The general principles of their construction are well known. The kayak of the Nugumiut, Oqomiut, and Akudnirmiut is bulky as compared with that of Greenland and Hudson Bay. It is from twenty-five to twenty-seven feet long and weighs from eighty to one hundred pounds, while the Iglulik boats, according to Lyon (p. 322), range from fifty to sixty pounds in weight. It may be that the Repulse Bay boats are even lighter still. According to Hall they are not heavier than twenty-five pounds (II, p. 216).

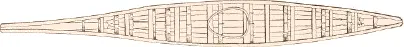

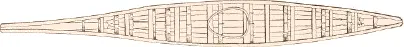

Fig. 413. Frame of a kayak or hunting boat. (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.)

The frame of the kayak (Fig. 413) consists, first, of two flat pieces of wood which form the gunwale (apumang). From ten to twenty beams (ajang) keep this frame on a stretch above. The greatest width between them is a little behind the cock pit (p. 487). A strong piece of wood runs from the cross piece before the hole (masing) to the stem, and another from the cross piece abaft the hole (itirbing) to the stern (tuniqdjung). The proportion of the bow end to the stern end, measured from the center of the hole, is 4 to 3. The former has a projection measuring one-fourth of its whole length. Setting aside the projection, the hole lies in the very center of the body of the kayak. A large number of ribs (tikping), from thirty to sixty, are fastened to the gunwales and kept steady by a keel (kujang), which runs from stem to stern, and by two lateral strips of wood (siadnit), which are fastened between gunwale and keel. The stem projection (usujang), which rises gradually, begins at a strong beam (niutang) and its rib (qaning). The extreme end of the stern (aqojang) is bent upward. The bottom of the boat is partly formed by the keel, partly by the side supports. The stern projection has a keel, but in the body of the boat the side supports are bent down to the depth of the keel, thus forming a flat bottom. Rising again gradually they terminate close to the stern. Between the masing and the itirbing is the hole (pa) of the kayak, the rim of which is formed by a flat piece of wood or whalebone bent into a hoop. It is flattened abaft and sharply bent at the fore part. The masing sometimes rests upon a stud.

Fig. 414. Kayak with covering of skin. (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.)

The whole frame is covered with skins (aming) tightly sewed together and almost waterproof (Fig. 414). Usually the cover consists of three or four skins of Pagomys fœtidus . When put upon the frame it is thoroughly wetted and stretched as much as possible so as to fit tightly. It is tied by thongs to the rim of the hole. A small piece of ivory is attached to each side of the niutang and serves to fasten a thong which holds the kayak implements. Two more thongs are sewed to the skin just before the hole, another one behind it, and two smaller ones near the stern.

The differences between this boat and that of the Iglulirmiut may be seen from Lyon’s description (page 320). Their kayak has a long peak at the stern, which turns somewhat upward. The rim round the hole is higher in front than at the back, whereas that of the former has the rim of an equal height all around. At Savage Islands Lyon saw the rims very neatly edged with ivory. The bow and the stern of the Iglulik kayaks were equally sharp and they had from sixty to seventy ribs. While the kayaks of the Oqomiut have only in exceptional cases two lateral supports between keel and gunwale, Lyon found in the boats of these natives seven siadnit, but no keel at all. These boats are well represented in Parry’s engravings (II, pp. 271 and 508). Instead of the thongs, ivory or wooden holders are fastened abaft to prevent the weapons from slipping down.

If the drawing in Lyon’s book (p. 14) be correct, the kayak of the Qaumauangmiut (Savage Islands) has a very long prow ending in a sharp peak, the proportion to the stern being 2 to 1. Its stern is much shorter and steeper than that of the northern boats and carries the same holders as that of the Iglulirmiut.

Fig. 415. Model of a Repulse Bay kayak. (National Museum, Washington. 68126.)

Fig. 416. Sirmijaung or scraper for kayak. (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.) ½

Fig. 417. Large kayak harpoon for seal and walrus. Actual length, 6½ feet. (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.)

The model of a Repulse Bay kayak is represented in Fig. 415. The rim of the hole is in the same position as in the Iglulik kayak, the fore part resting on a rib bent like a hoop, whereas in the others it rests on a beam. The stern resembles closely that of the Cumberland Sound boats, while the head is less peaked, the keel having a sharper bend at the beginning of the projection, which does not turn upward. Early in the spring and in the autumn, when ice is still forming, a scraper (sirmijaung) (Fig. 416) is always carried in the kayak for removing the sleet which forms on the skin. When the boat has been pulled on shore, it is turned upside down and the whole bottom is cleaned with this implement. A double bladed paddle (pauting) is used with the boat. It has a narrow handle (akudnang), which fits the hand of the boatman and widens to about four inches at the thin blades (maling), which are edged with ivory. Between each blade and the handle there is a ring (qudluqsiuta).

The kayak gear consists of the large harpoon and its line (to which the sealskin float is attached), the receptacle for this line, the bird spear (with its throwing board), and two lances.

Fig. 418. Tikagung or support for the hand. a , b , c (National Museum, Washington. a , 30000; b , 30005; c , 30004.) d (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.)

The large harpoon (Fig. 417) is used for hunting seals and walrus from the kayak. The shaft (qijuqtenga) consists of a stout pole from four and a half to five feet in length, to which an ivory knob is fastened at the lower end. At its center of gravity a small piece of ivory (tikagung) is attached, which serves to support the hand in throwing the weapon. A remarkable pattern of this tikagung, which nicely fits the hand of the hunter, is represented in the first of the series of Fig. 418, and another one, which differs only in size from that of the unang, in the second. At right angles to the tikagung a small ivory knob is inserted in the shaft and serves to hold the harpoon line. At this part the shaft is greatly flattened and the cross section becomes oblong or rhombic. At the top it is tenoned, to be inserted into the mortice of the ivory head (qatirn). The latter fits so closely on the tenon that it sticks without being either riveted or tied together. The qatirn is represented in Fig. 419. Into the cavity at its top a walrus tusk is inserted and forms with it a ball and socket joint (igimang).

Читать дальше