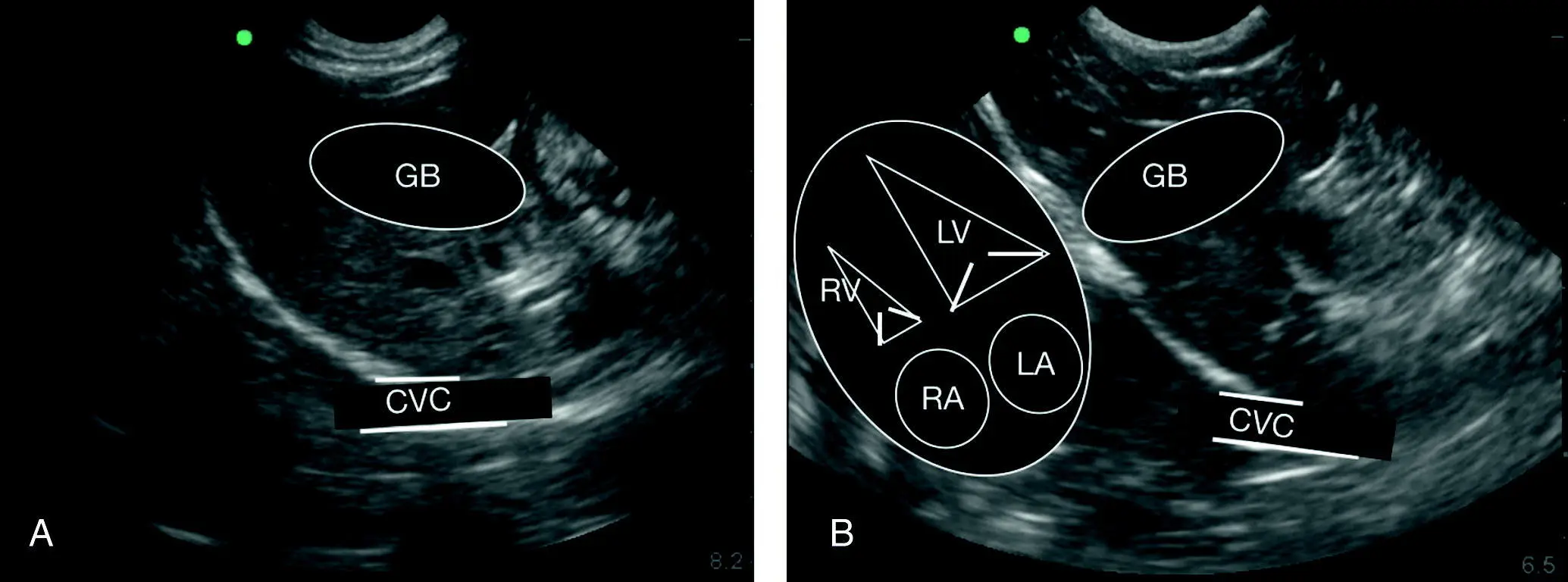

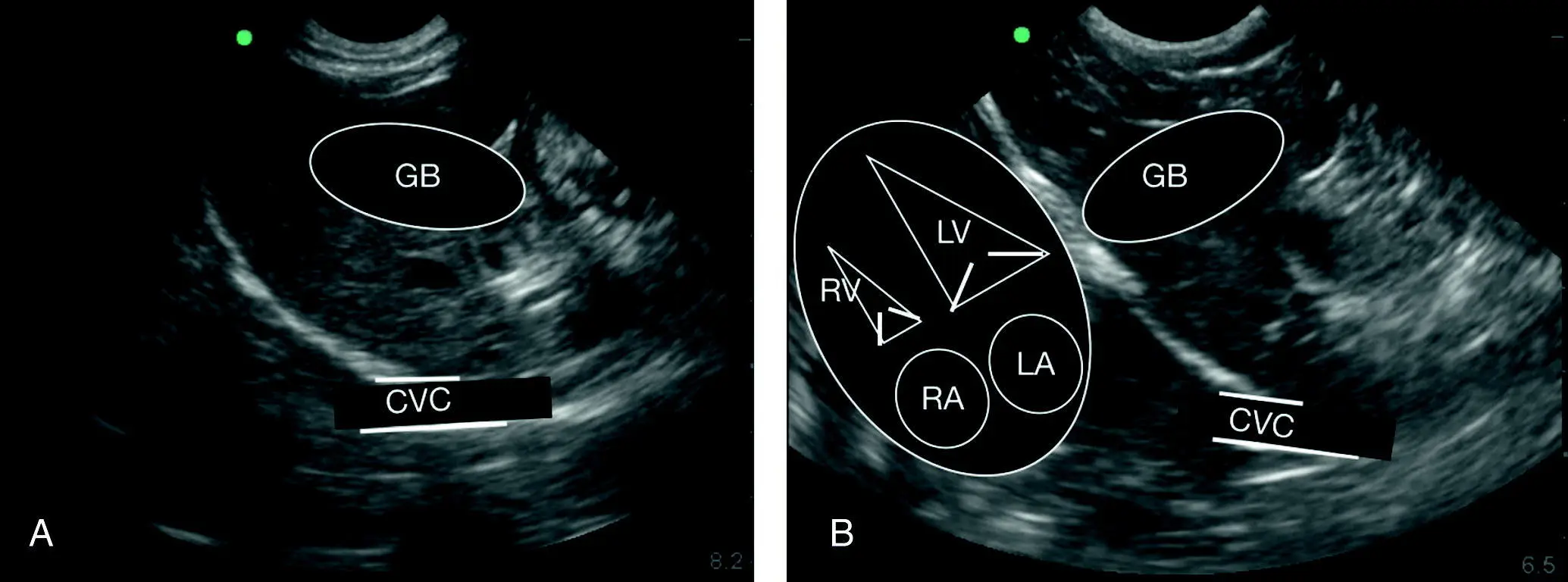

Figure 7.14. Relative positioning of gallbladder to diaphragm to caudal vena cava. (A,B) Line drawing overlays of the gallbladder (GB) and caudal vena cava (CVC). In (A) the heart is faintly visible on the still image analogous to the overlay in (B). In real time the beating heart is readily apparent. (B) Orientation of the heart as it lies against the diaphragm in both dogs and cats. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. The orientation and proportionality in the longitudinal plane are nearly identical independent of standing/sternal versus right lateral recumbency.

Source: Reproduced with permission of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

Pearl:Always look cranial to the diaphragm because most cases of clinically relevant pericardial effusion are detected via the DH view, which is part of AFAST, TFAST, and Vet BLUE.

Pearl:Ascites (modified transudate) in cases of PCE cases carries a better prognosis because the PCE has been a more chronic process in that patient (Johnson et al. 2004). Always stage with Global FAST and encourage pericardiocentesis when indicated in these cases.

Pearl:The nonecho option for the presence or absence of cardiac tamponade is characterization of the CVC. A “bounce” to the CVC rules out tamponade versus a “FAT” distended CVC which supports the presence of obstructive shock and cardiac tamponade and the need for emergent pericardiocentesis in weak, collapsed patients, although it's best to look at the patient to make that final decision (stable, can wait; unstable, needs emergent pericardiocentesis).

Prevalence of Pericardial Effusion

Pericardial effusion brings up a fascinating change in teaching paradigms because a more effective first‐line screening test is being used since the FAST movement began in 2004 (Boysen et al. 2004; Lisciandro 2014a,b, 2016a). We were screening with less sensitive imaging, using thoracic radiography, an unreliable test (Guglielmini et al. 2012; Côté et al. 2013; Lisciandro 2016a). Before FAST, the patient was only diagnosed if they were scheduled for echocardiography or CT. As a case in point, the author's practice documented three cases of PCE in 2005 before AFAST‐TFAST and 28 cases in 2012 (Lisciandro 2014a,b, 2016a). Why the difference? Simply, we were using the wrong test (Guglielmini et al. 2012; Côté et al. 2013). Ultrasound is arguably the gold standard test for PCE.

Causes of Pericardial Effusion

So now fast forward through 15 years of AFAST and TFAST. Using ultrasound as a first‐ line screening test, veterinarians (and physicians) are now capturing PCE cases that would have otherwise been missed (Lisciandro 2014a,b, 2016a). However, what we are finding with the paradigm change is that there are two subsets of PCE, acute and chronic, and they are remarkably different ( Table 7.8).

In the past, a feline or canine patient may have had acute PCE and cardiac tamponade but with radiography dominating as first‐line imaging, the unremarkable or equivocal cardiac silhouette missed the PCE because many patients were never scheduled for echocardiography. The patient, with or without help from the attending clinician, often declared themselves survivors or nonsurvivors despite care. In those that survived, the patient likely compensated, stretched its pericardium over time before developing the classic globoid heart and ascites, representing as weak with abdominal distension from ascites and generally stable. Pericardiocentesis was more commonly an elective procedure with high success due to PCE chronicity. In this patient subset, the findings of electrical alternans, pulsus paradoxicus, muffled heart sounds, and a globoid heart on thoracic radiography were possible, although with variable reliability (Johnson et al. 2004).

Table 7.8. Most common causes of pericardial effusion in dogs and cats.

Source: Reproduced with permission of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

| Dogs a |

Cats c |

| Neoplasia b(~70%) |

Congestive heart failure (≥75%) |

| Idiopathic (~20%) |

Idiopathic |

| Right‐sided congestive heart failure |

Lymphoma |

| Left atrial tear/rupture |

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) |

| Anticoagulant rodenticides |

Hyperthyroidism |

| Foreign body (plant awn, porcupine quill, projectile, other) |

Uremia |

| Infectious (bacterial, fungal) |

Infectious (fungal, bacterial) |

| Peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia |

Peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia |

| Pericardial cyst |

Sepsis |

| Uremia |

|

| Trauma |

|

aAscites is a more favorable diagnosis with median survival reported to be 605 days compared to 45 days in dogs without ascites (Johnson et al. 2004), thus Global FAST should be done first line.

b~50–60% have metastatic disease at time of diagnosis (MacDonald et al. 2009), thus Global FAST should be done first line.

cMost common cause in cats is congestive heart failure and most common heart disease is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Hall et al. 2007).

Data from Hall et al. (2007); Davidson et al. (2008); Shaw and Rush (2007); MacDonald et al. (2009); Ward et al. (2018).

Nonhemoabdomen Ascites Carries a Better Prognosis

The Global FAST approach is imperative for PCE cases, especially in dogs in which nonhemoabdomen ascites (and echo negative for a mass) has been shown to carry a much more favorable prognosis, with median survival times much different at 605 days versus 45 days (Stafford Johnson et al. 2004). The presence of a mass (echo‐positive versus echo‐negative) also has great influence on the prognosis, with similar large differences in survival between those without echo‐detected masses and those with – 1068 days versus 26 days (Stafford Johnson et al. 2004). Furthermore, in the large study done by MacDonald and colleagues, of those with masses, no matter the type of tumor, metastasis was high (~50–66%) and thoracic radiography only detected ~33% of lung metastasis (MacDonald et al. 2009). Global FAST with its target organ approach has the potential to detect intraabdominal metastasis as well as pulmonary, and Vet BLUE has been shown to perform better than thoracic radiography in a pilot study (Kulhavy and Lisciandro 2015) (see Chapter 36).

Читать дальше