Arthur Thomas Malkin

The Gallery of Portraits

(Vol. 1-7)

With Memoirs: Complete Edition

e-artnow, 2020

Contact: info@e-artnow.org

EAN 4064066400354

Volume 1 Volume 1 Table of Contents

Volume 2 Volume 2 Table of Contents

Volume 3

Volume 4

Volume 5

Volume 6

Volume 7

Table of Contents Table of Contents Volume 1 Volume 1 Table of Contents Volume 2 Volume 2 Table of Contents Volume 3 Volume 4 Volume 5 Volume 6 Volume 7

DANTE

DAVY

KOSCIUSKO

FLAXMAN

COPERNICUS

MILTON

WATT

TURENNE

BOYLE

NEWTON

MICHAEL ANGELO

MOLIERE

FOX

BOSSUET

LORENZO DE MEDICI.

BUCHANAN

FENELON

WREN

CORNEILLE

HALLEY

SULLY

POUSSIN

HARVEY

BANKS

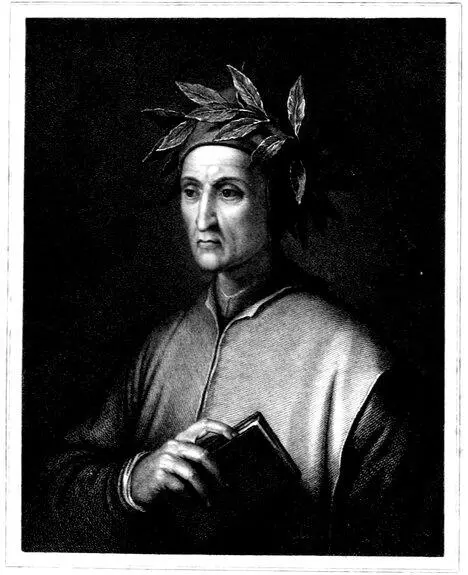

Engraved by C. E. Wagstaff. DANTE ALIGHIERI. From a Print by Raffaelle Morghen, after a Picture by Tofanelli. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London. Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

While the more northern nations of modern Europe began to cultivate a national and peculiar literature in their vernacular tongues, instead of using Latin as the only vehicle of written thought, it was some time before the popular language of Italy received that attention which might have been expected from the prevalence of free institutions, and the constant intercourse between neighbouring states speaking in similar dialects. At last the example of other countries prevailed, and a native poetry sprung up in Italy. If it be allowable to compare the progress of the national mind to the stages of life, the Italian Muse may be said to have been born in Sicily with Ciullo d’Alcamo in 1190; to have reached childhood in Lombardy with Guido Guinicelli, about 1220; and to have attained youth in Tuscany with Guido Cavalcanti, about 1280. But she suddenly started into perfect maturity when Dante appeared, surpassing all his predecessors in lyrical composition, and astounding the world with that mighty monument of Christian poetry, which after five centuries of progressive civilization still stands sublime as one of the most magnificent productions of genius.

Dante Alighieri, the true founder of Italian literature, was born at Florence A.D. 1265, of a family of some note. The name of Dante, by which he is generally known, often mistaken for that of his family, is a mere contraction of his Christian name Durante. Yet an infant when his father died, that heavy loss was lightened by the judicious solicitude with which his mother superintended his education. She intrusted him to the care of Brunetto Latini, a man of great repute as a poet as well as a philosopher; and he soon made so rapid a progress, both in science and literature, as might justify the most sanguine hopes of his future eminence.

Early as he developed the extraordinary powers of his understanding, he was not less precocious in evincing that susceptibility to deep and tender impressions, to which he afterwards owed his sublimest inspirations. But his passion was of a very mysterious character. It arose in his boyhood, for a girl “still in her infancy,” and it never ceased, or lost its intensity, though she died in the flower of her age, and he survived her more than thirty years. Whether he was enamoured of a human being, or of a creature of his own imagination—one of those phantoms of heavenly beauty and virtue so common to the dreams and reveries of youth—it is extremely difficult to ascertain. Some of his biographers are of opinion that the lady whom he has celebrated in his works under the name of Bice, or Beatrice, was the daughter of Folco Portinari, a noble Florentine; while others contend that she is merely a personification of wisdom or moral philosophy. But Dante’s own account of his love is given in terms often so enigmatical and apparently contradictory, that it is almost impossible to make them agree perfectly with either of these suppositions.

Whatever its object, his affection seems to have been most chaste and spiritual in its nature. Instead of alienating him from literary pursuits, it increased his thirst after knowledge, and ennobled and purified his feelings. With the aid of this powerful incentive, he soon distinguished himself above the youth of his native city, not only by his acquirements, but also by elegance of manners, and amenity of temper. Thus occupied by his studies, refined and exalted by his love, and cherished by his countrymen, the morning of his life was sunned by the unclouded smiles of fortune, as if to render darker by the contrast the long and gloomy evening which awaited him.

His pilgrimage on earth was cast in one of the most stormy periods recorded in history. The Church and the Empire had been long engaged in a scandalous contest, and had often involved a great part of Europe in their quarrels. Italy was especially distracted by two contending parties, the Guelfs, who adhered to the Pope, and the Ghibelines, who espoused the cause of the Emperor. In the year 1266, after a long alternation of ruinous reverses and ferocious triumphs, the Guelfs of Florence drove the Ghibelines out of their city, and at last permanently established themselves in power. The family of Dante belonged to the victorious party; and while he remained in Florence, it would have been dangerous, perhaps impossible, to avoid mingling in these civil broils. He accordingly went out against the Ghibelines of Arezzo in 1289; and in the following year against those of Pisa. In the former campaign he took part in the battle of Campaldino, in which, after a long and doubtful conflict, the Aretines were completely defeated. On that memorable day he fought valiantly in the front line of the Guelf cavalry, manifesting the same energy in warfare, which he had displayed in his studies and in his love.

But soon after the tumults of the camp had interfered with the calm of his private and meditative life, his adored Beatrice, whether an earthly mistress, or an abstraction of his moral and literary studies, was torn from him. This loss, which in his writings he never ceases to lament, reduced him to extreme despondency. Nevertheless in 1291, but a few months after it, he married a lady of the noble family of the Donati, by whom he had numerous offspring; a circumstance which would indicate a strange inconsistency of character, had his heart been really preoccupied by another love. This connexion with one of the first families of the republic may have smoothed his way to civic eminence; but if Boccaccio, usually a slanderer of the fair sex, be credited, the lady’s temper proved unfavourable to domestic comfort.

He now entirely devoted himself to the business of government, and attained such reputation as a statesman, that hardly any transaction of importance took place without his advice. It has even been asserted that he was employed in no less than fourteen embassies to foreign courts. There may be some exaggeration in this statement; but it is certain that in 1300, at the early age of five and thirty, he was elected one of the Priors, or chief magistrates of the republic; a mark of popular favour which ended in his total ruin.

Читать дальше