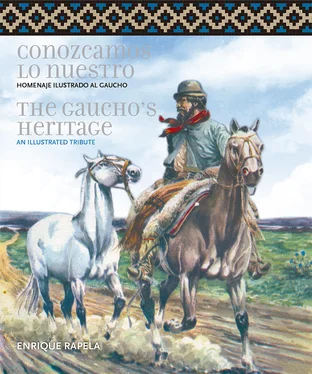

La editorial Cielosur da origen a revistas de varios tamaños y períodos: mensual, álbum o fascículo. En las tiras se destinaba un segmento al origen de las palabras como pulpería, sangría, ranqueles. Esta pasión de Rapela por ampliar los conocimientos del lector consigue que aparezca una sección especial llamada Conozcamos lo nuestro , descripta como “una singular enciclopedia de terminología campestre”, que en 1977 y en exitosas ediciones posteriores, ya se publicaban en tres tomos. En los diálogos de ambas historietas se intenta reflejar el habla gauchesca y se reproducen muchas de sus expresiones. Se puede decir que ambos héroes –El Huinca y Fabián Leyes aparecidos en Patoruzito y el diario La Prensa respectivamente, durante la década de 1970– son gemelos arquetípicos de justicieros que, junto a sus laderos, ayudan al prójimo. El acompañante del primero es Zenón y el del segundo, Amancio. “Para eyos [sic], ésa es su vida, pampa y cielo. Guadal y pajonales. Libres como el viento, alegres como los pájaros cuando nace el día”, se afirma en una de las tiras. Aunque también eran contratados alternativamente como guías para las partidas exploratorias que circulaban en torno a los fortines por su conocimiento de la llanura y el entorno.

A ese valor emprendedor y didáctico se une el estético, ya que si enfocamos en el arte de Rapela, hay que destacar especialmente las imágenes donde registra el paisaje retratando un cielo sereno con sutiles rayas verticales; o cuando describe unas siluetas negras con ligeros toques blancos que señalan la luz lunar en contraste con las figuras. La vestimenta y el tipo de tela se nota en sus arrugas que están representadas con soltura, como también se describen los ranchos, los senderos, los árboles y las diligencias. Se trata de un dibujo sobrio, aplomado, clásico, pero con grises que enriquecen no solo la composición, sino que funcionan como ornato. Son dibujos frescos, de trazos vigorosos y oficio diestro en el uso del pincel y la pluma. Pero destaca especialmente por los dibujos de caballos, con excelentes planos que detallan la anatomía de sus cabezas o el galopar de sus patas, así como la montura y el detalle del apero. “Supo reflejar gráficamente las llanuras inconmensurables que parecen proyectarse al infinito”, sostiene el escritor Germán Cáceres, él mismo un ideólogo de la cultura gauchesca. Falleció en Buenos Aires a la edad de 67 años, pero su impronta trasciende claramente su corta vida.

PILAR ALTILIO

Licenciada en Arte por la UNLP, Posgrado Internacional Gestión y Política en Cultura y Comunicación FLACSO Argentina. Docente de nivelación de posgrado en Prácticas artísticas contemporáneas UNCuyo. Gestora y curadora independiente desde 1999. Como investigadora independiente y crítica de arte publica regularmente en Revista Ñ de Cultura, ArtNexus revista colombiana, arte-online.net y El Gran Otro.

Fuentes: Judith Gociol y Diego Rosemberg, La historieta argentina. Una historia . Ed. De la Flor, Carlos G. Landa y Julio César Spota Trazos fronterizos en http://www.gazeta-antropologia.es/?p=1477

In the circulating biographies of Enrique José Rapela (1911- 1978), some precise strokes stand out. Even though he completed high school, he was a self-taught person regarding drawing and watercolor. Descendant from an immigrant family but seventh generation of Argentine people, he was a direct expert on gauchos’ topics because he administered La Carolina, his mother’s estancia, in Roque Pérez, close to Mercedes, in the province of Buenos Aires, where he was born. He was a passionate entrepreneur, scriptwriter, draftsman, editor, writer and historian, living in a golden age where great paradigms reunite: the historical revisionism of the 1960’s and 1970’s; the boom of graphic media —both magazines and newspapers were read by thousands of people all the time and the whole week—; and, finally, the profuse spreading of the national folklore with performers like Los Chalchaleros, Los Cantores de Quilla Huasi, Horacio Guarany, Eduardo Falú, and the boom of festivals and peñas [meetings where folk songs are played].

The native was consumed and spread in the city, but the morning graphic media were the place where the Creole cartoon was established as a genuine genre. In Cirilo el Audaz, published in the newspaper La Razón in 1939, Rapela narrates the adventures of Cirilo Cuevas, a gaucho who runs away from the law and seeks protection in the lines of Rosas’ army. The outline of that cartoon is repeated later with other characters and it becomes an archetype that perceives authority as aggressive and corrupt, and for that reason prefers to stay outside the law. There are historical-political references, like the Campaign of the Desert, the War of Paraguay; and personalities of our history, like Nicolás Avellaneda, Adolfo Alsina or Juan Manuel de Rosas are mentioned. The text was not in the typical speech balloons of the cartoons; it was located under the drawings. Regarding the speech, there is a nationalistic view that defends the countryside, through the archetype of a hero who can do everything with very few elements. In this way, in the whole cartoon, the gaucho, to a large extent alone with his strength, his ingenuity and some kind of luck in his favor, became a winner.

This didactic involvement with the diffusion of this environment could be placed after 1872, when, as the Argentine historian Bonifacio del Carril held, the gauchos were a true social class. Rapela himself said in a conference: “In this way we will understand that this wonderful country was not inhabited by useless barbarians, lazy people with bad habits, as a huge systematic and perfectly organized campaign, supported by people who only conceived as civilized what comes from overseas, rejecting the Latin Hispanic origin, repeated”. He was clearly opposed to a matrix that fostered the appearance of a new kind of citizenship that justified “domesticating the wild”. For that reason, the time chosen is the same of the conflict between Domingo Sarmiento and Juan Manuel de Rosas, an epic that turn into the book Civilización y barbarie. Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga y aspectos físicos, costumbres y hábitos de la República Argentina (1845), where the gaucho was pointed out as the main responsible for the cultural backwardness that stopped the development of the country. It is an essential node of our history, but also the result of the imaginary of the time, where extending the limits was imperative to get access to the organization of the Nation State.

Due to this revisionist trend, the archetype of the gaucho outstands thanks to the features of an already obsolete orality in the countryside, such as “apestao” or black “virgüela”. Also the garments were recreated after having access to documents from historical museums, to the point that even the drawn weapons were trustworthy descriptions used in that time. That vocation for the graphic representation of the material culture —both in Rapela and in some of his peers— was increased by the degree of closeness to the countryside environment of the plains, but it was based on historical research and literature by authors who described the period, which configures a didactic value that provided certified information to generations.

Carlos Gilberto Landa and Julio César Spota, from anthropology and historical archeology, went deep, in an article, about the relevance of Argentine cartoon, because some thematic relations, true critical revisions regarding the process that conformed the national past were developed there, emphasizing that “cartoon rose, through aesthetic means of massive diffusion, as an alternative approximation to that past”. The authors understand that the modern concept of frontier was anticipated in the gauchos’ cartoons by “elements of reflection related to processes of intercultural contact, dialog and conflict that were incorporated only in the 1980’s as a paradigm of common reference within the circles of anthropological-historical discussion”. The setting of works like Cabo Savino , by Carlos Casalla; Lanza Seca , by Guillermo Roux; El Huinca , by Enrique Rapela; Martín Toro , by Jorge Morhain and Bernoy in the drawings; Lindor Covas , el Cimarrón, created by Walter Ciocca; Capitán Camacho , with a script by Julio Álvarez Cao and drawings by Carlos Casalla –just to mention some titles of the extensive artistic production— showed, in their entire complexity, the different social links, the ways of cultural exchanges, and the case of the mutual economic dependencies existing among the white, the indigenous and the mestizo groups.

Читать дальше