The diverse shapes of the vessels, some of which derive from shapes of Neolithic pottery, and their decorations reveal the skill of the bronze craftsmen. Art historians have identified at least five stages of decoration, with each evincing a more elaborate style and more detailed decoration of the objects. The origins of the decorations and indeed of the high level of bronze casting are unknown, but the quality and the large number of bronzes indicate the presence of a sizable industry and skilled artisans. The artisans were favored in this social structure; for example, they lived in houses with floors of stamped earth rather than in the virtually underground residences of ordinary folk.

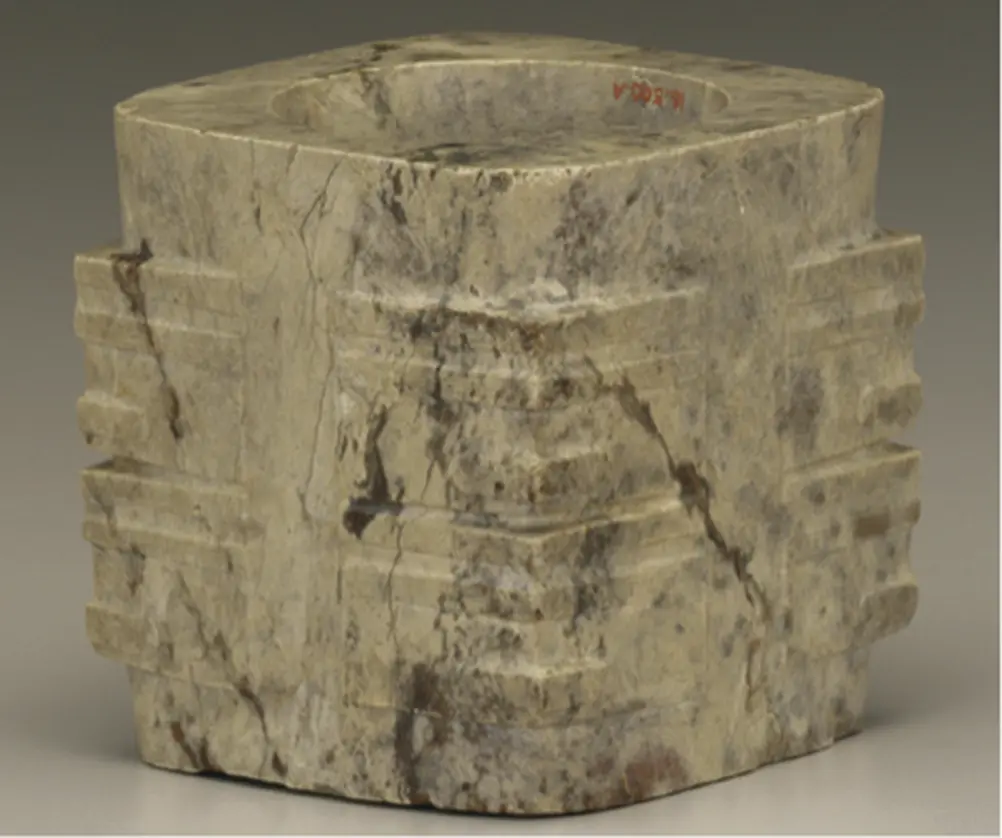

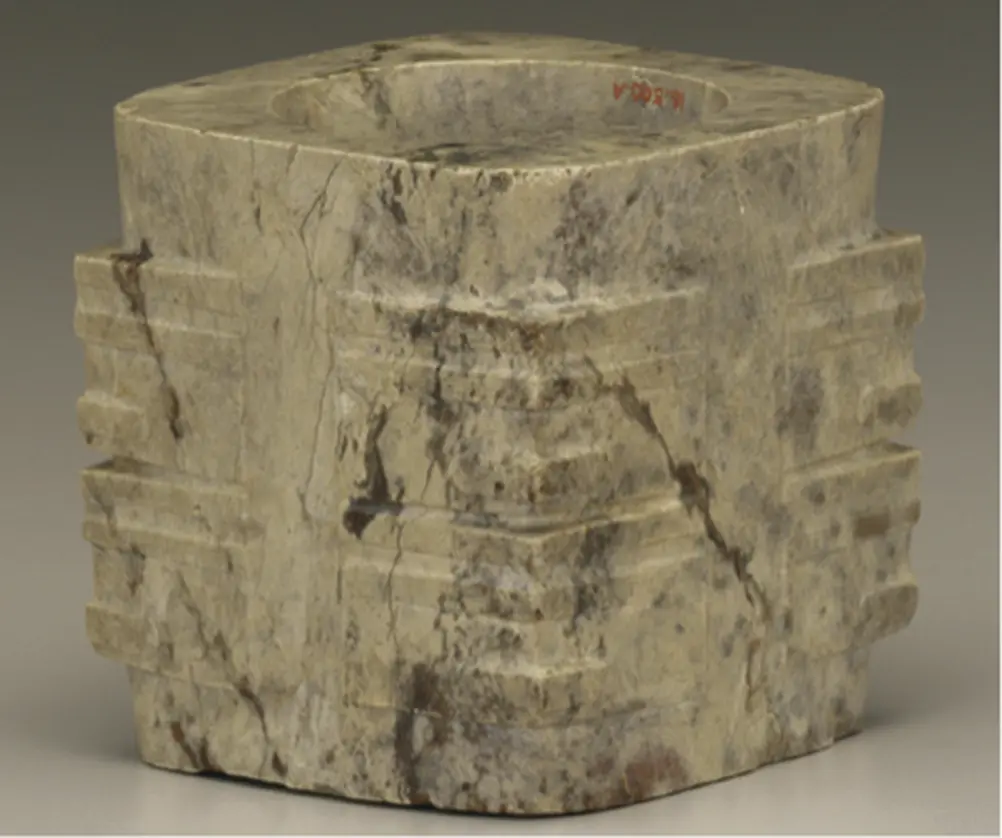

Along with a sophisticated bronze industry, the Shang also produced jade, ceramic, and lacquer objects. Jade carving developed in the Neolithic, but more jade artifacts have survived from the Shang. Jade knives, weapons, and jewelry, often with incised decorations of animals or simple geometric designs, have been found in many burial sites. Their appearance at burial sites may indicate that they had a ritual or religious significance. They may, for example, have served as offerings to the spirits or the ancestors. The bi ring, a disc in the shape of a circle, probably had such ceremonial associations and may have been used in divining the future. Some of the jade probably came from outside the core area of Shang culture, testifying to the development of commerce during this era. Lacquerware has also been discovered in some Shang tombs. Like the motifs on jade and ceramics, the designs on lacquer reveal an interest in the depiction of animals.

Figure 1.5 Cong (jade tube), Neolithic culture, 3300–2250 BCE. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA/Gift of Charles Lang Freer/The Bridgeman Art Library.

The Shang’s more populous settlements, larger towns, elaborate and grander tombs, bronze industry, and ceramics and jade production, as well as the greater emphasis accorded to divination, presume a more organized society, an efficient mobilization of resources, and a highly developed division of labor. However, details about the structure of government and the social system are difficult to tease out of the sources. Careful study of the fragmentary writings and artifacts has offered glimpses of the Shang elite, but information about commoners is scant, and knowledge of their lives and values will probably remain limited.

The key figures in the elite were the king and the royal family. As the oracle bones attest, the king was clearly the main diviner, a ritual and religious function that at some early stage translated into secular political power. As he expanded his authority in the capital at Anyang, he instructed specific clans to settle in new towns and provided their leaders with tangible symbols of power, helping to legitimize their rule in these sites. The kings and their consorts derived from a small group of clans, among whom the royal succession rotated. Because primogeniture was not the norm, officials who were part of the elite advised the king on the choice of a suitable successor who could assume the religious, political, and military responsibilities. The king’s ritual tasks evolved throughout the dynasty but always involved offerings to the ancestors and earlier kings, as well as divinations concerning war, hunts, and other matters of importance. Depending on the era, kings also made offerings to deities associated with nature or performed rituals to produce more bountiful harvests.

Elite status conferred privileges and responsibilities on both men and women. Royal consorts played an active role in the public sphere. They could conduct sacrifices and act in the name of the king, and at least one took part in a military campaign. In short, they played active social roles rather than spending their lives in the shadowy private spheres of household and harem. Other members of the elite included princes, diviners, ministers, officials, and landlords who were granted land or walled towns by the king. Members of the elite had the right to accompany the king on hunts, which were often used to train the military, and to assume the responsibility of supporting him on military expeditions. By participating in the hunts, they had access to the animals bagged – a valuable resource for their own domains. In theory, the land accorded them was still owned by the king, and they were obligated to offer tribute to him. In practice, however, distance and time influenced the king’s ability to control them and to demand and receive tribute. The farther away their domains from the capital, the less leverage the king could have over them. Similarly, at times when weak monarchs were on the throne, they fulfilled their obligations with neither alacrity nor regularity. Yet their power derived from the titles that the king conferred upon them as lords over walled towns within the Shang state.

The princes and lords commanded the armies, but the social status of the military is not discernible from the sources. Naturally the king was the commander in chief of the state’s army, and the princes and lords led the military within their own domains – the military forces that could be mobilized were apparently sizable. Descriptions of the battles, of the captives, and of the human sacrifices of prisoners of war in the tombs of the elite attest to the participation of substantial numbers of soldiers in particular campaigns. The military achieved a degree of specialization, with specific units of archers, foot soldiers, and charioteers who used bows and arrows, halberds, and chariots.

Knowledge of the nonelite is even sketchier. The divination inscriptions describe what appear to be collectives of peasants who worked under the strict supervision of the king and lords. They worked together to farm the fields, served as soldiers, offered tribute, and were compelled to perform corvée labor. Although most were servile, labeling them “slaves” is an overstatement. Unlike slaves, most could not be bought or sold. To be sure, slavery existed in the Shang; prisoners of war were often enslaved and forced to work in the fields or were sacrificed at tombs of kings or lords. Yet the vast majority of the nonelite were not slaves, although they undoubtedly were accorded little status, were economically exploited, and were dominated by the kings and lords. As suggested earlier, artisans had a higher position in the social hierarchy, lived more comfortably, and had access to more goods than ordinary commoners. Specific clans dominated particular trades such as woodcarving, bronze casting, and jade carving, and craft production was often a monopoly transmitted from one generation to another.

Although records on finances are absent, it appears that the king collected taxes from all his subjects. He received tribute of grain, principally millet, from the peasants, who also sent cattle (for his divinations), sheep, and horses to the capital. During his hunts (and possibly tours of inspection), he also requisitioned supplies from the peasants for his entourage. The quantity of taxes levied by the king is not recorded, but it must have been sufficient to pay for military campaigns and the elaborate tombs and other material possessions of the royal household. Simultaneously, the king received goods that the artisans had fashioned. The furnishings at the royal tombs, as well as those of the elite, attest to the considerable number of bronzes, jades, and pottery items commandeered from craftsmen. Merchants surely played a role in transmitting grain and craft articles from the various towns to the capital and vice versa, but they are scarcely mentioned on the oracle bones. Cowry shells were used as currency, and the modern Chinese word for “merchant” ( shangren ) uses the same Chinese characters as “man of Shang.” Yet the paucity of data precludes efforts to assay the role of trade and the status of merchants during this era.

Читать дальше