Fig. 399. Eskimo awaiting return of seal to blowhole. (From a photograph.)

Ross (II, p. 268) and Rae (I, p. 123) state that the sealing at the hole is more difficult in daylight than in the dark. I suppose, however, that when the snow is deep there is no difference; at least the Eskimo of Davis Strait never complain about being annoyed by the daylight.

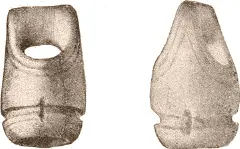

Fig. 400. Tuputang or ivory plugs for closing wounds. e (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin. IV A 6706.) b , c , d (National Museum, Washington. b , 10192; c , 10390; d , 9836.) 1/1

Sometimes a small instrument is used in the hunt to indicate the approach of the seal. It is called qipekutang and consists of a very thin rod with a knob or a knot at one end (Parry II, p. 550, Fig. 20). It is stuck through the snow, the end passing into the water, the knob resting on the snow. As soon as the seal rises to blow, it strikes the rod, which, by its movements, warns the Eskimo. Generally it is made of whalebone. Sometimes a string is attached to the knob and fastened by a pin to the snow, as its movements are more easily detected than those of the knob. The natives are somewhat averse to using this implement, as it frequently scares the seals.

Fig. 401. Wooden case for plugs. (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.) 1/1

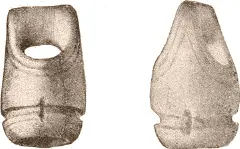

Fig. 402. Another form of plug. (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.) ⅔

Fig. 403. Qanging for fastening thong to jaw of seal. a (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin. IV A 6825.) b , c (National Museum, Washington. b , 34126; c , 34129.) 1/1

Fig. 405. Qanging in form of a button. (National Museum, Washington. 34130.) 1/1

After the carcass of the animal has been drawn out of the water, the wounds are closed with ivory plugs (tuputang) (Fig. 400), which are carried in a wooden or leathern case (Fig. 401) and are either triangular or square. The plug is pushed under the skin, which is closely tied to its head. Another form of plug which, however, is rarely used, is represented in Fig. 402. The skin is drawn over the plug and tied over one of the threads of the screw cut into the wood. After the dead animal’s wounds are closed, a hole is cut through the flesh beneath the lower jaw and a thong is passed through this hole and the mouth. A small implement called qanging is used for fastening it to the seal. It usually forms a toggle and prevents the line from slipping through the hole. The patterns represented in Fig. 403 are very effective. The hole drilled through the center of the instrument is wider at the lower end than elsewhere, thus furnishing a rest for a knot at the end of the thong. The points are pressed into the flesh of the seal, and thus a firm hold is secured for the whole implement. The Eskimo display some art in the manufacture of this implement, and frequently give it the shape of seals and the like (Fig. 404). Fig. 405 represents a small button, which is much less effective than the other patterns. A very few specimens consist merely of rude pieces of ivory with holes drilled through them. Fig. 406 shows one of these attachments serving for both toggle and handle.

Fig. 404. Qanging in form of a seal. (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin. IV A 6825.) 1/1

Fig. 406. Qanging serving for both toggle and handle. (National Museum, Washington. 10400.) ⅔

In order to prevent the line from getting out of order, a whirl (qidjarung) is sometimes used. Fig. 407 represents one brought from Cumberland Sound by Kumlien, and is described by him (p. 38). There was a ball in the hollow body of this instrument, which could not be pulled through any of the openings. One line was fastened to this ball, passing through the central hole, and another one to the top of the whirl. A simpler pattern is represented in Fig. 408.

Fig. 407. Qidjarung or whirl for harpoon line. (National Museum, Washington. 34121.) 1/1

Fig. 408. Simpler form of whirl. (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.) 1/1

On its capture, the seal is dragged to the sledge and after being covered with the bearskin is firmly secured by the lashing. It freezes quickly and the hunter sits down on top of it. If the seal happens to blow soon after the arrival of the hunter, a second one may be procured, but generally the day is far spent when the first seal is killed.

Wherever water holes are found they are frequently visited during the winter by the Eskimo, especially by those who have firearms. They lie in wait at the lower side of the hole, i.e., the side to which the tide sets, and when the seal blows they shoot him, securing him with the harpoon after he has drifted to the edge of the ice. These holes can only be visited at spring tides, as in the intervals a treacherous floe partly covers the opening and is not destroyed until the next spring tide.

In March, when the seal brings forth its young, the same way of hunting is continued, besides which young seals are eagerly pursued. The pregnant females make an excavation from five to ten feet in length under the snow, the diving hole being at one end. They prefer snowbanks and rough ice or the cracks and cavities of grounded ice for this purpose, and pup in these holes. The Eskimo set out on light sledges dragged by a few dogs, which quickly take up the scent of the seals. The dogs hurry at the utmost speed to the place of the hole, where they stop at once. The hunter jumps from the sledge and breaks down the roof of the excavation as quickly as possible, cutting off the retreat of the seal through its hole if he can. Generally the mother escapes, but the awkward pup is taken by surprise, or, if very young, cannot get into the water. The Eskimo draws it out by means of a hook (niksiang) and kills it by firmly stepping on the poor beast’s breast. An old pattern of the hook used is represented according to Kumlien’s drawing in Fig. 409; another, made from a bear’s claw, in Fig. 410; the modern pattern, in Fig. 411.

Читать дальше