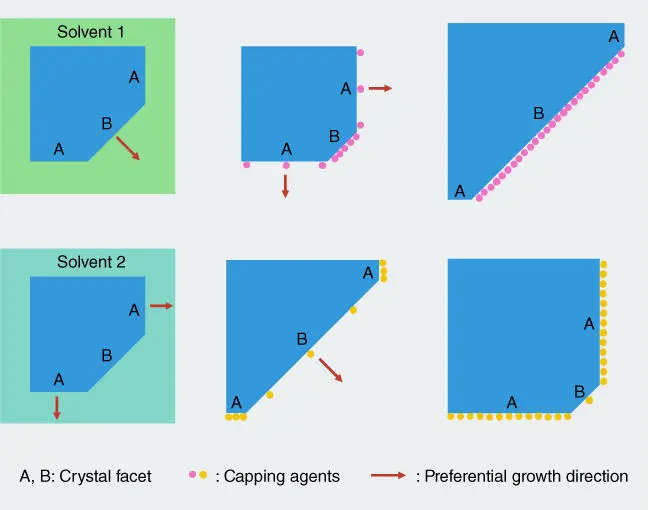

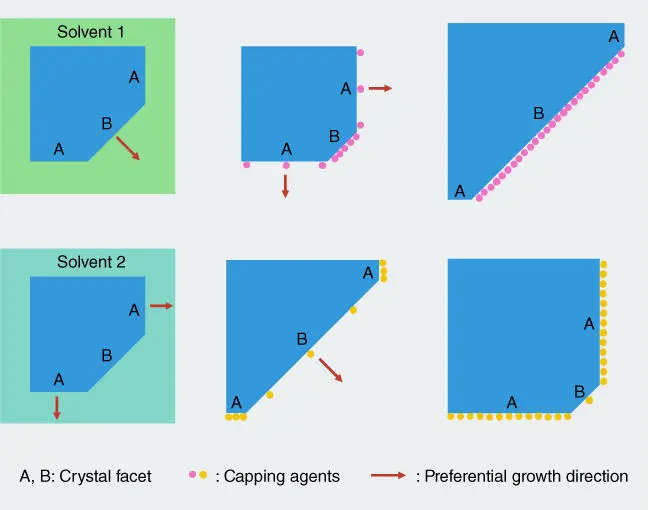

Figure 2.2 Schematic of the effect of solvent and capping agents on the morphology control of crystal facets.

Source: Adapted from Liu et al. 2011 [23].

Selectivity and adsorption capability of the capping agents, regardless of organic or inorganic capping agents, are basically controlled by the density and arrangement of undercoordinated atoms on different surfaces. The capping agents stabilize these high‐energy surfaces by covering the undercoordinated atoms. This also means that the reactive sites on the surfaces are also likely to be covered. For instance, fluorine is the most frequently used capping agent for faceted TiO 2crystals. Fluorine always exists in the surface of as‐prepared faceted TiO 2crystals. Pan et al. demonstrated that the fluorine‐terminated anatase TiO 2crystals with different percentages of {001}/{101}/{010} facets have similar low photocatalytic performance. After the removal of fluorine by calcination, all TiO 2crystals exhibited much higher and diverse performance depending on the ratio of different facets. Although most studies suggest that the removal of the surface fluorine improves the performance in photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from water splitting with sacrificial agents, in some cases, the capping agents may also tune the activity and selectivity of the catalysts by involving in the catalytic process.

Another strategy to tailor the crystal morphology is via the top‐down route, where a starting particle sample is selectively etched to remove the undesirable facets. This method is more often used in the synthesis of semiconductors. The protective capping agents can be used to shield the desirable facets, leaving the uncapped and unwanted facets to be dissolved in the etching process. For instance, truncated octahedral Cu 2O crystals can be synthesized via the hydrothermal method by using PVP as a capping agent. PVP is preferentially adsorbed on the Cu 2O{111} facet. And then, in the following oxidative etching process, PVP can protect the Cu 2O{111} facet. As a result, the truncated octahedral Cu 2O crystals turned into a hollow structure with six {100} facets absent [31]. In some cases, even without any protective agents, selective etching can be used to prepare hollow structures, due to anisotropic corrosion of different facets. For example, a rectangular rutile TiO 2nanorod can be selectively etched along the [001] direction in hydrochloric acid, turning into a hollow rutile TiO 2tube. This is because the rutile TiO 2{001} facets have a higher dissolution rate than the {110} facets [32].

2.3 Anisotropic Properties of Crystal Facets

The properties of crystal surface differ from the ones inside crystal bulk, due to the termination of the periodic arrangement of the atoms. The anisotropy of the crystal lattice determines the anisotropy of the atomic arrangement of the facets exposed, leading to anisotropic properties of the crystal surface.

2.3.1 Anisotropic Adsorption

Heterogeneous reaction takes place on a catalyst surface (most commonly as solid) where phase differs from that of the reactants [33]. In a typical case, the process consists of three steps, adsorption, reaction, and desorption occurring at the catalyst surface. The effective adsorption, which is an essential step during heterogeneous reaction, is largely related to the exposed atomic structures of the catalyst surface. Because the surface atomic arrangement and coordination vary in different crystal facets, adsorption energy and states of the reactant molecules are different on various exposed facets. This variation of adsorbing states has a profound impact on the subsequent catalytic steps.

Various surface science studies have been performed to investigate the interactions between the different surface facets of metals or semiconductors, and the reactant molecules. Platinum, being one of the most versatile metal catalysts, has an fcc crystal structure and is one of the most studied surfaces. On the flat surface, such as Pt{100} and Pt{111}, each platinum atom is surrounded by four and six adjacent neighbors, respectively. These two low‐index facets have highest atomic density. High‐index facets, such as Pt{530} and Pt{730}, contain many terrace structure and steps with low‐coordinated atoms [34]. The atomic arrangement of Pt{730} facet is periodically overlapped with one Pt{310} subfacet and two Pt{210} subfacets, leading to a multiple‐height terrace structure. Furthermore, the faceted metal catalysts have more atoms located at the edges and corners, where they have much lower atomic density and coordination, which can have a profound impact on surface adsorption.

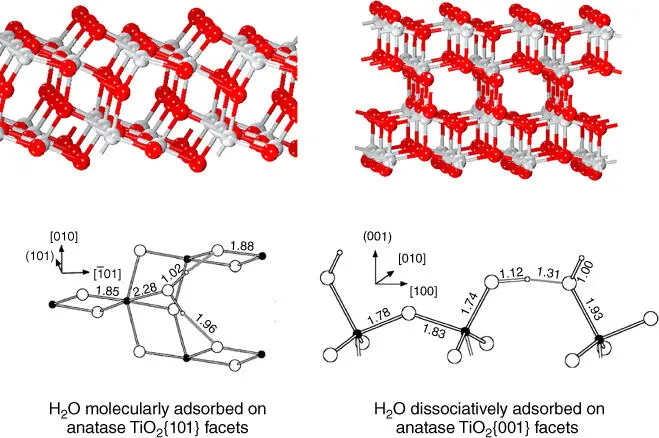

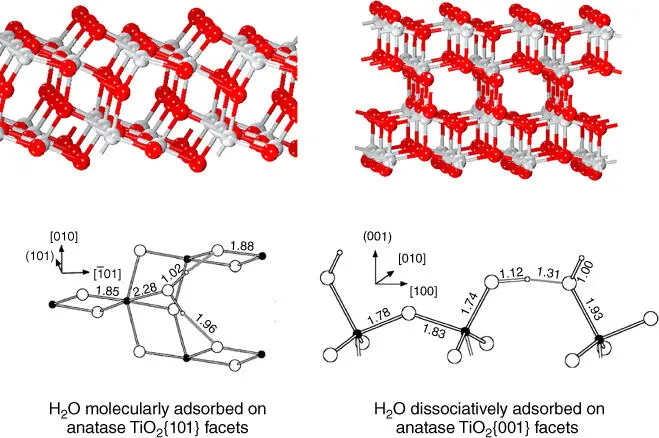

Titanium dioxide (TiO 2) has been the most intensively investigated binary transition metal oxide as a photocatalyst, where many theoretical calculations have been conducted to investigate the interactions between water molecules and the TiO 2surface [35]. Because the water molecule is one of the most important adsorbates present in many photocatalytic reactions, such as water splitting, photodegradation of organic pollutants, and CO 2reduction, many experimental and theoretical studies have focused on this aspect [36–40]. Anatase {101}, {001}, and {100} surfaces are three typical low‐index surfaces of anatase TiO 2. Anatase {101} contains 50 % sixfold coordinated (Ti 6c) Ti atoms (saturated) and 50 % fivefold coordinated (Ti 5c) Ti atoms (unsaturated), whereas anatase {001} and {100} surface contains 100% Ti 5catoms. Most theoretical and experimental results suggest molecular adsorption of water on the defect‐free {101} surface [41] but dissociative adsorption of water molecules on the {001} surface at low coverages (shown in Figure 2.3) [36]. The dissociative adsorption of water is also favorable on the anatase {100} surface [12].

Figure 2.3 Side view of anatase TiO 2{101} and {001} facets. Top view for adsorbed water molecules on anatase {101} surface and side view of adsorbed water molecules on anatase {001} surface.

Source: Vittadini et al. 1998 [36]. Reproduced with permission of American Physical Society.

2.3.2 Surface Electronic Structure

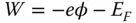

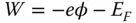

Anisotropic electrical properties of surfaces are logically attributed to the anisotropy of the crystal lattice, which determines the different atomic arrangements and configurations depending on exposed facets. Work function is the minimum energy for valence electrons in the solid to overcome in order to exit into the vacuum [42], which can be defined as

where for elemental metals, E Fis the potential energy of the electrons at the top of the valence band (VB) called the Fermi level, − e is the charge of an electron, and ϕ is the electrostatic potential in vacuum. For elemental metals, work function highly depends on the crystallographic orientation of the surface, as atomic density and electron charge density vary across different facets. The difference of work function between two surfaces of the same metal in different orientation can reach up to 1 eV [43]. For example, work functions of tungsten W{001} facet, W{112} facet, and W{111} facet are 4.56 eV, 4.69 eV, and 4.39 eV, respectively [44]. Work function of polycrystalline Ag is 4.26 eV, but work functions of Ag{100} facet, Ag{110} facet, and Ag{111} facet are 4.64 eV, 4.52 eV, and 4.74 eV, respectively [45]. Furthermore, surface roughness and particle size also have a profound impact on work function.

Читать дальше