Figure 1.15 The constriction of a blood vessel by the periodontal fibers. The flow of blood in the vessels is occluded by the entwining periodontal fibers. Below the stenosis, the pressure drop gives rise to the formation of minute gas bubbles, which can diffuse through the vessel walls. Above the stenosis, fluid diffuses through the walls of the cirsoid aneurysms formed by the build‐up of pressure.

(Source: Bien, 1966. Reproduced with permission of SAGE Publications.)

Pointing out a conceptual flaw in the pressure tension hypothesis proposed by Schwarz (1932), Baumrind (1969) concluded from an experiment on rodents that the PDL is a continuous hydrodynamic system, and any force applied to it will be transmitted equally to all regions, in accordance with Pascal’s law. He stated that OTM cannot be considered as a PDL phenomenon alone, but that bending of the alveolar bone, PDL, and tooth is also essential. This report renewed interest in the role of bone bending in OTM, as reflected by Picton (1965) and Grimm (1972). The measurement of stress‐generated electrical signals from dog mandibles after mechanical force application by Gillooly et al . (1968), and measurements of electrical potentials, revealed that increasing bone concavity is associated with electronegativity and bone formation, whereas increasing convexity is associated with electropositivity and bone resorption (Bassett and Becker, 1962). These findings led Zengo et al . (1973) to suggest that electrical potentials are responsible for bone formation as well as resorption after orthodontic force application. This hypothesis gained initial wide attention but its importance diminished subsequently, along with the expansion of new knowledge about cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions, and the role of a variety of molecules, such as cytokines and growth factors in the cellular response to physical stimuli, like mechanical forces, heat, light, and electrical currents.

Histochemical evaluation of the tissue response to applied mechanical loads

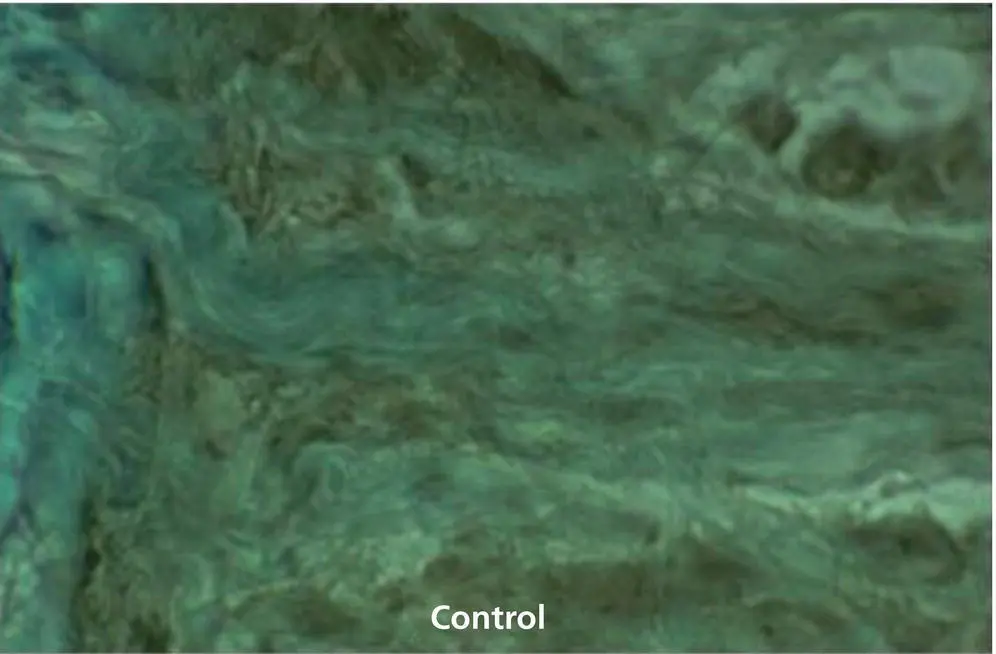

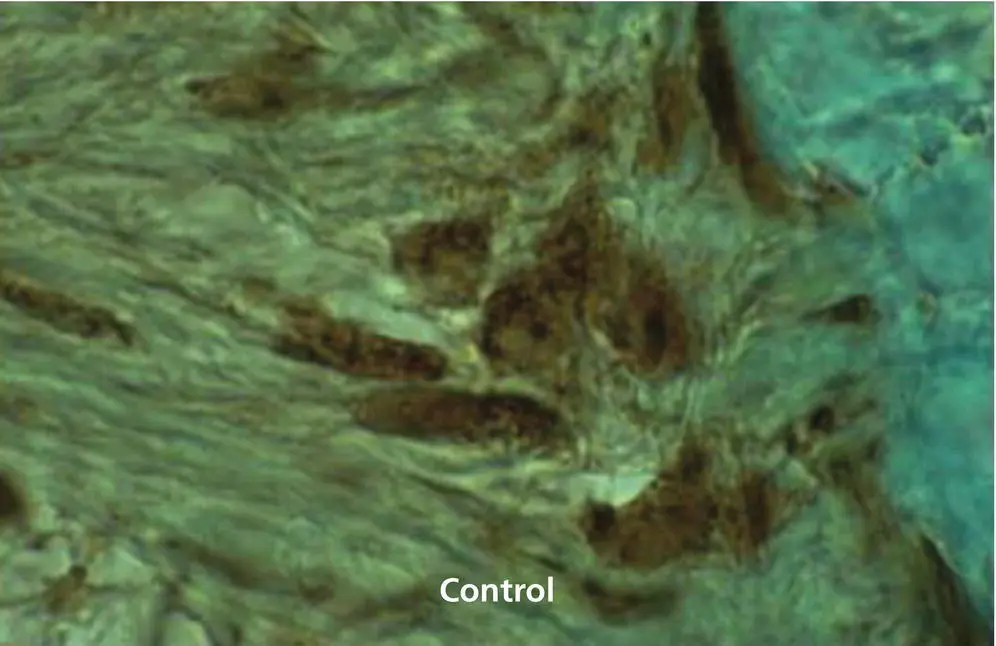

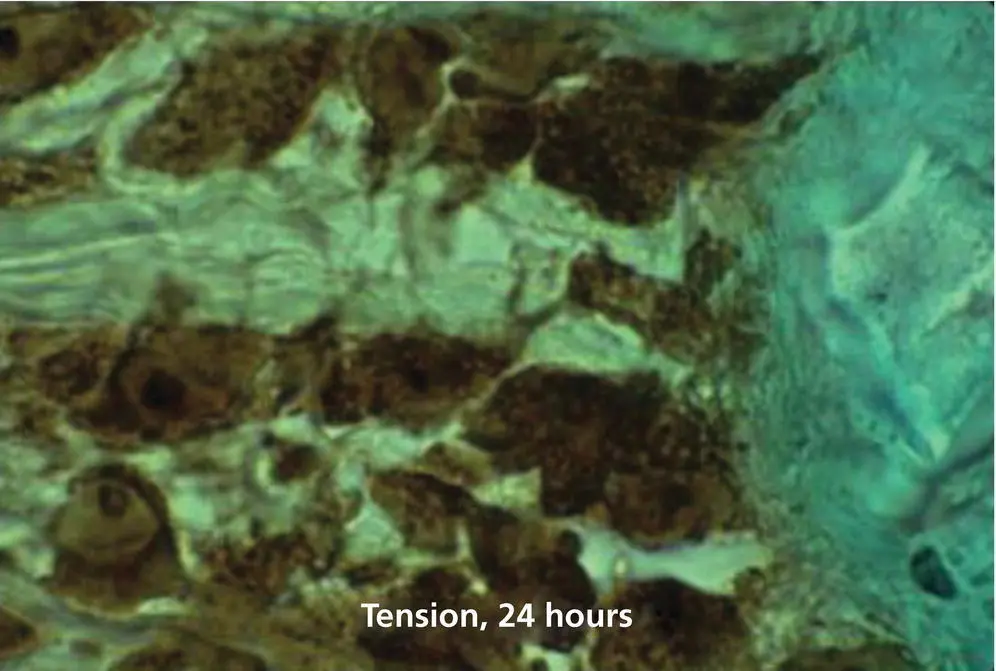

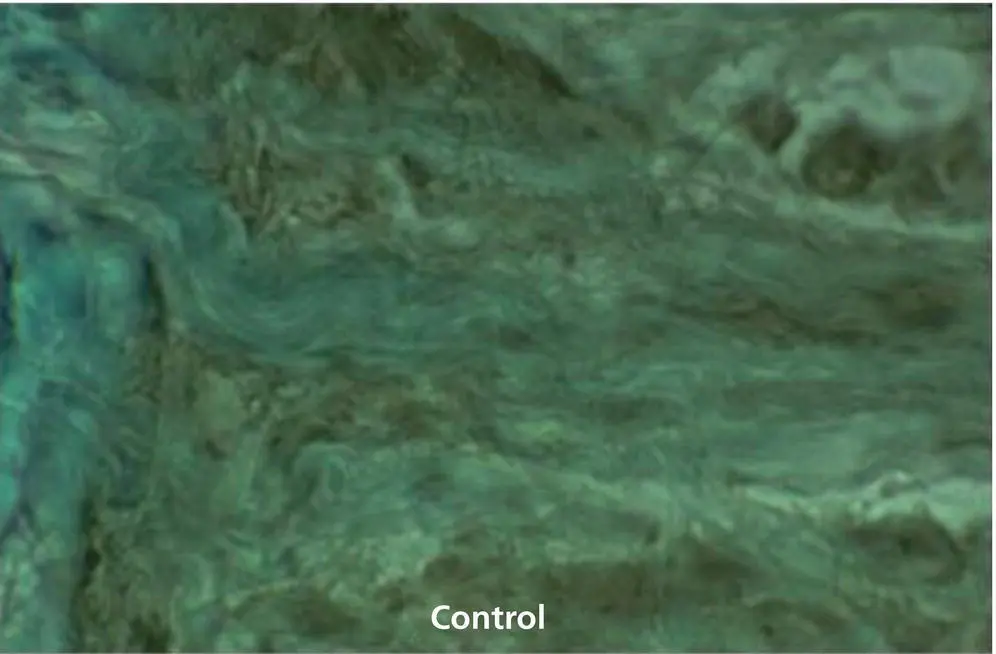

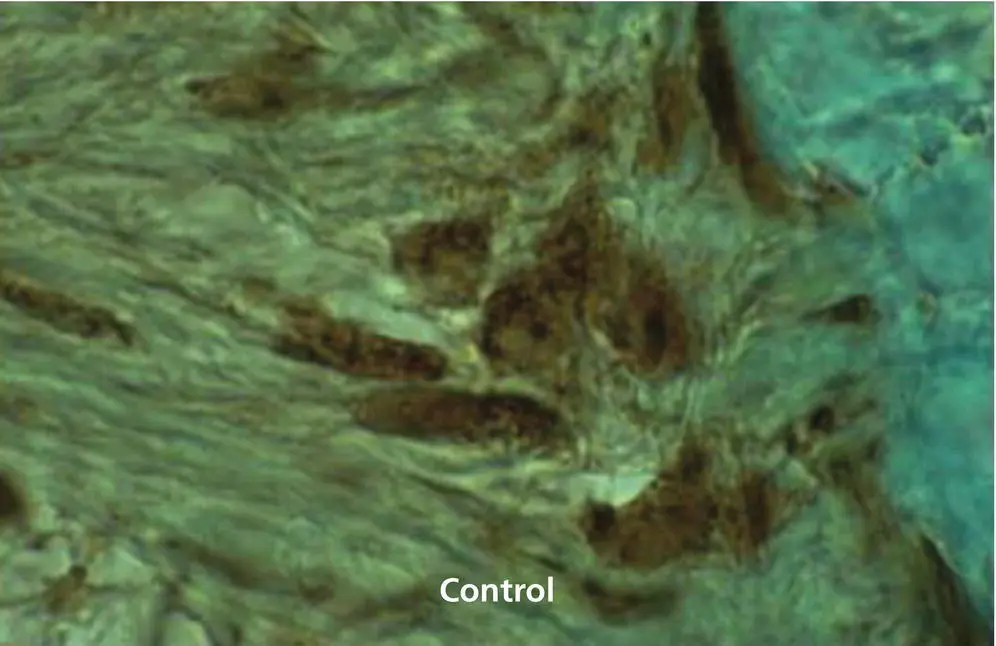

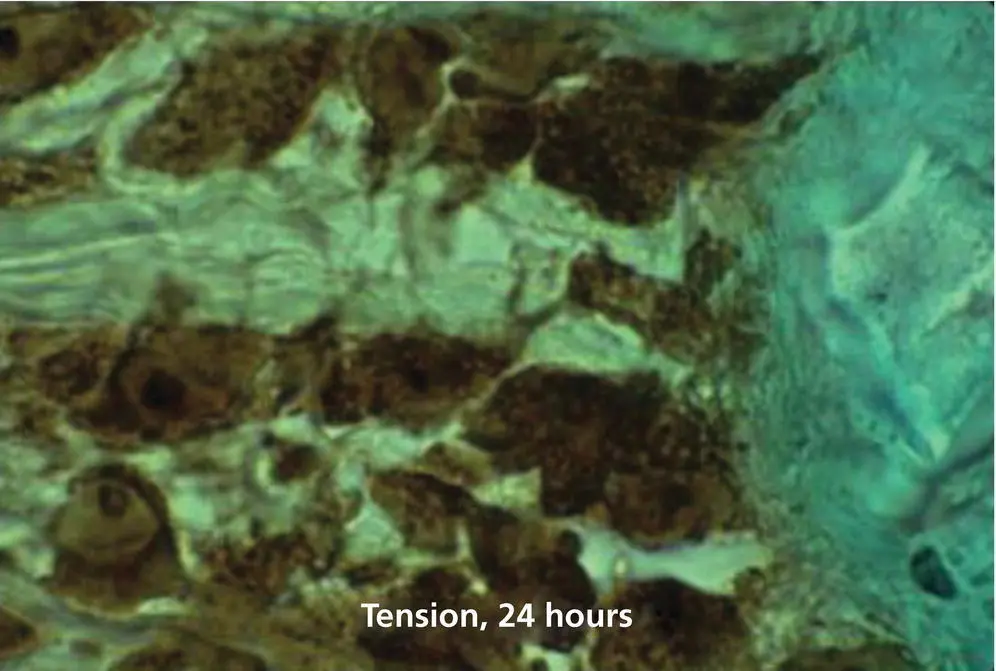

Identification of cellular and matrix changes in paradental tissues following the application of orthodontic forces led to histochemical studies aimed at elucidating enzymes that might participate in this remodeling process. In 1983, Lilja, Lindskog, and Hammarström reported on the detection of various enzymes in mechanically strained paradental tissues of rodents, including acid and alkaline phosphatases, β‐galactosidase, aryl transferase, and prostaglandin synthetase. Meikle et al . (1989) stretched rabbit coronal sutures in vitro, and recorded increases in the tissue concentrations of metalloproteinases, such as collagenase and elastase, and a concomitant decrease in the levels of tissue inhibitors of this class of enzymes. Davidovitch et al . (1976, 1978, 1980a, b, c, 1992, 1996) used immunohistochemistry to identify a variety of first and second messengers in cats’ mechanically stressed paradental tissues in vivo . These molecules included cyclic nucleotides, prostaglandins, neurotransmitters, cytokines, and growth factors. Computer‐aided measurements of cellular staining intensities revealed that paradental cells are very sensitive to the application of orthodontic forces, that this cellular response begins as soon as the tissues develop strain, and that these reactions encompass cells of the dental pulp, PDL, and alveolar bone marrow cavities. Figure 1.16shows a cat maxillary canine section, stained immunohistochemically for prostaglandin E 2(PGE 2), a 20‐carbon essential fatty acid, produced by many cell types and acting as a paracrine and autocrine. This canine was not treated orthodontically (control). The PDL and alveolar bone surface cells are stained lightly for PGE 2. In contrast, 24 hours after the application of force to the other maxillary canine, the stretched cells ( Figure 1.17) stain intensely for PGE 2. The staining intensity is indicative of the cellular concentration of the antigen in question. In the case of PGE 2, it is evident that orthodontic force stimulates the target cells to produce higher levels than usual of PGE 2. Likewise, these forces increase significantly the cellular concentrations of cyclic AMP, an intracellular second messenger (Figures ), and of the cytokine interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β), an inflammatory mediator, and a potent stimulator of bone resorption ( Figures 1.21and 1.22).

Figure 1.16 A 6 μm sagittal section of a cat maxilla, unfixed and nondemineralized, stained immunohistochemically for PGE 2. This section shows the PDL‐alveolar bone interface near one canine that received no orthodontic force (control). PDL and alveolar bone surface cells are stained lightly for PGE 2.

The era of cellular and molecular biology as major determinants of orthodontic treatment

A review of bone cell biology as related to OTM identified the osteoblasts as the cells that control both the resorptive and formative phases of the remodeling cycle (Sandy et al . 1993). A decade after this publication, Pavlin et al . (2001) and Gluhak‐Heinrich et al . (2003) highlighted the importance of osteocytes in the bone remodeling process. They showed that the expression of dentine matrix protein‐1 mRNA in osteocytes of the alveolar bone increased twofold as early as 6 hours after loading, at both sites of formation and resorption. Receptor studies have proven that these cells are targets for resorptive agents in bone, as well as for mechanical loads. Their response is reflected in fluctuations of prostaglandins, cyclic nucleotides, and inositol phosphates. It was, therefore, postulated that mechanically induced changes in cell shape produce a range of effects, mediated by adhesion molecules (integrins) and the cytoskeleton. In this fashion, mechanical forces can reach the cell nucleus directly, circumventing the dependence on enzymatic cascades in the cell membrane and the cytoplasm.

Figure 1.17 A 6 μm sagittal section of the same maxilla shown in Figure 1.16, but derived from the other canine that had been tipped distally for 24 hours by a coil spring generating 80 g of force. The PDL and alveolar bone‐surface cell in the site of PDL tension are stained intensely for PGE 2.

Figure 1.18 Immunohistochemical staining for cyclic AMP in a 6 μm sagittal section of a cat maxillary canine untreated by orthodontic forces (control). The PDL and alveolar bone surface cells stain mildly for this cyclic nucleotide.

Figure 1.19 Staining for cyclic AMP in a 6 μm sagittal section of a cat maxillary canine subjected for 24 hours to a distalizing force of 80 g. This section, which shows the PDL tension zone, was obtained from the antimere of the control tooth shown in Figure 1.18. The PDL and bone surface cells are stained intensely for cyclic AMP, particularly the nucleoli.

Читать дальше