The available information, however, permits us to conclude that the population was divided into defined groups and classes. The king and the royal family were at the apex, with the monarch performing ritual functions (including divination), commanding military forces, and amassing considerable quantities of grain, craft articles, and other valuables. The lords to whom the king entrusted land for the construction of new settlements held sway over these territories, as well as over the inhabitants. They too received substantial amounts of the goods produced within their domains. Less privileged were the peasants, slaves, craftsmen, and merchants. Peasants did not own the land they farmed and turned over much of the produce to the king and the lords. Known as zhongren (multitude), they could be conscripted into the military or for labor service. Often captives of war, slaves could count themselves fortunate if they were employed to farm the land or to act as servants and unfortunate if they were selected to be sacrificial victims. Although craftsmen had a higher status and lived better than the zhongren and the slaves, the articles they fashioned were most often designed for the king and the nobility.

This generally stable social structure contributed to a popularly accepted conception of the uniqueness of Shang culture. Some archeologists asserted that its culture and artifacts were primarily indigenous. Even more significant was that the inhabitants of the Shang perceived themselves as a different people. They had, after all, developed a sophisticated culture, with a worked-out political system, a highly organized bronze industry, a unique burial system, and a written language. Their pictorially based written language, found mostly on the oracle bones and perhaps in some signs and symbols on ceramics, contributed, in large measure, to the Shang people’s feelings of identity. The language, with its initial associations with divination and religion, proved a powerful vehicle for the fostering of their sense of affinity.

With the growth of such feelings of identity, the Shang distinguished itself from other neighboring regions, which were sometimes adversaries. Most attacks against Shang territory originated from its north and northwest, and the final onslaught, which overwhelmed the dynasty and permitted the rival Zhou dynasty to take power, derived from the northwest. Competition for land and for control of mineral deposits and other natural resources provoked crises and conflicts between the Shang and nearby territories. Such hostilities bedeviled relations between these various states.

1 1 K. C. Chang, The Archaeology of Ancient China (New Haven: Yale University Press, 4th ed., 1986), p. 310.

1 E. J. W. Barber, The Mummies of Ürümchi (New York: W. W. Norton, 1999).

2 Roderick Campbell, Violence, Kinship and the Early Chinese State: The Shang and Their World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

3 Kwang-chih Chang, Shang Civilization (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980).

4 Kwang-chih Chang, The Archaeology of Ancient China (New Haven: Yale University Press, 4th ed., 1986).

5 Li Feng, Early China: A Social and Cultural History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

6 David Keightley, Sources of Shang China: The Oracle Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985).

7 Harry Shapiro, Peking Man (London: Allen & Unwin, 1974).

8 Gideon Shelach-Lavi, The Archaeology of Early China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[2] CLASSICAL CHINA, 1027–256 BCE

“Feudalism”?

Changes in Social Structure

Political Instability in the Eastern Zhou

Transformations in the Economy

Hundred Schools of Thought

Daoism

Popular Religions

Confucianism

Mohism

Legalism

Book of Odes and Book of Documents

Secularization of Arts

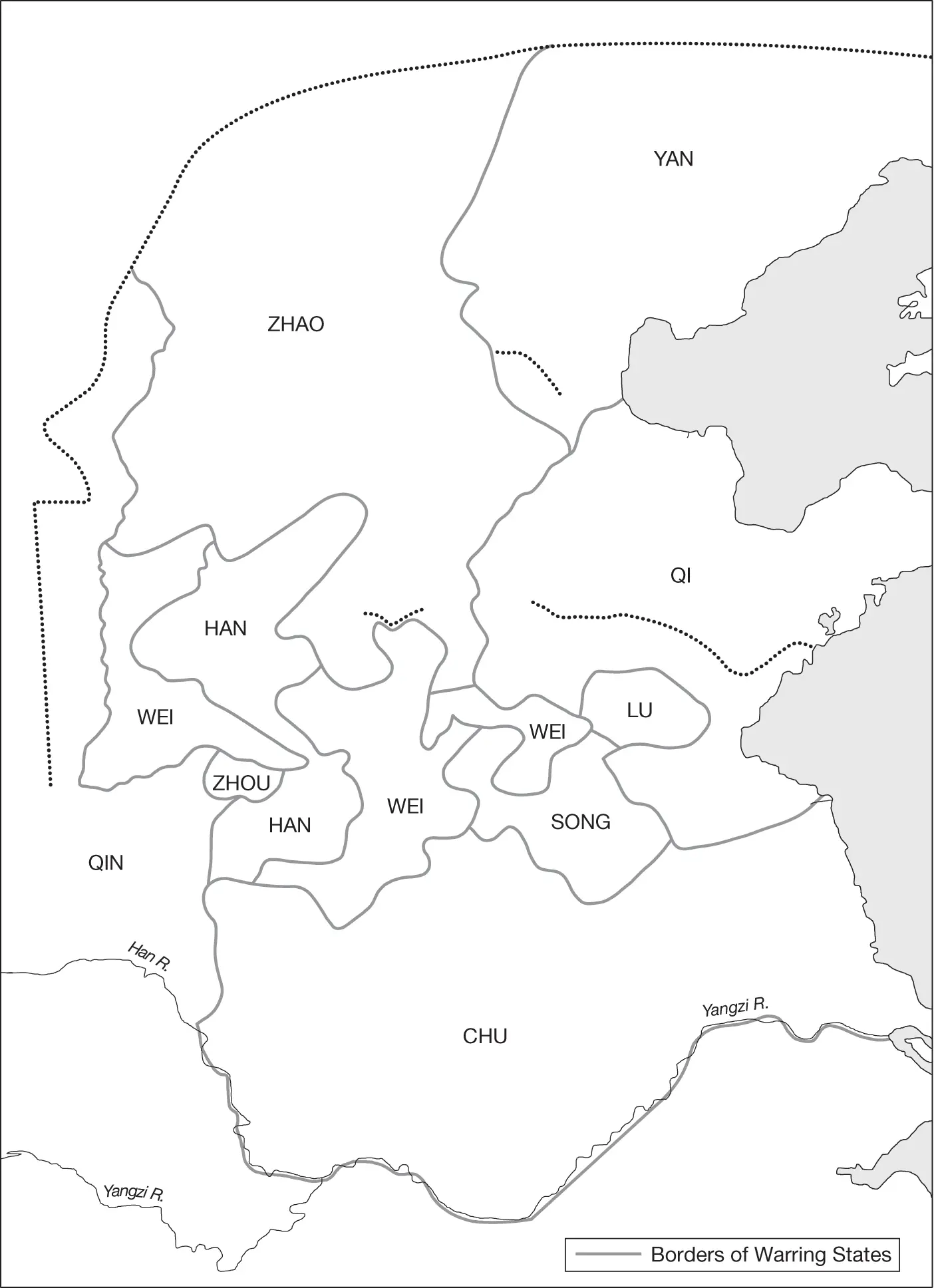

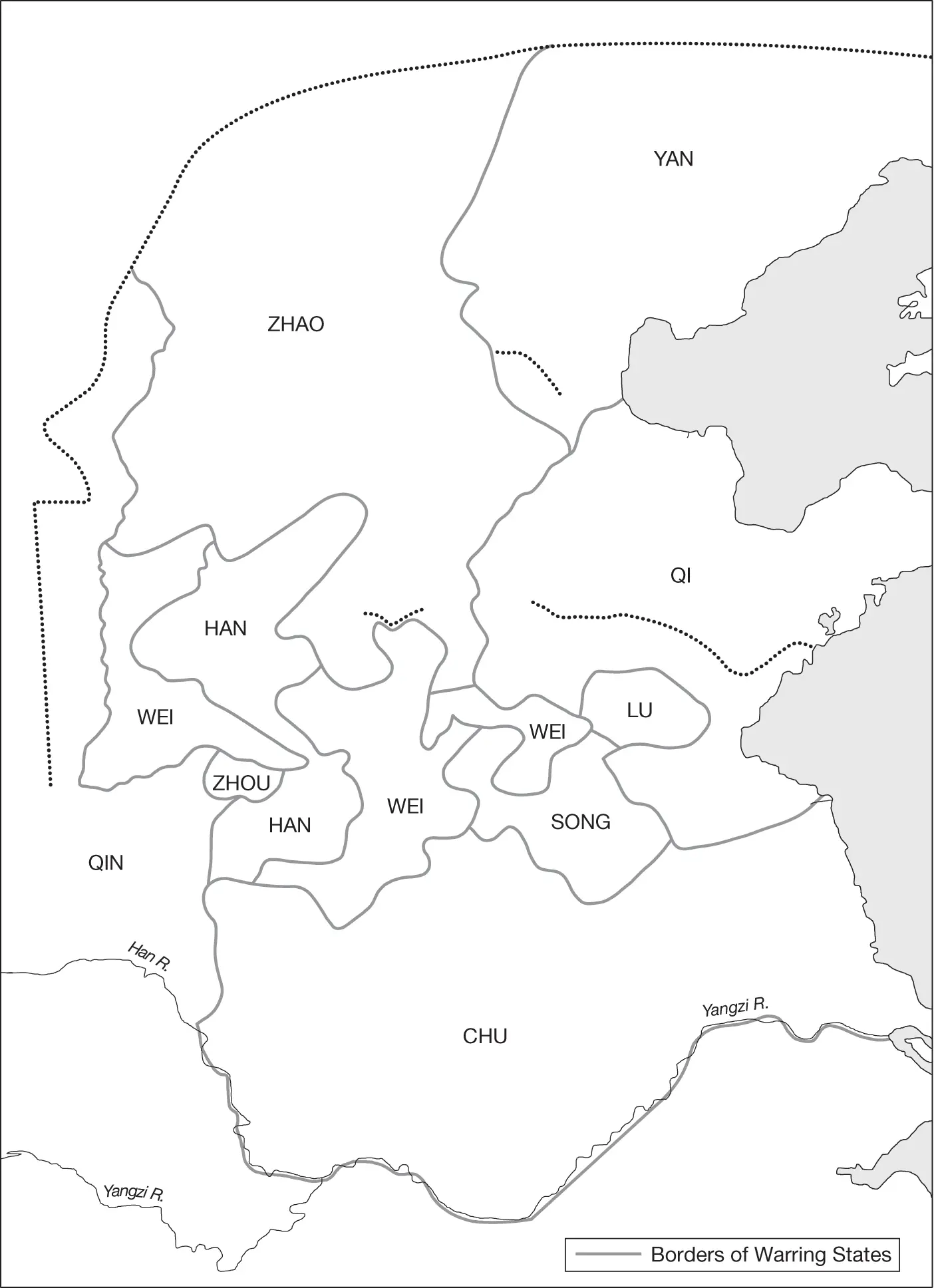

Although the Zhou lasted longer than any other dynasty in Chinese history, its longevity may be deceptive. There was a sharp break in the dynasty, for in 771 BCE it was compelled to move its capital. During the first phase, known as the Western Zhou, its administrative center was located in the Wei river valley, west of the modern city of Xian; in the succeeding phase, known as the Eastern Zhou, the capital was transferred to Chengzhou (near the present-day location of Luoyang), which the Western Zhou had used as a secondary capital. The remaining five centuries of Eastern Zhou rule witnessed a rapid deterioration in its ability to govern, leading to a chaotic struggle for power between areas reputedly under its jurisdiction during the so-called Warring States period (403–221 BCE).

Map 2.1Warring States-era divisions.

The Zhou had from its inception set up a decentralized government, which some scholars identify as similar to the European system of feudalism. However, the concept of European feudalism is also murky. In its simplest form, it consisted of a legal and military system based on a relationship between a lord and a vassal. A lord who owned land turned over possession of a portion of that land (known as a fief) to a vassal in return, principally, for military services. Their mutual obligations and rights entailed a pledge of loyalty to the lord by the vassal and a pledge of protection of the vassal by the lord. Peasants who worked the land on manors for the lords and vassals or in Church estates were also part of this feudal society. Yet there were so many variations of “feudalism” in Europe that some scholars have stopped using the term in relation to China. Thus, the Western Zhou may be best described as a society in which the local nobility often supplanted the kings as true wielders of power. The rudimentary levels of transport, communications, and technology clearly reduced the opportunities for centralization. Even so, the Zhou political system, particularly the Eastern Zhou, tilted further toward localism than such limitations would have mandated.

Decentralization stemmed from the initial Zhou conquests, though it should be noted that disentangling myth from reality concerning its early years is difficult. Part of the problem is that texts allegedly written in the Zhou actually derive from later periods. Many Chinese accepted the earlier dates. The sources all concur that the Zhou peoples traced their ancestry to Hou Ji, whose second name translates as “millet.” This semidivine figure reputedly instructed his descendants in the basics of farming. Inhabiting as it did the areas west of the Shang kingdom in the Wei river valley, the Zhou often had bellicose relations with its neighbor for several generations before their final confrontation in the eleventh century BCE. Despite these conflicts, the Zhou was influenced by the Shang. Designs and techniques of early Zhou bronzes and ceramics resembled Shang prototypes, and their rituals were often similar.

Culmination of the strained relationship occurred during the reigns of the stereotyped, almost legendary father-and-son monarchs, Wen and Wu of Zhou. The sources endow Wen (his name signifying “accomplished” or “learned”) with the attributes of a sage-ruler. Intelligent and benevolent, Wen believed in negotiations and compromise in relations with others and in governing his own people. His remarkable character paved the way for his son Wu (his name meaning “martial’) to battle with and overwhelm the Shang. The sources praise Wu for his military successes, but Wen represented the ideal. Even at this early stage in Chinese culture, civil virtues were more highly prized than military skills. The sources, for example, extol the Zhou for their magnanimity toward their defeated enemies. Instead of adopting a military solution and extirpating the Shang royal family, the leaders of Zhou gave them land in order to permit them to continue their ancestral rituals.

Читать дальше