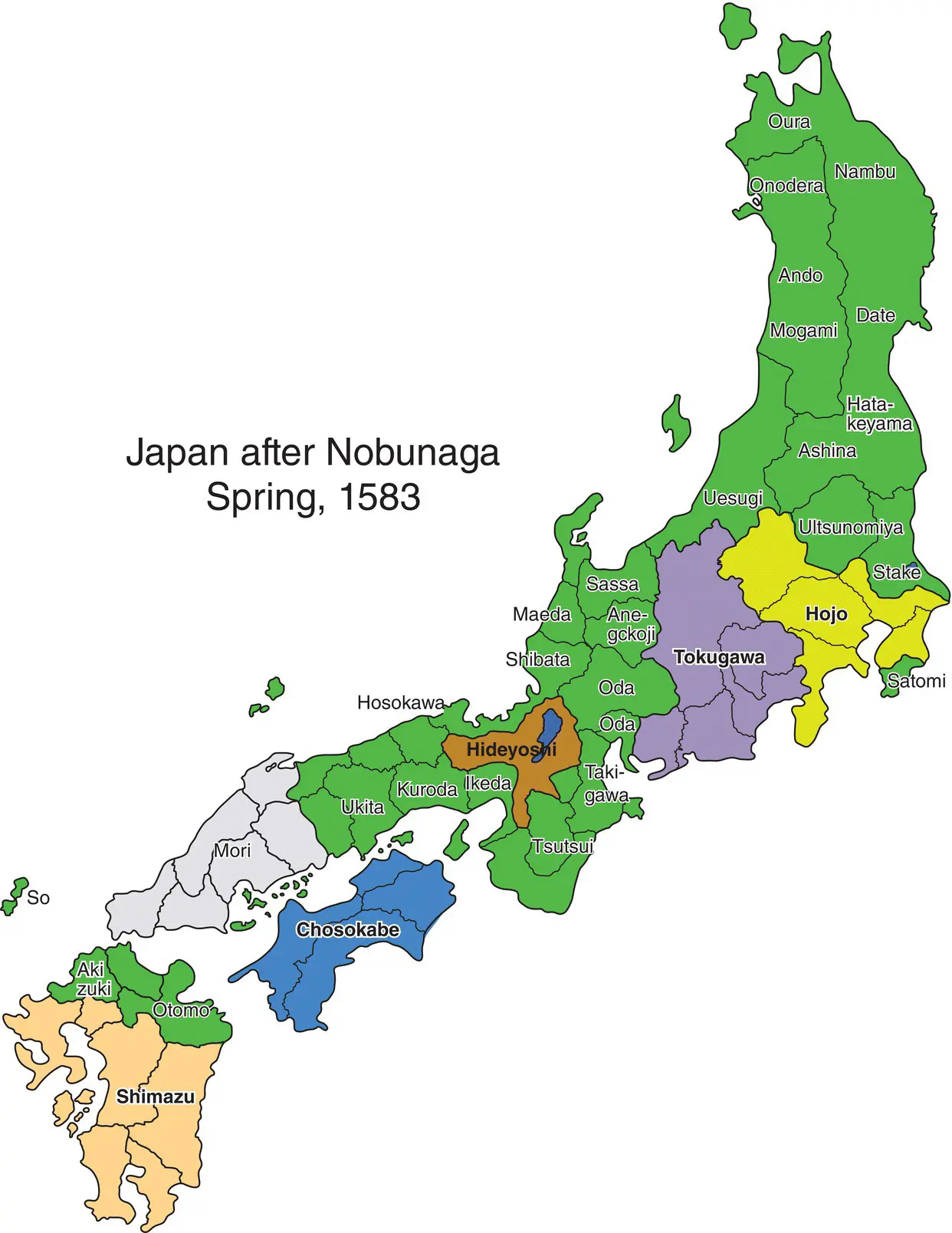

When Hideyoshi died, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) became regent to his infant son, but he seized the reins of power and became shogun instead. He relocated his bakufu from Kamakura down the road to Edo (modern Tokyo), and further strengthened and centralized the government bureaucracy. His restructured government worked so well that he was able to complete Japan’s unification, end the slaughter and destruction of endless civil wars, and create two and a half centuries of peace, stability, and economic growth. His Tokugawa Shogunate was the last and greatest of the shogunates.

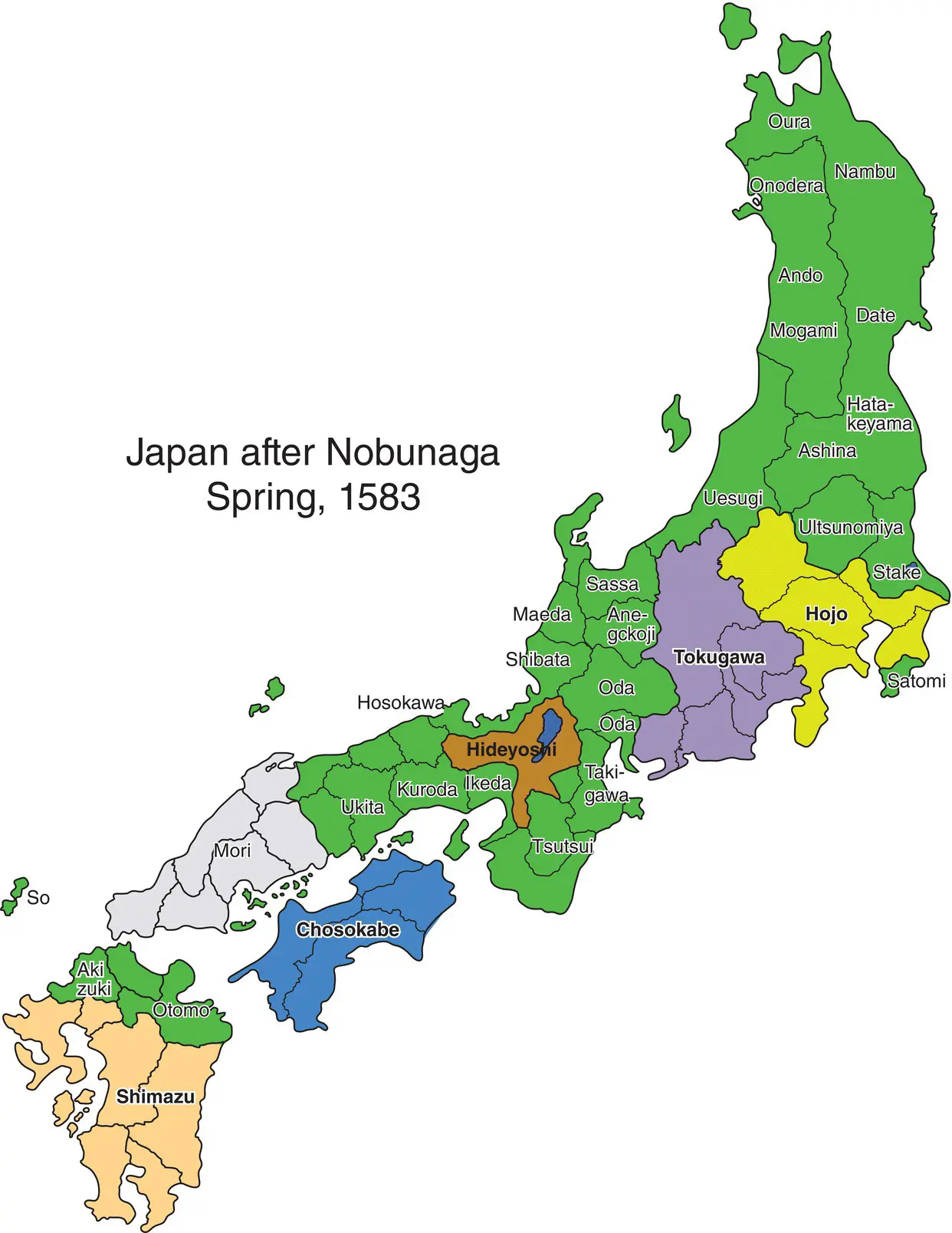

Map of Japan during and after Oda Nobunaga’s reign.

Source: From https://www.samurai‐archives.com/image/1583.gif. Reproduced with permission of C.E. West and F.W. Seal.

The Tokugawa shoguns adopted many measures to consolidate their power. One measure was the Alternate Residence System. The shoguns required the local lords to spend alternate years in residence in Edo, to leave their favorite wives and sons behind as hostages when they returned to their domains, and to spend lavishly on maintaining elaborate residences both in the capital and at home. This system gave the shogun the institutional apparatus to hit two birds with one stone: It enabled him to exercise physical control over the person of the local lords even as he emptied their coffers. The shoguns also frequently called on the local lords to “make loans” to the government to support such public projects as waterworks, and it was understood that these “loans” would never be paid back. The shoguns quickly built up their strength and filled up their coffers at the expense of the local lords. It wasn’t long before the local lords found themselves still in possession of their domains, but no longer enjoying autonomy. The Tokugawa shoguns had created a centralized feudal state.

Although Tokugawa Ieyasu came from peasant stock, he enforced a policy of freezing class lines and creating a system that was nearly a caste system. The royal family was set apart and above all other classes. The rest of society was divided into four classes: the samurai, the peasants, the artisans, and the merchants, in descending order. This Japanese social structure was a modification of the Chinese model, in which the Japanese samurai warrior class replaced the Chinese scholar‐official class.

The Tokugawa shoguns had little use for the military prowess of the samurai warriors in a unified country where peace reigned. But they did face a new demand for a large number of civil administrators to run their elaborate government bureaucracy. Under these new circumstances, the samurai class of sword‐wielding warriors morphed into a class of pen‐pushing bureaucrats. But to make the transition, they had to go through the crucible of studying the Confucian classics, for it would teach them the essential skills of a bureaucrat—reading and writing—and instill in them a strong sense of loyalty to the emperor (and, by extension, to the shogun).

The warrior‐turned‐bureaucrat samurai were given the privilege of being the only men permitted to staff the state bureaucracy as civil officials. But the privilege came at a price: They were required to reside in the castle‐towns and give up their right to own land in exchange for a fixed stipend. They were also banned from switching masters, which had been a common cause of social instability. Thus, the once‐proud class of warriors was turned into a class of salaried administrators sitting in government offices.

Peasants were confined to living on the land and cultivating crops in the countryside. They were banned from owning weapons. Merchants were officially relegated to the bottom of society as the fourth class. A near‐frozen caste‐like system was now in place.

The Tokugawa policies produced the unintended consequence of a commercial revolution. First, they created a stable and peaceful environment that was inductive to economic and population growth. Second, the local lords had to sell the harvests from their land in order to acquire cash to purchase goods and services they needed in the capital and their castle‐towns, and this created a sharp increase in the demand for trade and cash. Osaka became the commercial center of Japan, especially of its rice trade. The commercialization of Japan’s economy turned the country into a money society.

The lords and samurai were inept at managing money, and the lowly merchants were soon the money managers of their social superiors. When inflation hit, however, the samurai with their fixed stipends became impoverished, and were often reduced to being debtors to the merchants who were managing their money. The officially high status of the samurai class and the officially low status of the merchant class were no longer reflective of reality. In fact, the reverse was true: Merchants had become a wealthy and influential class, while the samurai’s status was badly diminished. In most cases, a town’s economy was controlled by big merchant families who enjoyed special privileges granted to them by the government.

The Tokugawa government’s main source of revenue came from tax farming, and it levied these taxes on a village as an entity, rather than on the individual land owners or cultivators. The government had a hands‐off policy as long as a village paid its taxes. This autonomy allowed the villages to manage their own business, and agricultural production surged. A vigorous economy promoted the division of labor. “Big houses” in a village would go into the manufacture of silk and sake, or operate pawn shops. “Head men” from the “big houses” would develop leadership qualities. The villages in Tokugawa Japan grew into solid social entities.

Japan’s traditional merchants enjoyed many privileges under Tokugawa rule. They had great vested interests in the existing order, and therefore had no incentive to be agents of change. As traditional Japan moved toward modernization, the traditional merchant class would fade into obscurity. This trait distinguishes the traditional Japanese merchant from its counterpart in Europe and America, where the merchant class was a driving force for change and revolution.

Tokugawa stability was not stagnation. Rather, it was a time when Japan created a sophisticated national government staffed with educated and disciplined samurai, developed a prosperous money economy, cultivated a strong and productive agricultural population, and wove a strong social fabric. Tokugawa Japan was creating the building blocks of a modern Japan. In Japan’s drive toward modernization, the samurai‐turned‐administrators would quickly assume leadership roles in civil government, the military, and business; the village “headmen” would become grassroots leaders of a modern Japanese state; and the villages would provide the initial capital for its early industrialization.

Premodern Korea

Ancient Korea: The Land and the People

The Korean Peninsula is about 600 miles long and 125–200 miles wide. It borders with China and Russia to the north, and its southernmost shore is less than 120 miles from Japan across the ocean. A massive mountain range runs along its eastern coastline, leaving most of its plains and valleys to the west and south. Only 14% of its territory is fit for cultivation.

The ancestors of modern‐day Koreans were migrants from Siberia and Manchuria who settled on the Korean Peninsula. Ethnically, the Koreans and the Japanese share a common origin with the indigenous people of Siberia and Manchuria. Linguistically, they both speak an Altaic language, which is unrelated to Han Chinese. Early Koreans were a tribal people who relied on fishing, hunting, and gathering for subsistence. As agriculture grew, they built villages and towns. Chinese know‐how, from early crop growing and animal husbandry to later metallurgy, flowed from China to Korea, and enabled Korean civilization to advance at a much faster pace than what was normal for other civilizations. This cultural influence was then relayed to Japan. The Koreans also adopted the Chinese writing system (Han Chinese characters), Confucianism, and China’s centralized bureaucratic structure of government. Korea is part of the cultural sphere of Confucianism, along with China, Japan, and Vietnam.

Читать дальше