Despite these lacunae, archeological data and written inscriptions reveal considerable development in almost every area of endeavor. The Shang, the dates of which are still in dispute, though it certainly ended in 1028 BCE, witnessed remarkable changes from Neolithic cultures. Cities rather than towns were built. Rituals and ceremonies were more elaborate, and a recognizable system of writing was created. The populations of the cities were larger, necessitating a more complicated social system. Nearly every site and institution was on a larger scale than in the Neolithic.

The modern city of Anyang (in modern Henan province), in which the Shang capital of Yin was located, has turned out to be a treasure house of Shang civilization. The site stretches beyond the old city walls of Anyang to include small villages and tomb complexes. The village of Xiaotun, the principal site thus far excavated, consisted of rectangular houses with stamped-earth bases, large tombs adjacent to smaller burial pits, and ritual areas also with burial pits. The excavations indicate that Xiaotun was inhabited prior to the shifting of the capital. Even in this early period, the several hundred or so residences uncovered had drainage ditches, and graves of seemingly important individuals contained bronze ritual vessels, as well as the remains of human sacrifices.

With the establishment of the capital near Xiaotun, the buildings assumed larger proportions – evidence of a more sophisticated society. The inhabitants erected several large above-ground structures, some with thirty layers of stamped earth, which have been identified as palaces and temples. The sizable quantity of below-ground pit dwellings, which contained animal bones, pottery, and tools, attest to the large number of ordinary residents who farmed the fields or acted as service personnel for the palace inhabitants. Enormous underground storage pits, which preserved the goods of the royal family and the elite, and numerous bronze, jade, and stone workshops were built near the palaces. Also adjacent were colossal tombs, with human and dog sacrifices; sixteen people (men, women, and children) were sacrificed in one such tomb. Precious objects overflowed within the pit, the coffin, and other parts of the grave. Hundreds of jades, bronzes, and pottery vessels, among other goods, were scattered throughout the tombs. Other objects placed in the tombs included weapons, musical instruments, and cowry shells (which were used as money).

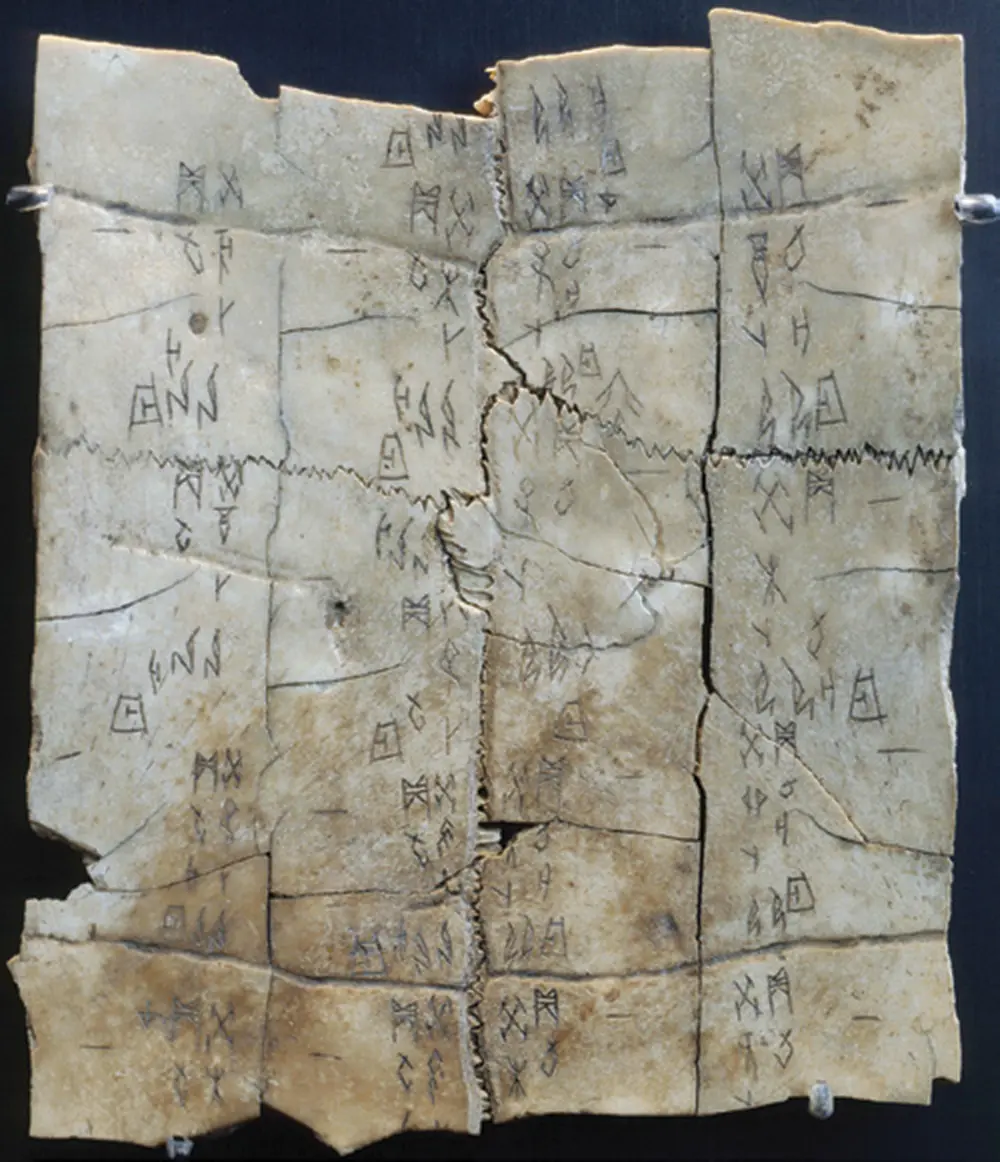

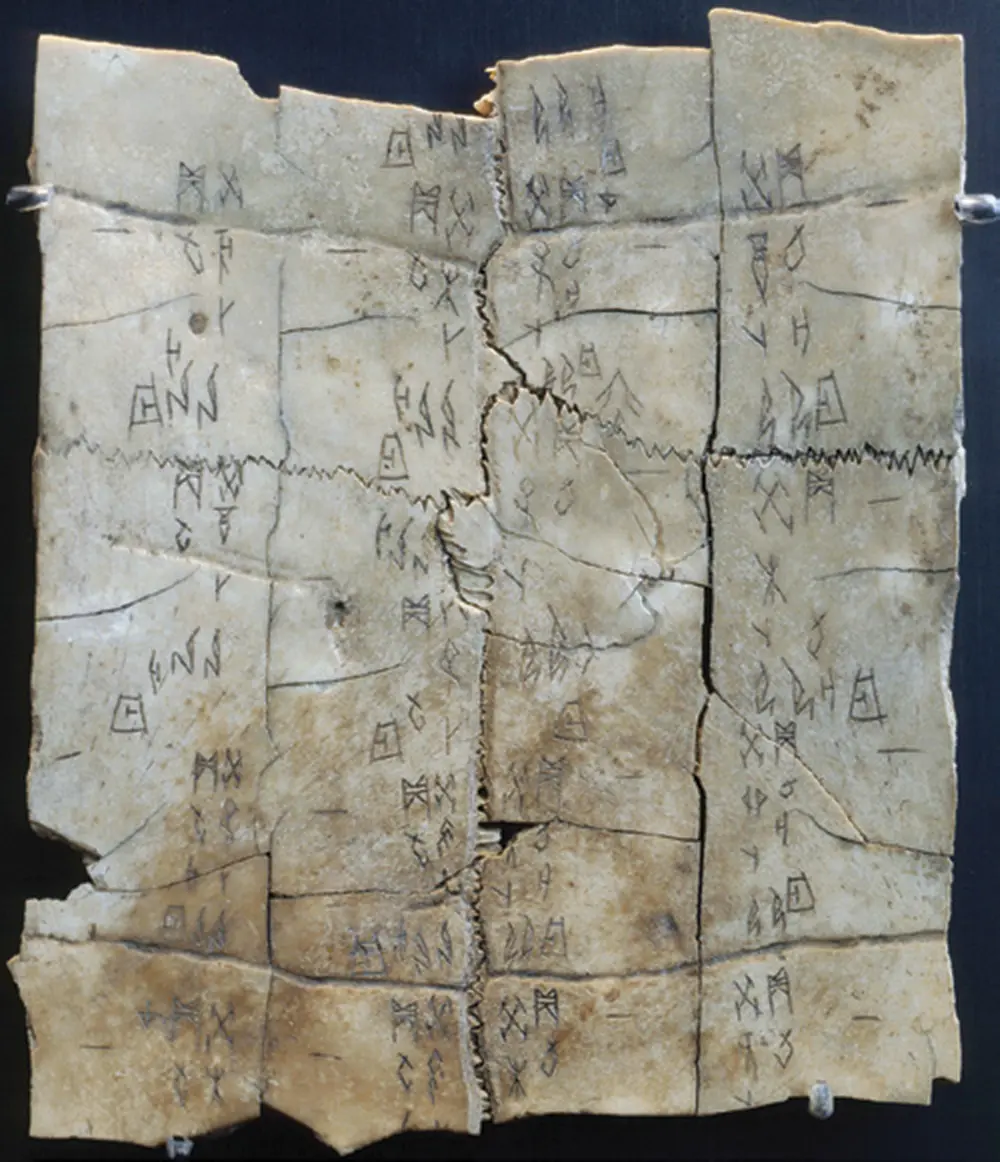

Knowledge of the Shang has emerged not only from the era’s physical remains but also from oracle-bone inscriptions, of which about 100,000 pieces have survived. The Shang advanced beyond the Neolithic forms of scapulimancy in using turtle shells (generally female) along with cattle bones in divination and incising responses on the scapula, thus producing the first conscious Chinese writing. Workmen chiseled or bored holes in the bone or shell, and diviners applied heat and produced cracks, which were then interpreted. A craftsman, perhaps the same workman, recorded the circumstances surrounding the actual divination – the date and the name of the diviner (who, as the Shang progressed, was almost always the king) as well as its actual content. Divinations concerned potential military ventures and hunting expeditions, the harvests, sacrifices to the ancestors, and the weather and other natural phenomena.

Figure 1.3Tortoise shell with divinatory text of the reign of Geng Ding, Shang dynasty, fourteenth/thirteenth century BCE. The Art Archive/Musée Guimet Paris/Gianni Dagli Orti.

The diviners sought responses from the ancestors and from Di (who was particularly identified with the Shang royal family), a deity who, along with the river, mountain, and wind gods, controlled the natural world as well as warfare, illness, and other human crises. The king’s interpretation of the cracks foretold the future. On occasion, the bones recorded the actual outcome, which most often confirmed the prognostication. The whole operation – the chiseling of holes, the proper creation of systematic cracks, and the recording of the divination – required enormous effort, time, and expertise, indicating divination’s value to Shang society.

The oracle bones afford glimpses of Shang society. Nearly every aspect of Shang culture, from agriculture to sickness to the interpretation of dreams, was addressed in these records of divination. Since the king himself, reflecting a theocratic system, was the principal diviner, the bones often convey the objectives and aspirations of the elite, as well as their spiritual views. However, Shang religions consisted of more than oracle bones. The bones themselves allude only to rituals, dances, music, and ceremonies, without providing additional details. Thus, they convey only a partial – though invaluable – view of Shang religion and society. Though the bones that have survived constitute less than ten percent of the total actually produced for divination, most specialists believe that they are representative in theme and subject matter of the rest. Some historians believe that the divination inscriptions provide a general picture of the elite’s worldviews; they also recognize that knowledge of Shang China will not, unless new remarkable sources are uncovered, achieve the same level of detail about rulers, the military, and the economy as exists regarding later dynasties.

RITUAL OBJECTS AS HISTORICAL SOURCES

Other sources that provide information about the Shang include signs and actual writings on bones, pottery, and jade, but no doubt the most important are ritual bronze vessels. The bronzes reflect sophistication and advances in arts and crafts but also yield information on religion, social relations, and government. Some of these data derive from fragmentary and sometimes cryptic inscriptions on the bronzes. Unlike the bronze inscriptions of the next dynasty, the Zhou, the Shang artifacts are brief, none amounting to more than fifty Chinese characters. Nonetheless, they occasionally narrate the circumstances under which the bronzes were cast, for several were produced to commemorate military expeditions, gifts, or special rituals. Many were designed for ritual purposes and served as drinking vessels, food containers, or cooking implements on ceremonial occasions. Bronze craftsmen also fashioned musical instruments, chariots, weapons, and farm tools.

Figure 1.4Bronze vessel bearing the taotie design, Shang dynasty. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library.

In addition, the decorations on the bronzes may yield insights about the Shang ethos and religion. Descriptions of fantastic animals, which sometimes combined features of different animals, were characteristic of the motifs found on the bronzes. The so-called taotie mask is the most distinctive of these mythical figures. Readily recognized by its prominent and large eyes, which gaze directly at the observer, the taotie has puzzled scholars who have tried to understand its possible ritual or religious importance. Speculation on its meaning ranges from its use to protect humans to its identification as a grotesque, malevolent monster. What appear to be its jaws, as well as its horns and snout, give it a ferocious appearance, but its symbolic significance remains elusive. There are also variations in the depictions of the taotie in the Shang bronzes, and the eyes often are the only means to identify the creature. A number of other animals, including dragons, are represented, although once again their precise meaning is unclear.

Читать дальше