1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...40 In 1451, by the will of Phillip Malpas, who had been a sheriff some twelve years previous, the sum of £125 was bequeathed to “the relief of poor prisoners.” This Malpas, it may be mentioned here, was a courageous official, ready to act promptly in defence of city rights. In 1439 a prisoner under escort from Newgate to Guildhall was rescued from the officer’s hands by five companions, after which all took sanctuary at the college of St. Martin’s-le-Grand.[23] “But Phillip Malpas and Robert Marshal, the sheriffs of London, were no sooner acquainted with the violence offered to their officer and the rescue of their prisoner, than they, at the head of a great number citizens, repaired to the said college, and forcibly took from thence the criminal and his rescuers, whom they carried in fetters to the Compter, and thence, chained by the necks, to Newgate.”

For food the prisoners were dependent upon alms or upon articles declared forfeit by the law. Thus some bread of light weight, seized on the 10th August 1298, was ordered to be given to the prisoners in Newgate. Again, the halfpenny loaf of light bread of Agnes Foting of Stratford was found wanting 7 shillings (or 4⅕ oz.) in weight; therefore it was adjudged that her bread should be forfeited, and it also was sent unto the gaol. All food sold contrary to the statutes of the various guilds was similarly forfeited to the prisoners. The practice of giving food was continued through succeeding years, and to a very recent date. A long list of charitable donations and bequests might be made out, bestowed either in money or in kind. A customary present was a number of stones of beef. Some gave penny loaves, some oatmeal, some coals. Without this benevolence it would have gone hard with the poor population of the Gatehouse gaol. It was not strange that the prison should be wasted by epidemics, as when in 1414 “the gaoler died and prisoners to the number of sixty-four;” or that the inmates should at times exhibit a desperate turbulence, taking up arms and giving constituted authority much trouble to subdue them, as in 1457 when they broke out of their several wards in Newgate, and got upon the leads, where they defended themselves with great obstinacy against the sheriffs and their officers, insomuch that they, the sheriffs, were obliged to call the citizens to their assistance, whereby the prisoners were soon reduced to their former state.

The evil effects of incarceration in Newgate may be further judged by the fate which overtook the city debtors who were temporarily removed thither from Ludgate. An effort had been made in 1419 to put pressure upon them as a class. An ordinance was issued by Henry V. closing the Ludgate prison for debtors. It had been found that “many false men of bad disposition and purpose have been more willing to take up their abode there, so as to waste and spend their goods upon the ease and license that there is within, than pay their debts.” Wherefore it was ordained that “all prisoners therein shall be removed and safely carried to Newgate, there to remain each in such keeping as his own deserts shall demand.” The order was, however, very speedily rescinded. A later ordinance in the same year sets forth that “whereas, through the abolition and doing away with the prison of Ludgate, which was formerly ordained for the good and comfort of citizens and other reputable persons, and also by reason of the fœtid and corrupt atmosphere that is in the hateful gaol of Newgate, many persons who lately were in the said prison of Ludgate, who in the time of William Sevenoke, late mayor, for divers great offences which they had there compassed were committed to the said gaol (of Newgate), are now dead, who might have been living, it is said, if they had

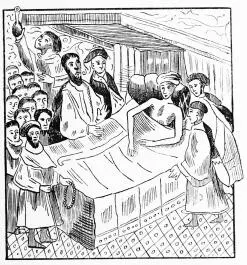

The Gaoler

remained at Ludgate abiding in peace there; and seeing that every person is sovereignly bound to support and be tender to the lives of men, the which God hath bought so dearly with His precious blood; therefore Richard Whittington, now mayor (1419), and the aldermen, on Saturday the 2nd November, have ordained and established that the gaol of Ludgate shall be a prison from henceforth to keep therein all citizens and other reputable persons whom the mayor, aldermen, sheriffs, or chamberlain of the city shall think proper to commit and send to the same, provided always that the warder shall be a good and loyal man, giving sufficient surety,” &c. Ten or twelve years later a similar exodus from Ludgate to Newgate and back again took place. “On the Tuesday next after Palm Sunday 1431, all the prisoners of Ludgate were conveyed into Newgate by Walter Chartsey and Robert Large, sheriffs of London, and on the 13th April the same sheriffs (through the false suggestion of John Kingesell, gaoler of Newgate) did fetch from thence eighteen persons, freemen, and these were led to the Counters pinioned as if they had been felons. But on the 16th June Ludgate was again appointed for freemen, prisoners for debt, and the same day the same freemen entered by ordinance of the mayor, aldermen, and commons; and by them Henry Deane, tailor, was made keeper of Ludgate.”

One other charitable bequest must be referred to here, as proving that the moral no less than the physical well-being of the prisoners was occasionally an object of solicitude. In the reign of Richard II. a prayer-book was specially bequeathed to Newgate in the following terms:—

“Be it remembered that on the 10th day of June, in the 5th year (1382), Henry Bever, parson of the church of St. Peter in Brad Street (St. Peter the Poor, Broad Street), executor of Hugh Tracy, Chaplain, came here before the mayor and aldermen and produced a certain book called a ‘Porte hors,’[24] which the same Hugh had left to the gaol of Newgate, in order that priests and clerks there imprisoned might say their service from the same, there to remain so long as it might last. And so in form aforesaid the book was delivered unto David Bertelike, keeper of the gate aforesaid, to keep it in such manner so long as he should hold that office; who was also then charged to be answerable for it. And it was to be fully allowable for the said Henry to enter the gaol aforesaid twice in the year at such times as he should please, these times being suitable times, for the purpose of seeing how the book was kept.”[25]

We are without any very precise information as to the state of the prison building throughout these dark ages. But it was before everything a gate-house, part and parcel of the city fortifications, and therefore more care and attention would be paid to its external than its internal condition. It was subject, moreover, to the violence of such disturbers of the peace as the

Death-bed of Whittington.

followers of Wat Tyler, of whom it is written that, having spoiled strangers “in most outrageous manner, entered churches, abbeys, and houses of men of law, which in semblable sort they ransacked, they also brake up the prisons of Newgate and of both the Compters, destroyed the books, and set the prisoners at liberty.” This was in 1381. Whether the gaol was immediately repaired after the rebellion was crushed does not appear; but if so, the work was only partially performed, and the process of dilapidation and decay must soon have recommenced, for in Whittington’s time it was almost in ruins. That eminent citizen and mercer, who was three times mayor, and whose charitable bequests were numerous and liberal, left moneys in his will for the purpose of rebuilding the place, and accordingly license was granted in 1422, the first year of Henry VI.’s reign, to his executors, John Coventre, Jenken Carpenter, and William Grove, “to re-edify the gaol of Newgate, which they did with his goods.” This building, such as it was, continued to serve until the commencement of the seventeenth century.

Читать дальше