Henry was, however, impartial in his severity. In 1533 he suffered John Frith, Andrew Hewett, and other Protestants, to the number of twenty-seven, to be burned for heresy. The years immediately following he hunted to death all who refused to acknowledge him as the head of the Church. Besides such imposing victims as Sir Thomas More, and Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, many priests suffered. In 1534 the prior of the London Carthusians, the prior of Hexham, Benase, a monk of Sion College, and John Haite, vicar of Isleworth, together with others,[37] were sentenced to be hanged and quartered at Tyburn. In 1538 a friar, by name Forrest, was hanged in Smithfield upon a gallows, quick, by the middle and armholes, “and burnt to death for denying the king’s supremacy and teaching the same in confession to many of the king’s subjects.” Upon the pile by which Forrest was consumed was also a wooden image, brought out of Wales, called “Darvell Gatheren,” which the Welshmen “much worshipped, and had a prophecy amongst them that this image would set a whole forest on fire, which prophecy took effect.”[38]

The greatest trials were reserved for the religious dissidents who dared to differ with the king. Henry was vain of his learning and of his polemical powers. No true follower of Luther, he was a Protestant by policy rather than conviction, and he still held many tenets of the Church he had disavowed. These were embodied and promulgated in the notorious Six Articles, otherwise “the whip with six tails,” or the Bloody Statute, so called from its sanguinary results. The doctrines enunciated were such that many could not possibly subscribe to them; the penalties were “strait and bloody,” and very soon they were widely inflicted. Foxe, in a dozen or more pages, recounts the various presentments against individuals, lay and clerical, for transgressing one or more of the principles of the Six Articles; and adds to “the aforesaid, Dr. Taylor, parson of St. Peter’s, in Cornhill; South, parish priest of Allhallows, in Lombard Street; Some, a priest; Giles, the king’s beerbrewer, at the Red Lion, in St. Katherine’s; Thomas Lancaster, priest; all which were imprisoned likewise for the Six Articles.” “To be short,” he adds, “such a number out of all parishes in London, and out of Calais, and divers other quarters, were then apprehended through the said inquisition, that all prisons in London, including Newgate, were too little to hold them, insomuch that they were fain to lay them in the halls. At last, by the means of good Lord Audeley, such pardon was obtained of the king that the said Lord Audeley, then Lord Chancellor, being content that one should be bound for another, they were all discharged, being bound only to appear in the Star Chamber the next day after All Souls, there to answer if they were called; but neither was there any person called, neither did any appear.”[39]

Bonner, then Bishop of London, and afterwards one of the queen’s principal advisers, had power to persecute even under Henry. The Bible had been set up by the king’s command in St. Paul’s, that the public might read the sacred word. “Much people used to resort thither,” says Foxe, to hear the reading of the Bible, and especially attended the reading of one John Porter, “a fresh young man, and of a big stature,” who was very expert. It displeased Bonner that this Porter should draw such congregations, and sending for him, rebuked him very sharply for his reading. Porter defended himself, but Bonner charged him with making expositions on the text,

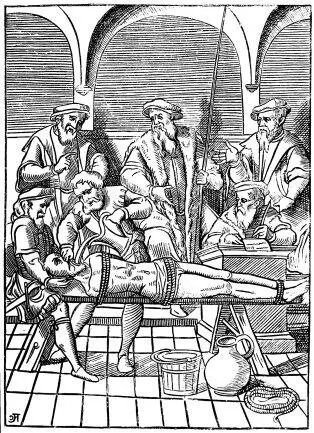

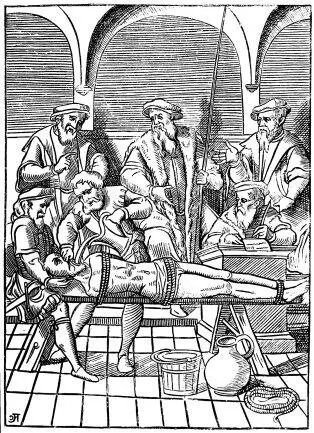

Skeffington’s Gyves.

and gathering “great multitudes about him to make tumults.” Nothing was proved against Porter, but “in fine Bonner sent him to Newgate, where he was miserably fettered in irons, both legs and arms, with a collar of iron about his neck, fastened to the wall in the dungeon; being there so cruelly handled that he was compelled to send for a kinsman of his, whose name is also Porter, a man yet alive, and can testify that it is true, and dwelleth yet without Newgate. He, seeing his kinsman in this miserable case, entreated Jewet, the keeper of Newgate, that he might be released out of those cruel irons, and so, through friendship and money, had him up among other prisoners, who lay there for felony and murder.” Porter made the most of the occasion, and after hearing and seeing their wickedness and blasphemy, exhorted them to amendment of life, and “gave unto them such instructions as he had learned of in the Scriptures; for which his so doing he was complained, and so carried down and laid in the lower dungeon of all, oppressed with bolts and irons, where, within six or eight days, he was found dead.”

But the most prominent victim to the Six Articles was Anne Askew, the daughter of Sir William Askew, knight, of Lincolnshire. She was married to one Kyme, but is best known under her maiden name. She was persecuted for denying the Real Presence, but the proceedings against her were pushed to extremity, it was said, because she was befriended in high quarters. Her story is a melancholy one. First one Christopher Dene examined her as to her faith and belief in a very subtle manner, and upon her answers had her before the Lord Mayor, who committed her to the Compter. There, for eleven days, none but a priest was allowed to visit her, his object being to ensnare her further. Presently she was released upon finding sureties to surrender if required, but was again brought before the king’s council at Greenwich. Her opinions in matters of belief proving unsatisfactory, she was remanded to Newgate. Thence she petitioned the king, also the Lord Chancellor Wriottesley, “to aid her in obtaining just consideration.” Nevertheless, she was taken to the Tower, and there tortured. Foxe puts the following words into her mouth: “On Tuesday I was sent from Newgate to the sign of the Crown, where Master Rich and the Bishop of London, with all their power and flattering words, went about to persuade me from God, but I did not esteem their glosing pretences. … Then Master

Torture in The Tower.

Rich sent me to the Tower, where I remained till three o’clock.” At the Tower strenuous efforts were made to get her to accuse others. They pressed her to say how she was maintained in prison; whether divers gentlewomen had not sent her money. But she replied that her maid had “gone abroad in the streets and made moan to the ’prentices,” who had sent her alms. When further urged, she admitted that a man in a blue coat had delivered her ten shillings, saying it came from my Lady Hertford, and that another in a violet coat had given her eight shillings from my Lady Denny—“whether it is true or not I cannot tell.” “Then they said three men of the council did maintain me, and I said no. Then they did put me on the rack because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen to be of my opinion, and thereon they kept me a long time; and because I lay still, and did not cry, my Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands till I was nigh dead. Then the lieutenant (Sir Anthony Knevet) caused me to be loosed from the rack. Incontinently I swooned, and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours, reasoning with my Lord Chancellor, on the bare floor.” At last she was “brought to a house and laid in a bed with as weary and painful bones as ever had patient Job; I thank my Lord God there-for. Then my Lord Chancellor sent me word, if I would leave my opinion, I should want nothing; if I did not, I should forthwith to Newgate, and so be burned. …”

Читать дальше