The ‘Liber Albus’ contains other ordinances against brawlers and loose livers. The former, whether male or female, were taken to the thew, a form of pillory, carrying a distaff dressed with flax and preceded by minstrels. The latter, whether male, female, or clerics, were marched behind music to Newgate, and into the Tun in Cornhill.[12] Repeated offences were visited with expulsion, and the culprits were compelled to forswear the city for ever. The men on exposure had their heads and beards shaved, except a fringe on their heads two inches in breadth; women who made the penance in a hood of “rag” or striped cloth had their hair cut round about their heads. Worse cases of both sexes were shaved like “an appealer,” or false informer. The crime of riotous assembling was very sharply dealt with, as appears from the proclamation made in the King’s (Edward III.) departure for France. It was then ordained that “no one of the city, of whatsoever condition he shall be, shall go out of the city to maintain parties, such as taking leisure, or holding days of love (days of reconciliation between persons at variance), or making other congregations within the city or without in disturbance of the peace of our lord the king, or in affray of the people, and to the scandal of the city.” Any found guilty thereof were to be taken and put into the prison of Newgate, and there retained for a year and day; and if he was a freeman of the city, he lost his freedom for ever.

The city authorities appear to have been very jealous of their good name, and to have readily availed themselves of Newgate as a place of punishment for any who impugned it. A certain John de Hakford, about the middle of the fourteenth century, was charged with perjury in falsely accusing the chief men in the city of conspiracy. For this he was, presumably upon proof, remanded by the Mayor and aldermen to Newgate, there to remain until they shall be better advised as to their judgment. A little later on, Saturday the morrow of St. Nicholas (6 Dec., 1364), this judgment was delivered, to the effect that the said John shall remain in prison for one whole year and a day, and the said John within such year shall four times have the punishment of the pillory, that is to say, one day in each quarter of the year, beginning on the Saturday aforesaid, and in this manner: “The said John shall come out of Newgate without hood or girdle, barefoot and unshod, with a whetstone hung by a chain from his neck and lying on his breast, it being marked with the words ‘a false liar,’ and there shall be a pair of trumpets trumpeting before him in his way to the pillory, and there the cause of this punishment shall be solemnly proclaimed, and the said John shall remain in the pillory for three hours of the day, and from thence shall be taken back to Newgate in the same manner, there to remain until his punishment be completed in manner aforesaid.” This investiture of the whetstone was commonly used as a punishment for misstatement;[13] for it is recorded in 1371 that one Nicholas Mollere, servant of John Toppesfield, smith, had the punishment of the pillory and whetstone for “circulating lies,” amongst others that the prisoners at Newgate were to be taken to the Tower of London, and that there was to be no longer a prison at Newgate.

Again in 1383, William Berham for slandering the Mayor was adjudged to be put upon the pillory on the same day, there to stand for one hour of the day with one large whetstone hung from his neck in token of the lie he told against the Mayor, and another smaller whetstone in token of a lie told against a lesser personage. After that he was to be taken back to Newgate, and thence for the five following days

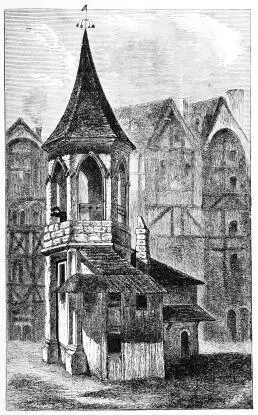

ANCIENT PILLORY IN PARIS.

to be taken to the pillory, before noon on one day and after noon on the next, and there exposed with the whetstone as before. A few years later one Robert Stafferstone for slandering an alderman was adjudged to be imprisoned in Newgate for the next forty days, “unless he should find increased favour.” This favour he did subsequently find, and “upon his humiliation he was committed to prison until the morrow, namely, Palm Sunday, and on the same Sunday should be taken from the prison to his house, and from thence proceed between the eighth and ninth hour, before dinner, with his head uncovered, and attended by an officer of the city, carrying a lighted wax candle weighing two pounds through Walbrook Bokelersbury, and so by Conduit and Chepe to St. Lawrence Lane in the Old Jewry, and on to the chapel of the Guildhall, where he was to make offering of the candle. That done, all further imprisonment was to be remitted and forgiven.”

A sharper sentence was meted out about the same date to William Hughlot, who for a murderous assault upon an alderman was sentenced to lose his hand, and precept was given to the sheriffs of London to do execution of the judgment aforesaid. Upon this an axe was brought into court by an officer of sheriffs, and the hand of the said William was laid upon the block there to be cut off. Whereupon John Rove (the alderman aggrieved), in reverence of our lord the king, and at the request of divers lords, who entreated for the said William, begged of the Mayor and aldermen that the judgment might be remitted, which was granted accordingly. The culprit was, however, punished by imprisonment, with exposure on the pillory, wearing a whetstone, and he was also ordered to carry a lighted wax candle weighing three pounds through Chepe and Fleet Streets to St. Dunstan’s church, where he was to make offering of the same.

But, however sensitive of their good name, the Mayor and aldermen of those times seem to have been fairly upright in their administration of the law. The following case shows this. A man named Hugh De Beone, arraigned before the city coroner and sheriff for the death of his wife, stood mute, and refused to plead, so as to save his goods after sentence. For thus “refusing his law of England,” the justiciary of our lord the king for the delivery of the gaol of Newgate, committed him back to prison, “there in penance to remain until he should be dead.”[14]

The punishment inflicted, the goods thus saved were handed over to the defunct criminal’s executor as appears from the following. “Be it remembered that on Saturday next before the Feast of the Apostles Simon and Jude (28 October), in the eleventh year of King Edward, after the conquest, the third, came John Fox, citizen and vintner of London, before Gregory de Nortone, Recorder, and Thomas de Margus, chamberlain of the Guildhall of London, into the chamber of the Guildhall aforesaid, and acknowledged that he had received of Walter de Moedone and Ralph de Uptone, late sheriffs of London, the goods and chattels underwritten in the presence of John de Shirborne, coroner, and the Sheriff of London aforesaid, on the oath of Edward de Mohaut, pellifer,[15] and others.” The inventory of goods is curious, and is perhaps worth quoting at length. There were—

One mattress, value 4 s. ; six blankets and one serge, 13 s. 6 d. ; one green carpet, 20 s. ; one torn coverlet, with shields of cendale, 4 s. ; one coat, and one surcoat, of worstede , 40 d. ; one robe perset, furred, 20 s. ; one robe of medly, furred, one mask, one old fur, almost consumed by moths, 6 d. ; one robe of scarlet, furred, 16 s. ; one robe of perset, 7 s. ; one surcoat, with a hood of ray, 2 s. 6 d. ; one coat, with a hood of perset, 1 s. 6 d. ; one surcoat, and one coat of ray, 6 s. 1 d. ; one green hood of cendale, with edging, 6 d. ; seven linen sheets, 5 s. ; one table-cloth, 2 s. ; three table-cloths, 1 s. 6 d. ; and a great many other articles, including “brass pots,” “aundirons,” “tonour,” “iron herce,” “savenapes,” bringing the total value to £12 18 s. 4 d.

Читать дальше