In some cases where goats are prohibited by a city or other municipality, people with special needs or medical issues have been able to obtain variances to the zoning so that a goat could serve as a service or therapy animal.

If your city does not allow backyard goats, you’ll need to work with the powers that be to get the law revised, like other urban farmers are doing in cities around the United States. Grant suggests putting together a petition and obtaining signatures and then taking it to the city council and requesting a hearing. If you also obtain email addresses on the petition, you’ll have a ready-made list to notify interested parties when the hearing is scheduled.

If your city does not allow backyard goats, you’ll need to work with the powers that be to get the law revised, like other urban farmers are doing in cities around the United States. Grant suggests putting together a petition and obtaining signatures and then taking it to the city council and requesting a hearing. If you also obtain email addresses on the petition, you’ll have a ready-made list to notify interested parties when the hearing is scheduled.

Also helpful are recommendations on what should be covered by such an ordinance, such as miniature goats only, a limitation on the number, only does or wethers, and whether they need to be licensed. You can use another city ordinance as a pattern for the one you’re proposing.

Even more important is to know your neighbors. Do they have any vicious or out-of-control dogs that may be a threat to your goats? Can you keep these dogs away from your goats?

Do you already have bad blood with neighbors? Will they bitterly complain, undermine you, or otherwise make your life miserable if they hear goat cries? If you live in an area where you’ll need a livestock guardian dog, will neighbors have a problem with nighttime barking? Try to work things out first, but if you can’t, think about whether you want to invest a lot of time, money, and heart in a project where a nearby neighbor will make your life difficult.

After you get goats, share some of your goat products with your neighbors, consider involving them or their children in your project, and work with them to make sure your goats aren’t causing a problem.

After you get goats, share some of your goat products with your neighbors, consider involving them or their children in your project, and work with them to make sure your goats aren’t causing a problem.

Better yet, if they’re interested, teach your neighbors about goats. You could even offer to work with a neighbor child who is interested in raising goats for 4-H. If you have neighbors who have enough interest, they may be willing to learn enough to be able to care for them so you can take a vacation. It’s a win-win!

Chapter 2

Glimpsing Vital Goat Statistics

IN THIS CHAPTER

Using the correct terminology for goats

Using the correct terminology for goats

Focusing on features that make a goat a goat

Focusing on features that make a goat a goat

Identifying a healthy goat

Identifying a healthy goat

Goats are interesting and amazing animals. They’re related to sheep, deer, and cattle but have some basic differences. Talking about goats and their various parts requires you to pick up some new vocabulary.

In this chapter, I give you an introduction to goat terminology, take you through body parts that are integral to “goatness,” and give you some tips on what to expect from a healthy goat and how to tell whether things are starting to go wrong.

Doe, a Goat, a Female Goat

If you want to get goats, you need to talk goats with other goat lovers. To help you avoid missteps, here is the basic terminology that you need to ask questions and talk about goats knowledgeably:

Doe: A female goat. A young doe is called a doeling. You may have heard a female goat called a nanny. But don’t use that term unless you want to offend someone. Some meat goat owners still call their does nannies, but the more common term these days is doe, especially if you’re getting dairy goats.

Buck: A male goat. A young buck is called a buckling. Like nanny goat, billy is also considered a negative term for a male goat, bringing to mind a scruffy, stinking animal. Some meat goat owners still use this term, but in order not to offend, use buck instead.

Brood doe: A doe that is kept and used for breeding purposes, to pass on certain desirable genetic traits.

Kid: A baby goat or a goat less than a year old.

Yearling: A goat that is between one and two years old.

Wether: A castrated male goat.

Herd: A group of goats. Sheep are in flocks; goats are in herds.

Ruminant: An animal that has a stomach with four compartments and chews cud as part of the digestive process. Goats are ruminants.

Udder: The organ in a goat that produces milk. Don’t call it a bag. Goats have only one udder.

Teat: The protuberance from the udder that you use to milk a goat. Goats have two teats.

Dam: A goat’s mother.

Sire: A goat’s father. You can also say that a goat sired a kid.

Taking a Look at Goat Anatomy

Goats are mammals and are similar to other mammals in some ways. But they also have unique features that indicate whether they are healthy, tell you how old they are, and even give clues about their parents.

In this section, I tell you about different parts of the goat, how to tell a goat’s age by his teeth, and how to tell a goat from a sheep. (Some of them do look similar.)

You can own goats and not know the names of parts of the body. But if you want to have an intelligent discussion with other goat aficionados or show your goats, knowing the correct terminology is essential.

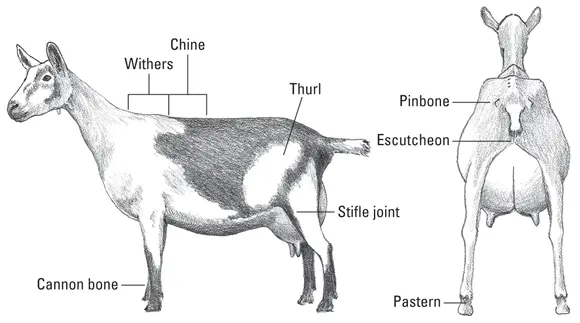

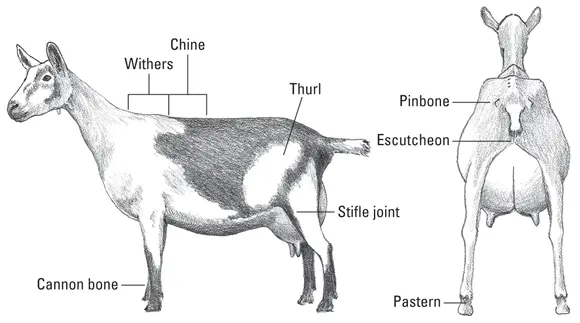

Figure 2-1 shows you the names of the different parts of a goat. Some are obvious — we all can identify an ear or a neck. But others may be new to you if you haven’t raised animals before. Here are some terms for different body parts:

Cannon bone: The shin bone.

Chine: The area of the spine directly behind the withers.

Escutcheon: The area between the back legs, where the udder lies in a doe. This area should be wide in a dairy goat.

Pastern: The flexible part of the lower leg below the dewclaw and above the hoof.

Pinbone: The hip bone.

Stifle joint: In the back leg, the equivalent of the knee in a goat.

Thurl: The hip joint, usually referred to in relation to the levelness between the thurls.

Withers: The shoulder area or area of the spine where the shoulder blades meet at the base of the neck. You measure from this point to the ground to determine a goat’s height.

FIGURE 2-1:The parts of a goat’s body.

Goats are ruminants, which means that they have four stomach compartments and part of their digestive process includes regurgitating partially digested food and chewing it, called ruminating. This kind of digestive system needs a plant-based diet.

Understanding a goat’s digestive system and how it works helps you keep your herd healthy or identify potential problems.

The goat stomach consists of three forestomachs — the rumen, reticulum, and omasum — and a true stomach, the abomasum. (See Figure 2-2.) The forestomachs are responsible for grinding and digesting hay, with the help of bacteria. The last compartment, the abomasum, is similar to the human stomach and digests most proteins, fats, and carbohydrates.

The goat stomach consists of three forestomachs — the rumen, reticulum, and omasum — and a true stomach, the abomasum. (See Figure 2-2.) The forestomachs are responsible for grinding and digesting hay, with the help of bacteria. The last compartment, the abomasum, is similar to the human stomach and digests most proteins, fats, and carbohydrates.

Читать дальше

If your city does not allow backyard goats, you’ll need to work with the powers that be to get the law revised, like other urban farmers are doing in cities around the United States. Grant suggests putting together a petition and obtaining signatures and then taking it to the city council and requesting a hearing. If you also obtain email addresses on the petition, you’ll have a ready-made list to notify interested parties when the hearing is scheduled.

If your city does not allow backyard goats, you’ll need to work with the powers that be to get the law revised, like other urban farmers are doing in cities around the United States. Grant suggests putting together a petition and obtaining signatures and then taking it to the city council and requesting a hearing. If you also obtain email addresses on the petition, you’ll have a ready-made list to notify interested parties when the hearing is scheduled. Using the correct terminology for goats

Using the correct terminology for goats

The goat stomach consists of three forestomachs — the rumen, reticulum, and omasum — and a true stomach, the abomasum. (See Figure 2-2.) The forestomachs are responsible for grinding and digesting hay, with the help of bacteria. The last compartment, the abomasum, is similar to the human stomach and digests most proteins, fats, and carbohydrates.

The goat stomach consists of three forestomachs — the rumen, reticulum, and omasum — and a true stomach, the abomasum. (See Figure 2-2.) The forestomachs are responsible for grinding and digesting hay, with the help of bacteria. The last compartment, the abomasum, is similar to the human stomach and digests most proteins, fats, and carbohydrates.